A Monumental Life: Adam Heller's Stone Canvas

The Norfolk-based stone craftsman chisels stunning memorials and monumental art projects.

The Norfolk-based stone craftsman chisels stunning memorials and monumental art projects.

Adam Heller in his workshop

Everyone wants to be remembered. The Roman Emperor Nero (37-68 AD) had a 98-foot bronze statue built in his likeness. And so, history goes, with kings and queens and pharaohs, and even us “common people” the need to not be forgotten is what defines death and loss in our modern culture. Memorializing loved ones is, and always has been, more for the living than for the dead.

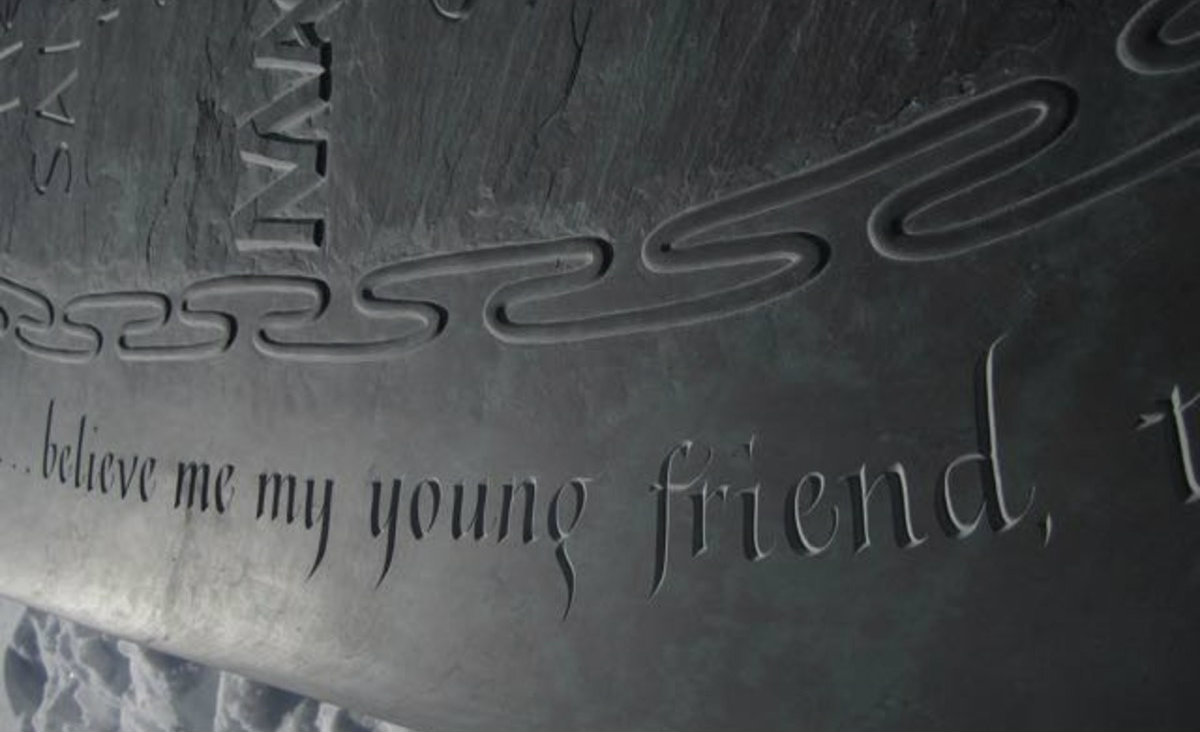

“I respect death. It is the great informer of all of our lives,” says Adam Heller, a Norfolk, Conn.-based stone carver. It is yet another gusty, chilly day, and Heller is trying to keep his 1850s barn (and studio) warm while he works; loading the small woodstove, boiling water for tea, all while patiently working a slab of black slate into a beautiful headstone for someone he’s never met.

“There is a lot of silence when I work,” says Heller. “It’s windy sometimes. I spend a lot of time moving the wood, bringing in water from the house to rub down the stones. All of that silence… and those physical tasks, they matter here.”

Heller’s life is, in some ways, monastic. Prior to having a family (and discovering stone as his artistic medium) some 20 years ago, Heller spent “a lot of time in the Himalayas” observing and living life in Tibetan monasteries. He also spent two years at the Benedictine Abbey of Regina Laudis in Bethlehem, Conn., studying under the Benedictine artist Sr. Praxedes Baxter. It was here that Heller says he first began hand carving stone (then later apprenticed with Nicholas Benson at the John Stevens Shop in Newport, Rhode Island).

“I am still really attracted to that kind of life, and to the idea that everything, even the most mundane task, has meaning,” he says.

