Cloud Warriors: Veteran Journalist Thomas Weber Uncovers How We Control the Weather

Weber will discuss his new book at the Roeliff Jansen Community Library in Hillsdale October 8.

Weber will discuss his new book at the Roeliff Jansen Community Library in Hillsdale October 8.

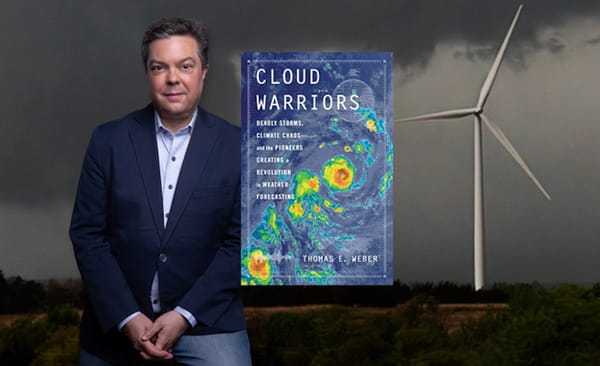

Thomas Weber and his new book, Cloud Warriors.

When Thomas Weber wakes up at his weekend home in Austerlitz, one of the first things he does is check his Tempest weather station. Perched unobtrusively on the property, the small set of equipment feeds a stream of hyperlocal readings to his phone: wind, rain, temperature, humidity, lightning alerts, and more. For Weber, a former Wall Street Journal columnist and Time magazine editor, these numbers aren’t just curiosities. They are the self-actualization of a quiet, community-driven forecasting revolution.

His new book, Cloud Warriors: Deadly Storms, Climate Chaos—and the Pioneers Creating a Revolution in Weather Forecasting, makes the case that while humanity cannot control the weather, we already exert tremendous influence over its impact. And with extreme events mounting, like catastrophic hurricanes, sudden floods, record heat, the stakes have never been clearer. On October 8, Weber will bring this story to the Roeliff Jansen Community Library in Hillsdale for a free author talk.

A typical National Weather Service forcaster's workstation. Photo by Thomas Weber.

Weber’s journalistic path began in small-town Massachusetts. Fresh out of college, he filed stories for a daily so modest in circulation that, he recalls, “it was smaller than my college paper.” But those early years taught him something enduring. “You really felt connected to the readers and the community. I’d cover a school board meeting, the story would be in the paper, and the next day someone would stop me on the street to ask about it.”

After his stint at the Wall Street Journal, Weber worked as a technology reporter during the heady days of the dot-com boom, covering the internet’s rapid expansion. “I remember using the word blog in the paper for the first time,” he recalls. His fascination was always at the intersection of science, technology, and society.

Inspiration for his new book came out of the blue one morning while asking Alexa about the day’s weather and getting no response because a storm had knocked out the internet connection. “It’s information I depend on every day,” Weber says. “It’s information we all look at every single day. And I thought, for a science and tech guy, I really don’t understand that much about where this information comes from,” he says.

Storm-chasers at the National Severe Storms Laboratory ready heir equiptment. Photo by Thomas Weber.

One of the book’s central insights is that weather forecasting is not just about the accuracy of models, but about how people use—or fail to use—them.

In Norman, Oklahoma, Weber visited the National Severe Storms Laboratory. There, among the physicists and meteorologists, he met a tornado researcher whose focus was not the storm itself but the people in its path. “Her work and her team were centered around the thought that the tornado warning system was pretty good, but people were injured or died anyway,” Weber recounts. “So what happened there? Focusing on what people are doing in response to an alert was really a shift in approach. People think of forecasting as satellites and radar, but one of the most important things we may be able to do going forward is look at the people who use the forecasts and make sure they can understand them and put them to work.”

This realization reframed his thinking. “We do have agency in how we respond to the weather. We don’t have complete agency, of course. But we have agency to monitor forecasts, take steps to protect ourselves, and make smarter decisions. I hope everybody who reads the book comes away feeling a little more empowered to look at the forecast and then think about how they can put that into action.”

That empowerment, however, depends on strong public weather research institutions, and Weber worries those are being undermined. “We’re really on the verge of a new age of accuracy,” he says. “The last giant leap came all the way back in the ’60s, when we had the advent of satellites and radar and digital computers. Now we’re on the verge of tools like AI and new types of satellites. But I think it was just this week that it looks like they’re cutting funding to one of the big AI weather research centers at the University of Oklahoma.”

He is blunt about the consequences: “People always talk about, oh, don’t eat your seed corn. But this is like we’re taking our seed corn and putting it in a pile and setting it on fire. We’re squandering our future progress.”

Weber notes that earlier in the year the National Weather Service eliminated hundreds of jobs, mostly indiscriminately, before scrambling to hire back new staff in the wake of disasters like the recent Texas floods. Operational forecasters, the people who staff local offices around the clock to issue advisories and warnings, are stretched thin. “The consequences may not really make themselves clear for years to come, where we’re pulling back from the work that would improve our forecast,” Weber warns.

If institutional support is faltering, individuals can still take part in building resilience. For Weber, that means running his own weather station. His devices, which collectively only cost a few hundred dollars, share data with networks that improve larger models. “It’s partly a fun hobby, but partly a way to get a more accurate and helpful forecast,” he explains. “In our world of data, the more people who install their own sensors, the more different types of data we start feeding into forecast models, the better our forecasts will get.”

Asked what worries him most in this region, Weber doesn’t hesitate. “Flooding is probably the biggest weather threat for people here to worry about, and that’s partly because it’s generally the most unappreciated threat,” he says. Unlike tornadoes, which inspire immediate alarm, floods are often underestimated, until it’s too late. “One of the biggest changes in my own life after spending the last several years researching all of this is I am personally much more scared of flooding, and much more aware when the forecast calls for it.”

Wind, falling trees, and flash floods from severe thunderstorms loom large. Longer term, he points to heat waves and poor air quality from wildfires as increasingly pressing hazards. Each example reinforces his central message: Preparedness is possible, but only if people pay attention to the forecast and act on it.

Despite such sobering realities, Weber remains optimistic—and hopes to pass that optimism on. “The cliche is that the weatherman is always wrong,” he says. “But a five-day forecast now is as accurate as a one-day forecast from 20 years ago. Hurricane track forecasts in the last 20 years have become amazingly more accurate,” he says. “Almost any category you can look at, forecasts keep getting better. That’s powerful information if we can put it to work.”

On October 8, he’ll share that conviction at the Roeliff Jansen Community Library in Hillsdale. The event, free and open to the public, runs from 6 to 7pm and will feature a discussion of Cloud Warriors along with practical advice for individuals navigating hazardous weather. Attendees can expect to learn which information sources Weber trusts, how he interprets watches and warnings, and why he believes everyone can become a savvier consumer of forecasts.

“I hope people come away both appreciating how good forecasting is getting, and why we should support it instead of cutting the money that funds it,” Weber says. “But finally, I hope they leave knowing how to be savvier consumers of weather information themselves.”