AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Mark writes.

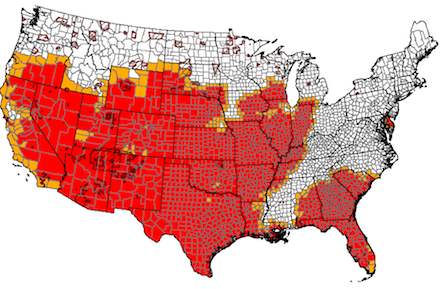

You can't call the rain abundant this summer, but at least in recent weeks we've gotten enough to keep us off the drought disaster area map on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) website that has close to two thirds of the American land mass painted bright red. The widespread effects of this American drought have become a dominant news story in recent weeks. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization is warning countries that produce agricultural commodities not to restrict exports, which would violate commitments major producer countries, like the United States, have made in the past. We are told that world commodity prices will likely rise 6% this year, and that the drought is going to intensify the food security crisis poor people have experienced in this country since the recession hit. Some have suggested that we reduce ethanol production to make more of our scarce corn available for food. The USDA drought map includes the Southeast, the corn belt, the plains states, the mountainous West, and a good chunk of the far West. When I look at the green of our vegetable garden — which may not be lush but is getting along adequately with daily irrigation — or see the overflowing bins of produce at various farmers' markets in the region and in New York City, I feel far removed from all that, and grateful to live in the Northeast. Don't these images mean that we who live in this region, particularly those of us locavores who eat grass-fed meat and produce and dairy from the neighborhood, can just breathe a great sigh of relief and feel self-satisfiedly insulated from this great disaster?

I'm sorry to tell you that the answer is no. Your food prices are about to go up, even if you buy from the likes of us small local producers. No matter what we do, we are part of the national market and are therefore affected by the drought. As Peter pointed out in a previous post, no farm is an island. The way this works was graphically illustrated to me when I made my weekly trip to the local farm, Saulpaugh's in Livingston, NY, where I buy whole oats and a corn-soy mix for our breeding pigs, cracked corn and another mix for our egg-laying chickens, and grain treats for our sheep. At Saulpaugh's last week, all the prices had gone up, roughly 10%, for the second time since Spring. (The organic feed we buy from Lightning Tree Farm in Millbrook for all the turkeys, geese, chickens, ducks, and pigs we raise for consumption comes in much larger quantities and less frequent deliveries, so we have not yet felt the effect there but it is all too predictable.)

I asked why the price rise, and the answer was pretty simple. Saulpaugh's not only grows its own grains but also relies on other local farmers to keep them supplied. And those other local farmers had suddenly raised their prices because of the solicitations they were getting from big national distribution companies (ADM — Archer Daniels Midland — was the name particularly mentioned) to buy their grains at dramatically higher prices. There is a desperate need to replace the huge commodity farm production in the corn belt that's been devastated by the drought, and firms like ADM are out there sucking up grain from producers wherever they can get it and paying an excellent market price. It is apparently quite unusual for the solicitation to go in this direction. In normal times, it seems, farmers bring their grain to these big distribution companies as markets of last resort, when they can't dispose of their production locally. Now with the companies soliciting them, the tables are turned, and it is only worthwhile for them to sell locally if the local sales match the national market price being paid by ADM. This means our local producers are, in effect, producing for the national market, and we who buy from them locally are, in effect, competing with buyers from all over the country. In market terms, the drought may as well be here, even though it's pouring outside as I write this.

It's easy to become alarmed when the television news shows pictures of shriveled corn stalks and maps screaming bright red. To try to calm some of that alarm and provide some perspective, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, in an interview I heard Thursday on Marketplace, explained that there may not be that great an effect on food prices when commodity prices go up: "The farmer… in the United States, only gets 14 cents of every food dollar that's spent in the grocery store. So when commodity prices go up, … [even if] they… go up dramatically,… the impact on food prices is very, very marginal. We would expect to see somewhere between a half a percent to a percent increase in food inflation as a result…of the drought." What Secretary Vilsack says may be true for those who buy highly processed, packaged, industrial foods like breakfast cereals, where the cost of the real food in the box is dwarfed by the cost of the processing and by the cost of the box itself and the advertising that went into making you want it. Unfortunately, it's not so true if you eat real food, in its commodity form, like eggs and meat. These prices will rise. We kept our egg prices steady the last three times the price of our layers' food went up. The last time, I calculated that we could still do better than break even if we sold our entire weekly production, and it has been no problem to do so. This time, the feed prices leave us in the red even if the hens produce abundantly and we sell everything, so our egg prices will go from $3 a dozen to $4 effective immediately.

For our fall and winter meat production, the impact on us will be felt more slowly and we will be more gradual about raising the price. But please note: the prices will rise. One lesson that we will re-learn in this crisis is that we live in the larger world and can never fully insulate ourselves from its problems. Perhaps this is why last week I was so taken with a whimsical yet spiritual sculpture called Rain Totem, dedicated by its artist, Robin Tost, to the wish that we be spared a drought this summer. Ann Jon, curator of SculptureNow’s wonderful exhibit on the main street of Lenox, Massachusetts, showed us this piece last week, and its image remained in my mind since then. So much so that I've decided I will buy it this weekend, and bring it to the farm to preside over the gardens. We may not need the Rain Totem right now, but the rest of the country sure does. —Mark Scherzer