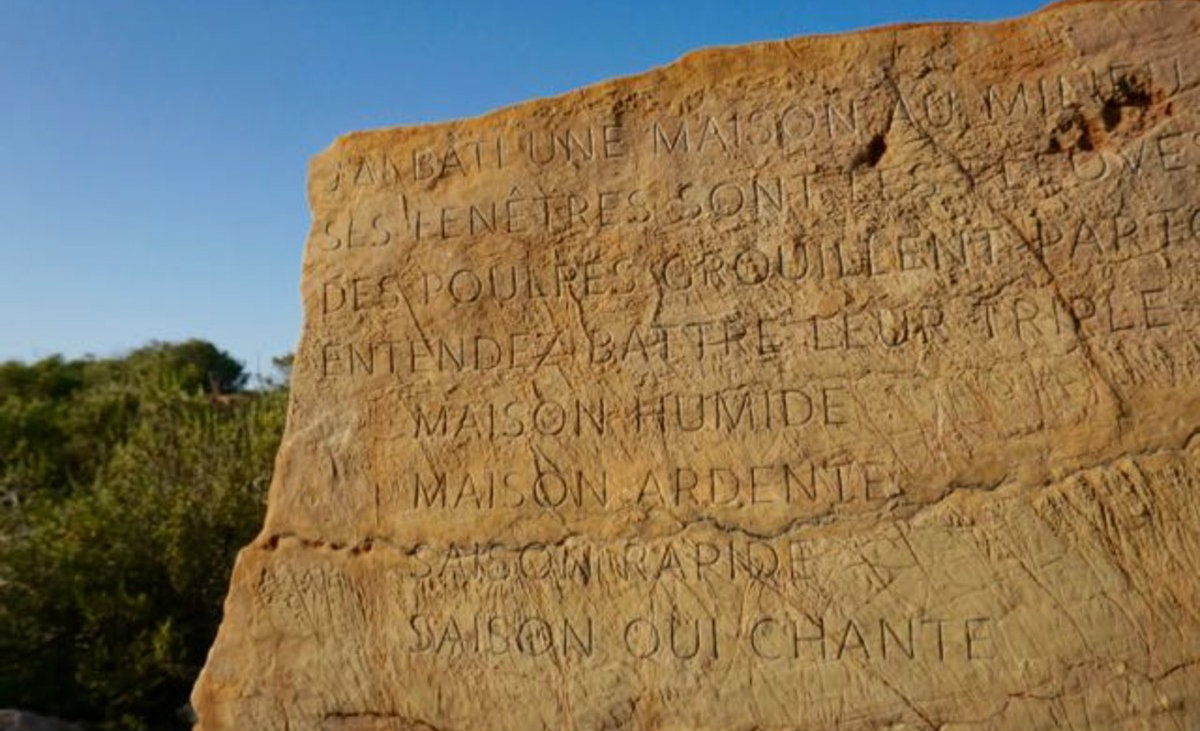

In addition to his work with memorial projects, Heller has also, quite literally, made monuments. Not the least of which were collaborative works with text artist Jenny Holzer. In 2012, Holzer Studio asked Heller for help “realizing a series of small limestone tables” Holzer had designed for a commission by the Whitney Museum of American Art (in NYC). A few years later, again with Holzer, Heller found himself working in Ibiza, Spain, on a site-specific, outdoor commission for art collector Guy Laliberté. Heller spent nearly two months there, chiseling selected poetry (in the classic Roman styling) on strategically chosen cliffs and boulders.

“It’s a beautiful, weird part of Spain,” says Heller. “We sited boulders off three islands in Ibiza and got to work on a small group of carvings. You start thinking in terms of decades and centuries when you do work like that.”

There is a brevity to Heller that is offset by his slender frame and wide blue eyes. He is grounded and calm and deliberate. Maybe because he must be; because the mere nature of his work forces him to be. When clients first approach—usually they find him online—Heller meets with them, preferably face-to-face. That meeting, for which Heller usually prepares coffee and tea and a tray of simple, nourishing victuals (cashews, dried apricots, cheeses), often takes up the span of an entire morning or afternoon. It is poignant, and their requests are often sad.

He has just finished some sketches of a headstone for a woman in her early 40s.

“It’s so final,” says Heller looking at the Roman lettering on brown paper.

Because of that finality, it can sometimes take years for a stone piece to be finished. Not necessarily because working with stone is a slow process — in fact Heller makes it look like cutting warm butter — but because clients cannot always make up their minds right away.

“Sometimes I start sketching while people are talking to me about their loved one,” says Heller. “From start to finish it can be a one- to two-year process. It’s a collaboration. I don’t really rush it. There is a real spiritual aspect to the whole process.”

Heller understands, and he is endlessly patient. Patient with his cat that walks all over the paper sketches in the barn studio, patient with his two children who still aren’t quite sure what their dad does for a living, patient with himself and the endless complexities of life, and death.

“We aren’t used to thinking this way, it’s not part of our ‘instant’ culture,” he says, blowing slate dust off a gravestone to reveal an intricate bird-branch design. “A little bit of my work is a pushback against that.”