The Art Of Vintage Lace And Va-Va-Voom In Millerton

Beata Gershon shares her love of Irish crochet lace at her shop and gallery, Beata Wearable Art.

Beata Gershon shares her love of Irish crochet lace at her shop and gallery, Beata Wearable Art.

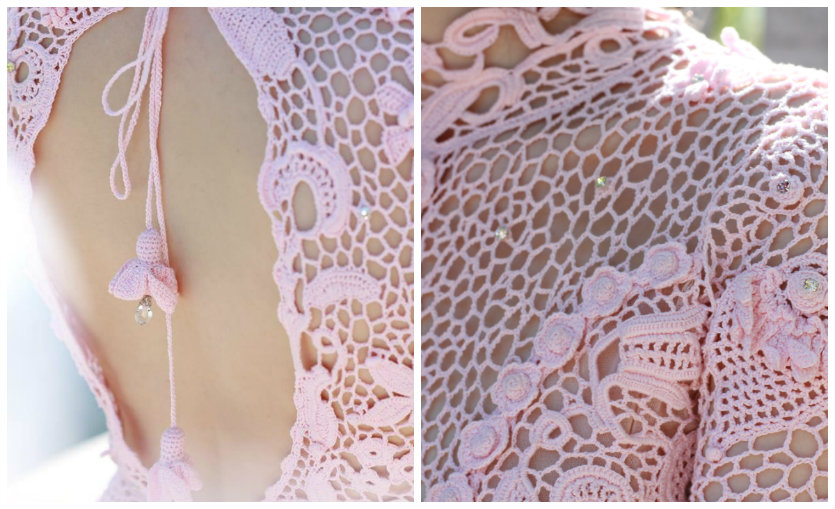

Closeup of Irish crochet lace

You don’t have to know about the history and art of Irish crochet to appreciate the exquisite nature of Beata Gershon’s lace garments. But once you learn a few facts, you may end up going down the Google rabbit hole, as I did, fascinated by the traditions, patterns, and high-level craft of Irish crochet lace. It becomes easy to understand how Gershon got caught up in the threaded webs that are woven into, as she calls it, wearable art. Vintage and new pieces created from her hands and from others around the world are on exhibit — and for sale — at Beata Wearable Art, her new shop in Millerton, New York.

“It’s my love, my passion,” Gershon says. Born and raised in Warsaw, she moved to New York after 9/11, and although one would assume she worked in the fashion industry, she was actually in real estate. But her mother had always sewed and crocheted, and Gershon did a bit of it, too. A few winters ago, she wanted a hobby, and came back to knitting and crocheting. By accident, she came across an old magazine that featured Irish crochet lace. Down the rabbit hole she went. Russian magazines (which she could read) offered decoded versions of the patterns. She found some videos and websites that helped her along, and she was off to the Irish laces.

A wee bit of background: The art dates back to the 19th-century famine in Ireland, where it was a way for women to make money. Motifs were made separately, tacked to paper, and the spaces filled in with mesh. Common motifs are roses and leaves, joined by delicate netting. It’s still done that way, and whether you come across an original vintage garment or one made today, the effect is timeless.

Closeup of another dress by Svetlana Pushkina

Gershon began to look for people who could make a garment for her, and found Svetlana Pushkina in St. Petersburg, who was making stunning pieces (witness the royal blue dress, modeled by Pushkina’s daughter). Most of the garments in Gershon’s collection come from her. Gershon also started collecting antique Irish lace, acquiring coats and dresses dating back to the late 1800s.

The garments are breathtaking, and inherently romantic. “They’re one-of-a kind, each one is unique, and will always hold their value if not destroyed and well-cared for,” Gershon says. “In my opinion, Irish crochet lace is a dying art that only a very few women are carrying on. In the future, these kinds of pieces will only be available in museums.”

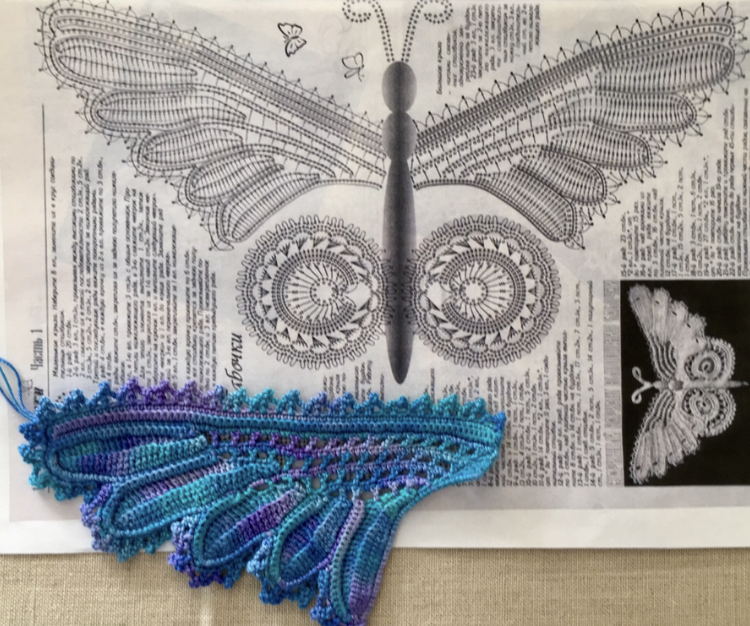

Gershon makes her own motifs; the blue butterfly was one she’d wanted to make but wasn’t able as a beginner to figure out the pattern from an antique pattern book. Later she found the schematics of the butterfly on Pinterest, taken from a Russian magazine dedicated to crochet. Later, she spied a garment on a Valentino runway show with a bigger butterfly motif, and found a woman in Bulgaria who made her something similar. That same woman made her a lavender top and skirt in a slightly different technique that leaves out much of the netting between motifs.

Along with her own motifs, Gershon has had collars made for her using 18th and 19th-century materials; these can be added to a top, sweater, or used as “statement jewelry.” Prices for her entire collection vary depending on the time and place the pieces were made. She’s also acquired some lace clothing made in China in the 80s and prices on those pieces are more accessible. If you’re the right size, a garment at Beata Wearable Art can be yours anywhere from $200 to $1500. It takes about three months to make each dress, just so you know.

When COVID hit, Gershon, who with her husband was a Millerton weekender, became a full-time resident. Her friend Basia Goldsmith, an artist (also from Poland, also living in Millerton) was looking for a place to paint and store her work. She suggested they rent a space together on Center Street. The shop is open three days a week for now, and Gershon has been busy creating her website and lining up her social media. She has many more pieces that still have to be photographed and is waiting for when it’s safe to do a fashion shoot.

Passersby have stopped in and expressed interest in the garments, but there’s only one of each made in one size, so it’s really more of a private collection. But Gershon is fine with that. “The amount of work put into it will never give you enough return to make these pieces your source of income,” she says. “I am absolutely in love with my wearable art and would like to share my passion with the world around me.”