AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Mark writes.

The momentous news on the farm this week is that Roxie the cow gave birth to a sweet, petite heifer calf on Friday morning. Nearly a week earlier I had become convinced that the birth was imminent, based on a variety of observations: that Roxie’s udder had blown up to the size of a beach ball, practically dragging the ground; that she seemed as wide as a house; that she was lying uncomfortably a lot of the time and standing off by herself a bit. And that this most feisty of cows, who has nobody’s favorite personality and who seems more unpredictable and aggressive than our bull, Titan, was suddenly docile and pliant. When I walked up to stroke the side of her face, she willingly accepted the attention rather than, as she usually does, butting her head to drive me off. My pronouncement that the birth was imminent raised expectations all around. Peter and I spent a great deal of time tracking Roxie’s movements and looking for signs of labor. Wednesday Peter observed Roxie going down into the woods at the bottom of the pasture, alone, and grew concerned that perhaps she was feeling ill because of trouble calving. Whenever Peter and I spoke, Roxie was the first order of business.

Thursday at midday, Peter, fearing that Roxie (at right) was carrying a dead calf, phoned our cow-savvy neighbor, Jordan Kukon (who has been helping birth cows since childhood on his family's dairy farm) to come over and examine her. Jordan easily drove Roxie into the corral, but getting her into the narrow chute where she could be locked in and examined turned out to be another matter. In the process, Jordan was almost knocked over, Kyle was butted up against the corral fencing, and Peter nearly trampled when Roxie smashed through the side wall of the chute and escaped. But not before Jordan managed to probe her enough to determine that the calf had moved down and appeared to be alive. His advice was to wait and see. Good advice, as it turned out. Trooping out early in the morning to start chores on Friday, Peter and Kyle were pleased to discover that Roxie's calf, a tiny, snowy white female with black ears and kohl lined eyes, had been born. Her arrival induced not only a great sense of relief but also a sense of well-being and even prosperity. Although the calf may have started small, one can be sure that a year from now she’ll weigh more than 500 pounds and, ultimately, that she may tip the scale at close to a half ton.

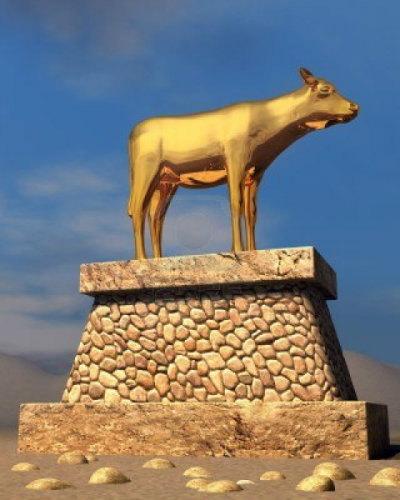

It is easy to understand why cows are so associated with wealth and comfort. Remember the story of the Exodus from Egypt, which Jews retell each year at this time (Passover), that a golden calf was the false god the Israelites worshiped while Moses was up on Mt. Sinai. And recall that one of the devastating plagues visited on the Egyptians in order to induce their release from slavery was, according to the Haggadah , “murrai," which is, as Wikipedia states, “an umbrella term for a number of different diseases, including Rinderpest, erysipelas, foot-and-mouth disease, anthrax, and streptococcus infections" that kill cattle and other livestock. At this period, the welfare of livestock was synonymous with the welfare of the group. Given how central the welfare of our cattle may be to the economic success of our farm, I have spent a fair amount of time thinking about whether there’s a better way for us to manage them. Roxie arrived here as a two-year-old, so I don’t feel responsible for her personality. I don’t blame her mother, Alicia, either. Alicia and Roxie arrived together, and Alicia is perfectly docile, friendly, and manageable. But Roxie’s almost ceaseless resistance to us has led me to speculate about whether we could have done something to induce in her a friendlier, more cooperative disposition. In considering the question, I was surprised to find myself thinking back to a classic work of ethnography, The Nuer, by E.E. Evans-Pritchard, which left a major impression on me in college. The author studied the Nuer tribal group in the far reaches of the Sudanese Upper Nile in the early 1930s and it’s hard to imagine a people more dependent on their cattle. As Evans-Pritchard described it, the Nuers' diet was almost entirely cattle-derived — principally milk (which they used alone or in a porridge with their staple grain, millet), but also soured milk kept in gourds, and cheese made using not only the cow’s milk but also its urine. They even let the cows' blood occasionally to use as a dietary supplement. The Nuer valued cattle for their meat, too, although they usually did not obtain it through deliberate slaughter but rather when the cattle died a natural death. As one informant described it, at a cow’s death “the eyes and heart are sad, but the teeth and stomach are glad."

The Nuer were also dependent on various parts of the cow for their clothing and household implements. Cow dung was gathered as fuel and for use in plastering the outside of domestic structures. Dung ash was used in food preservation and as a white powder for ritual use on the human body. The cows were the Nuer’s chief repository of wealth, and the Nuer lived in small encampments with their livestock kept closely among them. As Evans-Pritchard’s comments, “It has been remarked that the Nuer might be called parasites of the cow, but it might be said with equal force that the cow is a parasite of the Nuer, whose lives are spent in ensuring its welfare. They build byres, kindle fires, and clean kraals for its comfort; move from villages to camps, from camp to camp, and from camps back to villages for its health; defy wild beasts for its protection; and fashion ornaments for its adornment. It lives its gentle, indolent, sluggish life thanks to the Nuer’s devotion. In truth the relationship is symbiotic; cattle and man sustain life by their reciprocal services to one another." A corollary (we can’t say if it’s actually the result) of this assiduous devotion to the herd’s welfare was, as Evans-Pritchard describes it, incredibly docile cattle. The Nuer then typically lived their lives barefoot and naked, and they could be perfectly comfortable and safe among their cows in that unprotected state, gently directing the movements of the herd. Evans-Pritchard saw this as living proof of how primitive the Nuer were. But to me it also says something about the tribe's recognition of the cows' value to them and an intelligent decision to devote themselves to effectively fostering that value. The reason the cows are so responsive to human needs and direction is that such unstinting attention and effort has gone into their comfort and well-being. A cow would not be so stupid as to defy or harm the source of her welfare. Well, dear readers, don't expect to arrive at the farm to find Peter and me naked but for a few strands of beads. However, we may take at least a page out of the Nuer book and do more to establish a personal "best friend" relationship with our cattle — in particular the irascible Roxie. Oh God, give us the time and energy to do so.