Berkshire Author Kevin West's New Book Digs Into Vegetable Variety

berkshire-author-kevin-wests-new-book-digs-into-the-flavor-and-story-of-vegetable-veriety

berkshire-author-kevin-wests-new-book-digs-into-the-flavor-and-story-of-vegetable-veriety

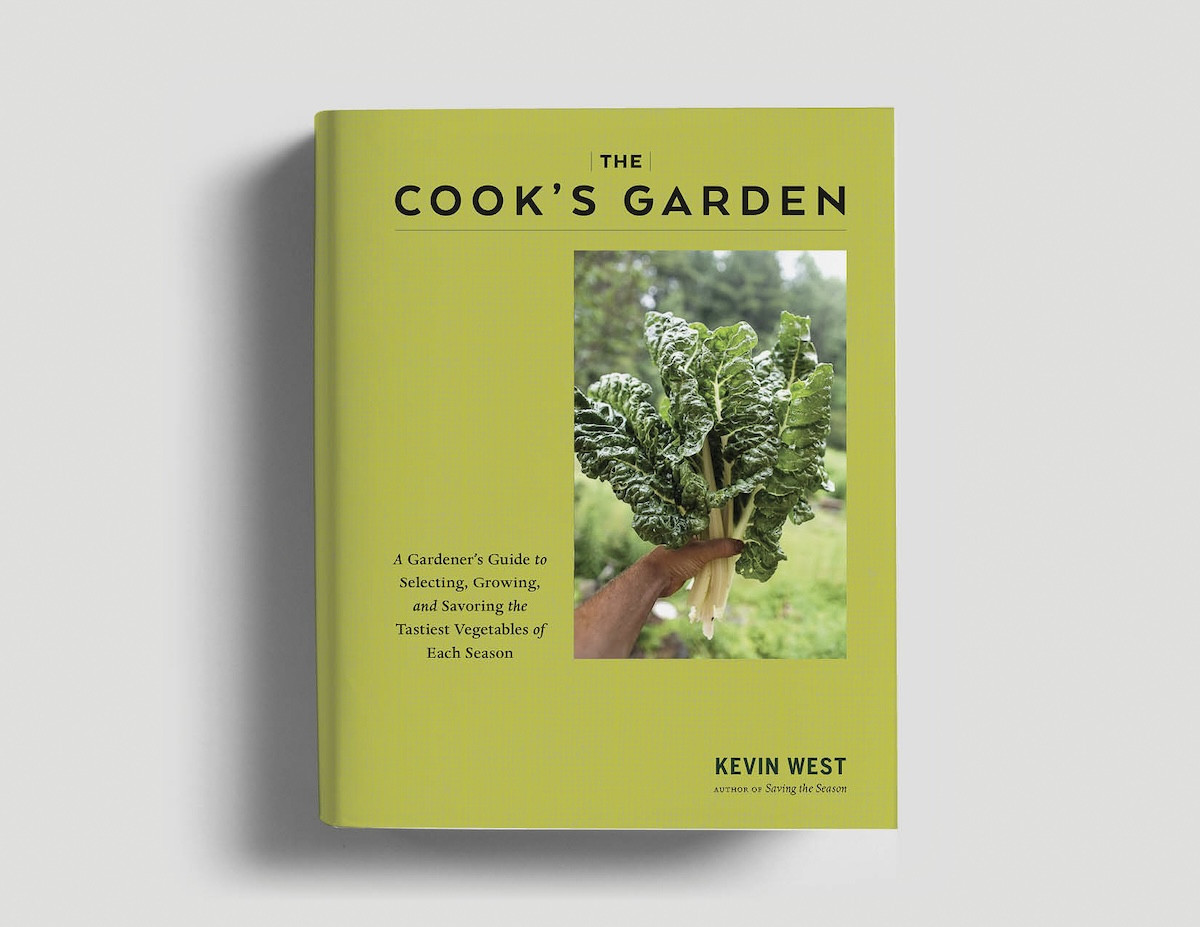

From East Tennessee farm fields to his sprawling garden in Berkshire County, Kevin West has chronicled the personalities and culinary purposes of his favorite vegetable varietals in his new book The Cook’s Garden: A Gardener’s Guide to Selecting, Growing, and Savoring the Tastiest Vegetables of Each Season.

It’s the first August day to feel like fall. It’s 58 degrees, and pouring rain waters the moat of foliage around West’s paint-stripped 1750 Colonial in the southern Berkshires. He throws open the side door. Lacking steps at the moment, the entrance appears to be floating a couple feet off the ground. He offers me a hand up through a gauntlet of bowing hydrangeas into the parlor.

Photo courtesy of Kevin West.

You say tomato, West says Brandywine, or Green Zebra, or Cherokee Purple. If it’s a cherry tomato: Sungold. Canning tomato? Try Amish Paste. His love of agricultural specificity fueled his 496-page gardener’s handbook and dirt-to-dinner table cookbook The Cook’s Garden, published August 26. I met West as a journalist, but I’ve come to know him as a certified Master Food Preserver, tree warden, and American Chestnut steward, and as a gardener and a cook. I also think of him as a sort of vegetable anthropologist. If Onion were a nation-state—in the geographic region of Allium, bordering Shallot, and Garlic—he’d peel back its layers, exploring cities, villages, and households, interrogating each variety’s own history, flavor, texture, and nature, informing its role in a meal.

