AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Peter writes. Our fava beans, spinach, lettuces, cabbages, and swiss chard have germinated, and many other seeds are planted and not far behind. The earliest spring greens are coming in—a time that often triggers a reverie of one kind or another. I usually enjoy writing about greens with a curious history or mythology. For instance, vegetables associated with the antics of the Greek gods that have played a role in mytho-historic droughts, famines, and disasters, or that have come to us as a result of strange doings in the Garden of Eden. It’s not the goody-goody vegetables that grab my attention, but those that are reputed to act as amulets against evil, that are believed to ward off diseases, and that serve as aphrodisiacs—or, in some cases, cause madness—that tend to fascinate me.

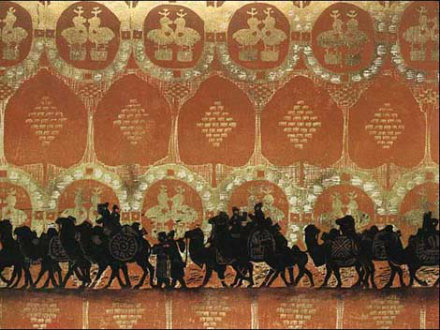

Homely spinach is not one of these. Despite its ancient history (originating in Persia, spinach spread eastward by Arab traders to India, Nepal, and China, while also spreading westward by the Saracens to Sicily, Spain, France, and Britain) self-effacing spinach seems to have never taken on the associations and beliefs that have accrued to other more flamboyant vegetables. Spinach probably reached China in 647 AD and Sicily in 827 AD, finally appearing in France and England in the 14th century. Apart from certain Arab medical and agronomical treatises in the 10th and 11th centuries, spinach doesn't seem to have gotten much press. While it's true that the great Arab agronomist Ibn al-‘Awwam did in the twelfth century (by which time spinach had reached Spain) proclaim it the “captain of leafy greens," it's an accolade that's, sad to say, nothing to write home about.

Perhaps its most significant moment of historical recognition, the apotheosis of spinach so to speak, came in 1533 when Catherine de Medici became Queen of France. It's reputed that she so fancied spinach she insisted on having it served at every meal. What the French court thought of her passion is not known. But her influence continues to the present, as any dish including spinach, in honor of Catherine’s origins in Florence, is described as “Florentine." Strangely enough, it wasn't until the appearance of Popeye the Sailor Man in the 1920s that spinach took on mythic significance. While spinach didn't gain recognition as the food of the gods, it did achieve a kind of American fame as the food that fueled the exploits of a comic everyman kind of superhero. This myth was apparently the outgrowth of another myth: that it had ten times its actual iron content. The story, also apocryphal, was that in the 1870s a German scientist, Emil von Wolf, misplaced a decimal point when measuring spinach's nutritional value. Hence, those exploding cans that gave Popeye his great power in times of need.

While not living up to popular belief, spinach is actually very rich in iron. In comparison to most foods, it's extremely nutritious and high in antioxidants and folic acid. It also has high calcium content, so when Popeye popped those cans and chugalugged them down, he was not only receiving an energy boost but taking in food values that protected him from various potential illnesses. But as rich as spinach is in food value, its values are easily dissipated since it loses many of them after being stored for little more than several days. Given the length of time that most of our supermarket vegetables spend in transit and being artificially “freshened" by mists in the cooled produce section, the likelihood of the food values of spinach surviving are remote. The message is: grow your own spinach or get it directly from the grower. But even if you do this, the food values of spinach are also easily lost in cooking. Best, obviously, is to enjoy it raw in salads or boiled or sautéed very lightly. In addition to positive values, spinach also carries certain dangers, as it's one of the most pesticide-retentive vegetables on the market. It's one vegetable, therefore, that it makes sense to buy organic. It was neither Catherine de Medici nor Popeye who converted me to spinach, but as with so many foods, it was my time living in Turkey that opened my eyes to the delights of this homely vegetable. There, I was introduced to a form of sauteed spinach that definitely caught my fancy. And this is how they do it: Wash a large bunch of spinach and remove tough stems. Put in spinner to dry. Heat 4 or 5 tablespoons of olive oil in a heavy bottomed sauce pan at moderate heat. Add finely minced garlic. As it turns golden, put in the spinach leaves and turn, coating the leaves with oil. Salt and pepper. Lowering the heat a bit, take a heavy wooden spoon and as the spinach wilts use the spoon in a downward motion breaking up the fibers. Continue doing this until the fibers are broken down but don't go so far as to make a puree. Take off heat and stir in a thick yogurt. Correct seasoning. This is best served at room temperature. Afiyet olsun as they say in Turkey; or, in other words, bon appetit.