AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Mark writes.

In winter it sometimes seems to us that our main function is simply to serve as movers of a mountain of hay. Farmers who raise grazing animals often describe themselves as really grass farmers, whose main challenge is to raise the right mix and quality of grasses, legumes (like alfalfa and clover) and forbs (broad leafed flowering plants, mostly regarded as weeds) for their herbivorous herds to eat. Cows and sheep are both ruminants, part of a broad class of animals — including goats, deer, moose, elk, and many others — which can actually digest these forage crops and indeed thrive on them.

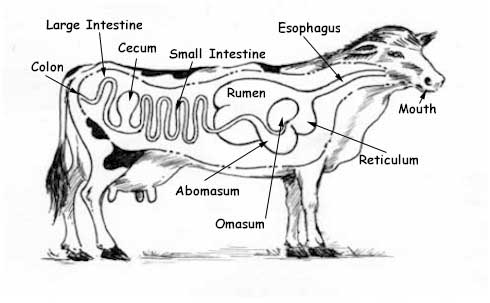

Ruminants can digest grasses because they have a complex four-part stomach in which the largest chamber, the rumen (in a mature sheep it can hold up to ten gallons), takes in roughly chewed forage and, operating like a fermentation vat, stores it, sets various micro-organisms to work breaking it down, then regurgitates it for the animal to chew on. After further chewing, the clump of food is reswallowed, passed back through the rumen and its antechamber, the reticulum, and finally, when it is sufficiently fermented, passed on through a third chamber, the omasum, to the the true stomach, the abomasum, where enzymes and acids similar to those in a human stomach complete the digestive process. The process of chewing the regurgitated forage is known as "chewing the cud," and it takes place daily as the animal lies on the ground, relaxing. "Monogastric" creatures like humans and pigs, relying on just a single stomach and taking no particular pleasure in chewing the regurgitated cud, cannot digest grasses. Instead, we rely on ruminants to give us access to the nutrients in these forage crops by transforming them into meat for our table.

Different animals prefer and thrive on different mixes of pasture vegetation. Cows can generally thrive on grasses, the least nutritious of these forage plants. For sheep, the preferred forage is forbs with their higher nutritional value. In between those two on the nutritional scale are the legumes with their high protein content. At one time, before we became directly engaged in farming, we assumed that pastures consisted of whatever grasses naturally came up. We’ve since learned that a pasture is really a crop — a deliberate mix of grasses, legumes, and forbs that requires seeding, fertilizing, and even weeding. From May to October, fortunately for us, the animals can graze this mixture themselves out on pasture, and the main task is directing them to the locations where we want them to be grazing. In winter, we’ve got to bring the pasture to them, in a preserved form, the miraculous class of products I’ll refer to under the general category of hay. Hay is pasture forage that has been cut, sun-cured, baled, and stored in a dry place. But these days there is a whole other category of forage that is encased in plastic, and allowed to ferment into a moist delectation called "baleage." This is a modern variation on the fermented forage that used to be created in silos and was called, appropriately, silage. We buy a couple dozen large bales of baleage from a farm in Ancram for the cows, who like it and can tolerate it, but must keep it away from the sheep, who will develop digestive problems if they eat it. The cows must groove a bit on the alcoholic content of this form of hay. Our life would, perhaps, be simpler if we could produce our own hay. But we don’t have the acreage to both graze our sheep and cows through the summer and also produce sufficient hay for winter. And we lack the necessary equipment and a place to store a huge amount of hay even if we were we able to produce it. So we buy hay for our herbivores throughout the winter, incrementally getting in as much as we can store at a time.

Though we don't eat the hay and have rarely been tempted to do so (except when a particularly sweet bale arrives), we have by now become something of hay connoisseurs. What's else is there to know about hay? Aside from the difference between the fermented and dried options, there are also different baling styles with different implications for storage and handling. Hay may be made into small square bales that weigh perhaps 15 or 20 pounds, or rolled into larger bales of several hundred pounds, or compressed into humongous rectangular bales, which is how we're mostly buying it these days. These bales are huge, about 6 feet by 3 feet by 3 feet, and weigh 800 pounds. Our small pickup truck can transport just one of these bales at a time, and only by putting down the tail gate and letting the bale hang over the back of the truck bed.

And then there’s the all-important variation in quality.The chief quality differentiation from any given pasture is the distinction between "first cut," usually harvested in our region in May or early June, and "second cut" from later in the summer. The second cut is less dried out, more delectable, and almost always more expensive. But weather conditions can also affect quality. And there is the particular mix of grasses, legumes, and forbs. And how well has it been stored? Is the bale full of wide ribbons of still greenish grass or is it stalky and almost as stiff as straw? There’s hay with a strong sweet aroma that transports you back to summer and hay that has little or no odor at all. We can pretty much tell, when opening up a bale, how enthusiastic the animals will be about it based on these various characteristics. And amazingly the characteristics that appeal to the animals appeal also to us. The sweet smell of greenish ribbons of grass is enough to release those happy taste hormones in my brain.

Having a barn full of hay gives me a nice contented feeling too, knowing that the main ingredient in keeping our sheep and cows fat and happy is on hand and only needs moving about. Keeping stocked in winter is its own challenge and does require constant attention to conditions. If it's going to be in the 40s, it could be too muddy for the delivery truck to get near the barn without getting stuck. If it's going to rain or snow, we can't take delivery because the hay will get wet and potentially rot or grow dangerous mold or fungus. If we wait til after a big snow, we'll have to plow for access, increasing the cost of the hay for us. Last Monday morning looked to me like the perfect time for a major hay delivery from Stone House Farms, which supplies us with the huge square bales. I arranged for delivery of four of them, a total of 3200 lbs. Through a major miscalculation on my part, however, I found myself the only one around to take apart the bales and carefully stack the slices of compressed hay into the barn. It took me 90 minutes, working alone, to fill the barn's four storage stalls to the rafters. And I finished loading in just as the snow began to fall heavily. I was amazed to have managed that, and chores, and still make the 11:51 from Rhinecliff to Penn Station to, slightly belatedly, start my week of work in the office. But it was an immensely satisfying feeling to be fully stocked with hay, and to know that the beef cattle scheduled to go to market in just two weeks will do so in a state of well-fed contentment.