AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Mark writes.

In the last couple of weeks a few late lambs have arrived, and the most recent, the 27th of the season, born February 5, was initially struggling. His mother did not seem to be producing much milk and the little ramling did not seem to be working at getting it. He seemed so weak at first that Peter thought he would not make it without supplementing his mother’s milk. Finding our powdered milk replacer spoiled, he rushed off to Tractor Supply for a new bag and returned to find the situation not quite so dire but gave the lamb a little bottle boost anyway. The ewe's milk production soon improved considerably. By the second day, the little one seemed to have stabilized. But then when I arrived for the weekend on day three we noticed yellow goopy stuff on his back legs and tail — it was “scours," the term sheep people use for diarrhea. In young lambs scours is often not just a minor period of upset but can become life-threatening as the lambs quickly dehydrate. As is our wont, we did not reach for antibiotics or other medications. Instead, Peter checked our various reference books to see if there were any special remedies for lambs this young. Oddly, our voluminous veterinary medicine handbook had remedies for diarrhea in a veritable Noah’s Ark of animals, including ostriches, but nothing about sheep or lambs.

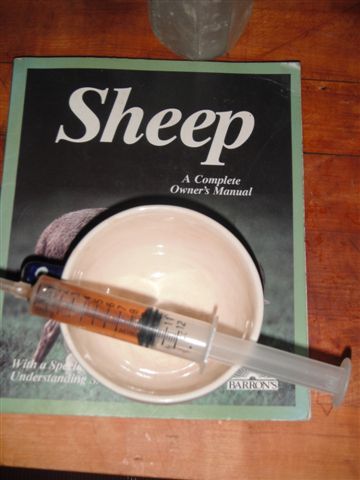

Our specialized sheep reference works recommended tea to treat the condition. But Peter was convinced, based on his experience with our ewe Sultana (who we had to bottle feed and nurse through numerous bouts of scours in her first months) that yogurt is also very helpful. Taking no chances, he made a cup of tea and dished out a cup of yogurt, set them out for me with little (plunger type) syringes, and instructed me to administer both. What Dr. Peter dictates, Nurse Mark carries out. Saturday at evening chores I grabbed the three-day-old ramling, held him tight to me in a kind of headlock, opened his mouth and slowly squirted in the tea from the side. He readily took it and then I did the same with the yogurt. He was considerably less enthusiastic about that, swallowing what I got far enough back in his mouth but letting dribble out what was near the front. The next morning I was amazed to find results that seemed no less than miraculous. His back was clean. There was no sign that there had been any problem since the night before. I repeated the doses just to be on the safe side, but immediately thereafter released him and his impatient mother from their birthing pen to rejoin the herd. Monday, our farmhand Kyle, who is incredibly attentive to the state of the animals, reported that the tiny lamb was already frisking with the other two lambs close to his age, and that he seemed absolutely normal. We of course continue to monitor him, but it’s a great relief to know that such simple home remedies as tea and yogurt and a certain amount of sympathy can be such life savers.

I was reminded of this experience later in the week when I read two articles. One, by Maryn McKenna from an online publication called Wired, was about antibiotic use in animals. She reports on the recent release of two documents by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration with the rather daunting titles: "The 2011 Retail Meat Report from the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System" (“NARMS”) and "The 2011 Summary Report on Antimicrobials Sold or Distributed for Use in Food-Producing Animals."broad totals of antibiotics sold in various categories for livestock consumption. The second document reports broad totals of antibiotics sold in various categories for livestock consumption, and reveals that in 2011 the amounts sold in the U.S. were 29.85 million pounds, a significant increase over 2010, and an approximately one-million pound increase over 2009. In fact, the amounts sold have steadily increased since 2003. The quantity of antibiotics sold for farm animals is four times the amount sold for human consumption. Sales for human consumption have been stable over the last decade. The increase in use of antibiotics on farm livestock has come despite repeated warnings about the dangers of over-use.

McKenna concludes that the increase in sales is particularly worrisome because the FDA, which is charged with protecting the integrity of our national food supply as well as insuring drug safety, has recently abandoned its attempts to use regulations to restrict routine over-use of animal antibiotics, and has gone over to a "voluntary approach." With a so-called "voluntary approach," can there be any doubt that animal antibiotic use will increase even more, resulting in the evolution of antibiotic resistant bacteria that will pose grave risks to human health? Corroborating the concern about resistant bacteria, the NARMS report contains even more bad news. Salmonella isolated from nearly 45% of commercial chicken samples and from 50% of commercial ground turkey samples were found to be resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics. In smaller but still significant samples of these meats, the salmonella was found to be resistant to five or six classes of antibiotics.

The other article that caught my eye was a New York Times report on a Scandinavian scientific study. Fish exposed to low levels of anti-anxiety drugs, simply through swimming in water that receives residues excreted by humans into the environment, have been found to experience observable changes in behavior, becoming less social, eating faster, and becoming more active. The environmental consequences of these changes in fish behavior are not yet known, but we can certainly assume that there will be ecosystem changes as a result. Industrial agriculture routinely gives antibiotics to animals, not necessarily to treat disease but to proactively prevent it and to accelerate weight gain. The immediate economic payoff is, of course, enjoyed by the agribusinesses engaged in this practice. But the long-range negative consequences, some of them as yet unknown, are going to be borne by all of us. It is easy to understand the temptation to use these drugs. Modern science gives us powerful tools to seem to beat all variety of illness, discomfort, depression or anxiety. And we see otherwise rational consumers demanding antibiotics at the first sign of a sniffle, or unhesitatingly taking psychotropic medications to alleviate even minor bouts of depression or anxiety they could live with. What we're increasingly learning is that manipulating our environment to achieve utopia may be short-sighted by ignoring because we are ignoring the long-term costs and side effects. Peter and I continue to monitor our animals carefully to assess their well-being, and intend to continue medicating them only when necessary and after trying more benign remedies. And the same will continue to go for my personal health care — making tea, yogurt, and talk my preferred remedies for colds, anxieties, depression, and hoping that, like the lamb, I will continue frisking around just fine.