In organizing Call Me Melville, a summer-long festival celebrating Herman Melville and the work he’s best known for, Moby-Dick, Megan Whilden has discovered that “a novel about obsession breeds obsession.” For example, there’s the Brooklyn-based band Call Me Ishmael, which has composed 135 songs about Moby-Dick, one for each chapter of the book. There’s collector Bill Pettit of Albany, New York, who has accumulated more than 200 copies of Moby-Dick. And there’s the artist Matt Kish, who made 552 drawings inspired by the novel—one for each page of his Signet Classics paperback edition. (Kish’s book, Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page, was published by Tin House Books last year.) All three will be featured at the festival, which Whilden has launched in her role as Director of Cultural Development for the City of Pittsfield.

“There’s a lot of people coming out of the woodwork with these fantastic ideas,” says Betsy Sherman, director of the Berkshire County Historical Society, which is based at Arrowhead, the 1783 farmhouse on Holmes Road in Pittsfield where Melville and his family lived from 1850 to 1863. “They’ve taken [Melville and Moby-Dick] to heart and found their own inspirations.” Call Me Melville is the fifth in a series of Pittsfield-based festivals inspired by classic books, including Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods in 2008; Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird in 2009; Tim O’Brien’s The Things We Carried in 2010; and Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451 last year. “We have a history of engaging people through books, but using a wide variety of art forms to do so,” including music, dance, theater, film, and visual art, says Whilden.

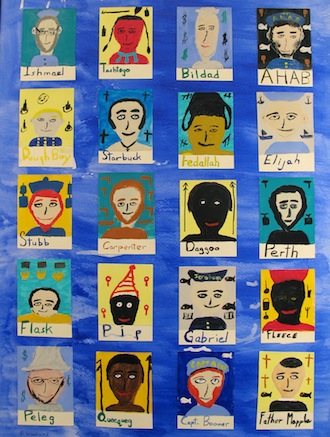

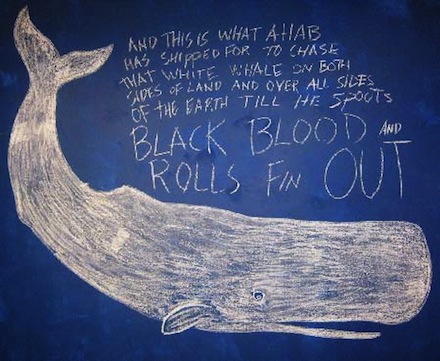

Subtitled “The Power of Genius: Landscape and Inspiration,” the festival encompasses an impressive and delightful array of Melville-related activities and art. They include (to name just a few) a burlesque dance performance inspired by the great white whale; a Polynesian-style luau reflecting Melville’s travels and writings in the Marquesas Islands; and a life-size hay sculpture of Moby’s tail, by Plainfield artist Michael Melle, to be displayed on the grounds of Arrowhead. The visual arts component stretches from Pittfield's Ferrin Gallery, where Paul Graubard's folk art paintings (like Moby Dick, left) are on display, to Time &Space Limited in Hudson, where co-founder Linda Mussman's installation, M... M... M... ...Oil, inspired by Moby-Dick explores the obsession with oil, past and present. (Below, left, is a selection from her show). Also on the schedule: a one-man theatrical production of Moby-Dick by the Gare St. Lazare Players of Ireland; staged readings and original theater works; shows of scrimshaw and photography; and other events, ranging from the expected to the downright quirky.

The centerpiece of the festival is a communitywide online reading of Moby-Dick, created in partnership with PowerMobyDick.com. The book’s 135 chapters will be posted one by one each day, beginning on Memorial Day weekend. (An audio version will also be available.) Readers can comment on the annotated chapters via Facebook, Twitter, and the Berkshire Eagle’s website. While appealing to younger tech-savvy readers, this approach also offers a convenient alternative to traditional face-to-face discussion groups, which Whilden says had the lowest attendance of all the events during past book-focused festivals. “From high school kids to Melville experts, we can all hold hands and read it together, and people can participate from next door or from around the world,” she says. This year’s choice doesn’t celebrate any particular Melville-related anniversary, but it does catch a wave of renewed interest in the author. Nathaniel Philbrick’s book Why Read Moby-Dick?, published earlier this year by Viking, brought the classic into the spotlight again. Bartleby the Scrivener, the title character of Melville’s 1853 short story—a clerk who passively resists the orders of his Wall Street employer—has become an unofficial mascot for the Occupy Wall Street movement. The festival aims not only to “bring Moby-Dick alive for a new generation of readers,” says Whilden, but also to conjure up the author “outside the dusty old historic box”—as a flesh-and-blood citizen of Pittsfield who did research in the local library, visited with the Shakers at Hancock, and hiked the land with his friend and neighbor Nathaniel Hawthorne, finding inspiration in town and country. The stern and craggy visage of Captain Ahab was evidently inspired by Melville’s sighting of a tree struck by lightning in the middle of downtown Pittsfield, and he named his farmstead after the arrowheads he found in the nearby fields.

Though Melville spent only 13 years in Pittsfield, “this is the place where his story gained prominence,” says Sherman. “This was where he was most productive in terms of writing—even though Moby-Dick was a failure.” Yes, you read that right. Moby-Dick sold so poorly that, when the New York City warehouse where the books were stored burned to the ground, the publishing company refused to reprint it. It wasn’t until Melville scholars, notably Raymond Weaver, brought Melville’s Billy Budd—published in 1924, 33 years after Melville’s death—to the public’s attention that Moby-Dick was resurrected, along with interest in the place where he had written the manuscript.

From the window of his second-floor library at Arrowhead, Melville could look directly out on Mount Greylock, its mottled hillside rising up into the sky—not unlike a giant whale breaching. In Moby-Dick , he compared the great white whale to “a snow hill in the air,” Sherman says. “I have a sort of sea-feeling here in the country, now that the ground is all covered with snow,” Melville wrote in December 1850. “I look out of my window in the morning when I rise as I would out of a port-hole of a ship in the Atlantic.” “Melville wrote the most famous seafaring novel in a landlocked city in the Berkshires,” says Whilden. “He saw the whale right here.” —Tresca Weinstein