When Ellie O’Heaney was in fifth grade, she didn’t picture college in her future. Diagnosed with dyslexia years before, she’d grown accustomed to feeling frustrated and adrift in the classroom. “She’d say, ‘Why would I willingly go on to more school?’" her mother Elizabeth O’Heaney recalls. “‘I’m only doing it now because I have to.’" These days, Ellie is singing a different tune. An eighth-grader at the Kildonan School in Amenia, New York, she’s learned to appreciate the talents she has because of--not despite--dyslexia. “She’s completely empowered," her mother says. “She thinks her brain is superior to mine. And I agree with her!" Ellie’s transformation was made possible by Kildonan, which helps students with dyslexia identify their strengths and use them to meet linguistic challenges. O’Heaney, a special education teacher, believes her daughter’s experience should be the rule, not the exception. To that end, she’s teamed up with Kildonan headmaster Kevin Pendergast and national mentoring organization Eye to Eye to sponsor Discussions on Dyslexia on Sunday, April 21.

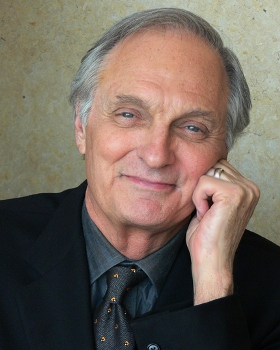

Four leading experts on dyslexia will form a panel to discuss the neuroscience behind a diagnosis that’s often misunderstood. A cash bar, dessert reception, and raffle with prizes like a week-long stay at a Vermont farm round out the event. And lending the event star power is moderator Alan Alda, an actor and science enthusiast who also happens to be Ellie’s grandfather. O’Heaney and Pendergast (pictured below with Ellie) say their goal is to help parents, educators, administrators, and the public better understand dyslexia as an alternative way of processing information. One important thing to know, Pendergast says, is that although dyslexia is often portrayed as a problem, it actually comes with many benefits and unique talents. For one thing, most dyslexics see images in three dimensions. Pendergast says this makes processing written language more difficult. “Non-dyslexics must have invented written language and given it two-dimensional symbols," Pendergast says. That’s why a person with dyslexia might look at a lowercase b and see a p or q. But while three-dimensional visualization can make linguistic learning more challenging, it also makes dyslexics exceptionally gifted in fields from art and architecture to engineering. O’Heaney says she’s amazed by her daughter’s problem-solving skills, which allow her to do things like mentally rearrange spaces for maximum efficiency.

Take their family’s recent trip to check out a farm for sale. O’Heaney told Ellie that while the house seemed just right for their needs, the barn looked too small. “She was like, ‘Give me a minute,’“ O’Heaney says. “And she redesigned the entire barn in her head, saying what about this: We build out from this side, put a couple more stalls over there, add a washroom over on this side. She thought of where the stall doors would go, where the water’s going to come from, where we’d wash horses, where we’d throw hay out of stalls. She thought of everything." The more people understand the wide range of strengths that people with dyslexia possess, O’Heaney says, the more educators can use that knowledge to inform instruction for dyslexic students. “It doesn’t take a lot to include dyslexic kids in mainstream classes," she says. “But they get excluded because they have fallen so far behind that they can’t be remediated in the classroom. We want educators and administrators to start having conversations about how to catch it earlier, so that dyslexic kids can be included in regular education." To help reach that goal, Discussions on Dyslexia is inviting donors to sponsor tickets for teachers from area schools who couldn’t otherwise afford to attend. And proceeds from the event benefit two organizations committed to helping dyslexic students: Kildonan and Eye to Eye, a national mentoring program that pairs children with language learning disabilities with adults with similar labels. Pendergast says that meeting successful adults with dyslexia inspires students to imagine exciting, fulfilling future careers for themselves. In fact, he says, dyslexics tend to be some of the most innovative thinkers around. “Go into any office building," Pendergast says, “and ask who are your best problem-solvers, who are the most creative—there’ll be people with dyslexia all over that list." --Sarah ToddAlan Alda Talks With the Experts: Discussions on DylsexiaSunday, April 21, 2013 Cash bar open from 6:00 pm to 6:50 pm; Program begins promptly at 7:00 pm Chelsea Morrison Theater, The Millbrook School 131 Millbrook Road Millbrook, NY 12545 (978) 886-3600 To purchase tickets, click here.