As avid a gardener as West is, he doesn’t keep a garden here at home. Not long after he moved here in 2016, his neighbors Del and Christine Martin welcomed him to assist in, and gradually usurp, theirs. Now it's a sprawling plot, with a 60-by-78 foot deer fence, an elaborate irrigation system, and an abundance of herbs, radishes, salad greens, zucchini, tomatoes, collards, and more.

That’s where West first really delved into his fascination with the nuances of variety: “Everyone knows there are only two things that money can't buy, and that's true love and homegrown tomatoes,” he says from a chair near the fireplace in his sitting room, a frosted goblet of ale in hand, a plaster bust of Abraham Lincoln peering over his shoulder from atop the overflowing bookshelf behind him. West says he has no interest in “plastic-looking tomatoes,” anymore. “Now you get like these beautifully lumpy, and ruffled, and multicolored tomatoes.” He likewise appreciates how farmers’ market quality has drastically improved for different varieties of beans, and of peppers. He says shoppers and chefs are embracing how, “each has its own personality, and its own role in the kitchen.”

Photo courtesy of Kevin West.

The growing season here is short and cold compared to West’s hometown in East Tennessee. West’s grandparents were farmers in Blount County, their barn in view of the Great Smoky Mountains. His parents and neighbors all grew what they ate, living the locavore life before there was a portmanteau for it. He had the chance early on to develop an appreciation for the different flavors, uses, and personalities of different varieties.

By the time he was a teenager, he was dog-earing pages in cookbooks Julia Child would have had in her library, The Wonderful Food of Provence among them. He left Tennessee for college in California, and he left school for a gap year that turned into two, which he spent working under a revered fishmonger at Berkeley’s Monterey Fish Market and hanging around Alice Waters’s Chez Panisse, the cradle of the American farm-to-table food movement.

The people he met in the Bay Area transformed the way he thought about food. “I learned enough to realize that I loved food, I was very interested in the culture of the table—but I didn’t want to be a chef,” he says.

Photo by Alexandra Marvar.

Instead, he wrote, on staff at W magazine, in New York, Paris, Los Angeles… and, in 2013, while indulging in the bounty of California’s farmers’ markets, he found ways to overcome the heartache of his favorite fresh fruits and vegetables falling so quickly out of season: canning, pickling, and preserving. What started as a hobby spiraled into an obsession, and he put together his first cookbook, Saving the Season: A Cook’s Guide to Home Canning, Pickling, and Preserving.

In 2016, he made his way to his new home outside Great Barrington. He found the 1750 Colonial—with its original hardwood floors and its centuries-old iron fireplace pot cranes—and started, slowly but surely, fixing things up. Down the road at the Martins’, he dug into gardening with the same rigor he’d brought to preserving, in pursuit of flavor.

“That’s what led me to explore growing not just this bean, but also that bean. Not just a wax bean, but also a broad leaf bean,” he says. “I noticed, slowly at first, that different varieties have very different flavors, and qualities, and characteristics.”

Each of these different varieties, he adds, gives gardeners a chance to respond “to an opportunity, or a question, or a challenge.How do we make a tomato smaller? How do we make a potato bigger? How do we make cucumbers last longer on the vine? Every variety is someone's creative response to a question. I just became really interested in the creativity that's inherent in all of that.”

Photo courtesy of Kevin West.

This curiosity pays off in The Cook’s Garden. The cover is the chartreuse hue of a Romanesco broccoli tip and features a striking portrait of chard. Inside, West takes his appreciation for specific flavors to the extreme, examining vegetables beyond their family names—“as a collection of individuals,” each with its own origin story, cultural and political significance, culinary purpose, and flavor profile.

With the same affection Pablo Neruda once lavished upon the onion (“heavenly globe, platinum goblet, / unmoving dance / of the snowy anemone”), West writes about the distinct varieties of onions, beans, peas, greens, squash, root vegetables, cucumbers he loves best, laying praise evenly across all categories of produce.

Part one of The Cook’s Garden is devoted to gardening basics—soil, compost, harvest guidance, including inspiration and blueprints for the new gardener, and reassurance for the discouraged one. Part two,Vegetable Knowledge, examines what varieties are best for which purposes, and how to prepare, store, and cook them. And of course, there are recipes. Some are delightfully ambitious. Some, as the headnotes acknowledge, are hardly a recipe at all: More a simple piece of advice about, say, the single secret ingredient to pour over your baked winter squash, and a wink. (Spoiler alert: It’s heavy cream.)

“Gardeners are more familiar with the idea of varietal character, and I really want to bring that into the kitchen, to help cooks also appreciate the potential of varietal character,” he says, “even with things as simple as the kitchen staples like potatoes or garlic.”

On my way out the door, West presses two magic wands of garlic into my hand—Spanish Rojo and Uzbek—with serving instructions and a suggestion that I taste them side by side.

On the whole, West’s new tome might be as useful to the person cultivating a Brooklyn apartment’s window box as to the team tending a Michelin-starred chef’s potager. For this whole spectrum of readers, it’s a generous conveyance of wisdom. At the Berkshire Botanical Gardens on Saturday afternoon September 6, West will share some of that in person, in a class on growing a garden and cooking from it. At Hancock Shaker Village on September 13, he’ll impart lessons from the book and then see them come to life as Kevin Kelly, the chef behind After Hours GB, serves a Cook’s Garden-inspired farm-to-table dinner.