AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Mark writes.

As we continuously tell you, we are in lambing season. It started in earnest at the beginning of December and still hasn't stopped. The two dozen births we've had so far have gone smoothly, on the whole. One lamb, Sultana's, unfortunately never could stand, and died quietly the night he was born.One ewe, Kose, successfully gave birth to healthy twins but she herself had edema, her swollen neck signifying a parasitic infection. To her great dismay we kept her confined with her lambs and a rotating cast of other birthing ewes for six days while we administered daily medication to her. And one young ramling, born to Theresa (on whom I bestowed that name because her tag number is 57, and both that number and the name Theresa are easily associated in my mind with Heinz and its 57 varieties) has testicles that still haven't descended four weeks after birth and some diarrhea. But all in all, the glitches have been quite manageable.

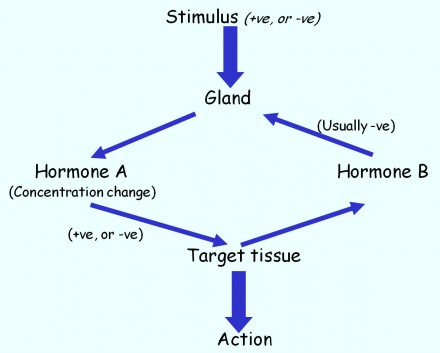

We like to think that by now we understand our sheep and their behaviors and instincts pretty well. But the book I just finished reading, The Chemistry Between Us, has given me entirely new insights into the dynamics of sheep family life. We have, for example, long assumed that the reason our birthing ewes, who are after all herbivores, eat the placenta of their lambs was their need for nutrients after the exhaustion of giving birth. That may well be a factor, but according to this book the fundamental purpose served by that act is to assist with ewe-lamb bonding. Although the ewe recognizes the lamb's face, she primarily operates on her sense of smell, and it is by licking her lamb clean and eating its placenta that the particular smell of her lamb becomes embedded in her sensory system. The smell of the lamb causes the release of oxytocin, a hormone in the ewe's brain, which helps prime the amygdala, part of the brain, to induce loving maternal behavior by the ewe. Nursing, too, through neurons that transmit messages from the nipples to the brain, causes the release of oxytocin in both the body and the brain. In all mammals, indeed throughout the animal kingdom, oxytocin promotes parental caring, among other instincts.

One of the wonderful things about this book is that it demonstrates persuasively (through numerous animal and human studies) that such needs and urges as sexual desire, love, and territorial aggression are closely tied to biochemical processes. Levels of hormones and other substances in the body, and even differences in particular strands of DNA, seem to determine personality types and exert strong influence on actions that we tend to think of as the products of our will. The biologically driven element in sexual attraction, love, altruism, and aggression puts much of it beyond rational control and hard to subject to moral judgment. Take homosexuality, for instance. There are, according to this book, gay rams. We've never to our knowledge had one, but then we castrate almost all of our ramlings and the resulting wethers seem not to have much sexual interest at all. Intact gay rams that can and do function sexually but don't mount ewes are apparently referred to by farmers as "nonworkers." These rams are fully male in their behavior. Unlike ewes in heat, who urinate to attract males with their scent, then stand still, waft their tails, and glance back over their shoulders toward the ram with a come-hither look, gay rams sniff, kick, lick, and vocalize like other rams to seduce the objects of their desire. The difference is, the object of these rams' desires are other rams, whose presence triggers the release of sex inducing hormones in the gay rams. As far as we know, these rams do not differ from other rams in that they had distant fathers. All rams have distant fathers. They do not appear to have been raised in different cultural or moral environments from straight rams. The scientists studying these gay rams theorize that there is something in the organization of their brains, perhaps due to particular environmental influences at particular points in fetal development, that causes this variation in their orientation. This may have implications for understanding human sexual orientation as well. My favorite nugget of information in this book was one that does have more direct relevance to our farm. We have three sheep who we raised as bottle fed lambs: Orhan, Sultana, and Nilufer II. We have to bottle feed if the mother dies (as was the case with Nilufer II), or has insufficient milk (as with Orhan), or rejects her lamb for some reason (Sultana). We cherish the unusually close bond we develop with our bottle babies (they are more like pets than livestock), but would prefer to avoid having to bottle feed more lambs because it requires six feedings a day, including the middle of the night, with heated formula, whether they're in the mud room or the barn. The formula is quite expensive, and the feeding goes on for weeks. It seems, however, that there is another option, developed by an anonymous shepherd or shepherds in times long past, but studied more recently by scientists at the University of Cambridge. One can trick a nursing ewe into adopting an orphan lamb by stimulating her vagina and cervix as happens in sexual activity or giving birth. If one does that and immediately places the strange lamb in front of her, she will bestow the maternal favor of allowing the new lamb to nurse on her rather than kicking the strange creature away.

We will not speculate how the original discovery of this phenomenon occurred to that long ago shepherd. The scientists at Cambridge accomplished the desired state with five minutes of cervical and vaginal stimulation using a very large dildo. Other scientists have since replicated the results with goats and horses, using hands and laboratory tools, among other things, as stimulators. It seems that the kind of major stimulation of the cervix and vagina that happens during natural childbirth in humans, and lambing in ewes, releases a flood of oxytocin in the brain and thus causes the major bonding that occurs between mother and offspring. A study of human mothers who gave birth by C-section confirms this understanding of the physiology, in that on average the C-section mothers proved less responsive to their own babies' cries than vaginal birth mothers. I mentioned these findings about vaginal stimulation to Peter and suggested that next time we find ourselves with an orphan lamb we buy a large dildo, do the vaginal-cervical stimulation and save a fortune on formula. Perhaps mindful of stories about farm boys, and always with an eye to saving money, Peter replied, "Why go to the expense of buying a dildo?"