Edna St. Vincent Millay and Steepletop: 100 Years Later

The Millay Society plans a centennial slate of events to honor the poet and her home here.

The Millay Society plans a centennial slate of events to honor the poet and her home here.

Along the eastern border of New York, bordering Berkshire County, sits Steepletop, a handsome 200-acre farm in Austerlitz. The property has been filled with history, mystery, and literary legends ever since becoming the home of poet Edna St. Vincent Millay 100 years ago.

Steepletop’s stewards, The Millay Society, kick off a centennial celebration on April 26 with an event at the Spencertown Academy Arts Center where author Krystyna Poray Goddu will present a look at the life and work of the legendary poet, and how Steepletop has changed over the years.

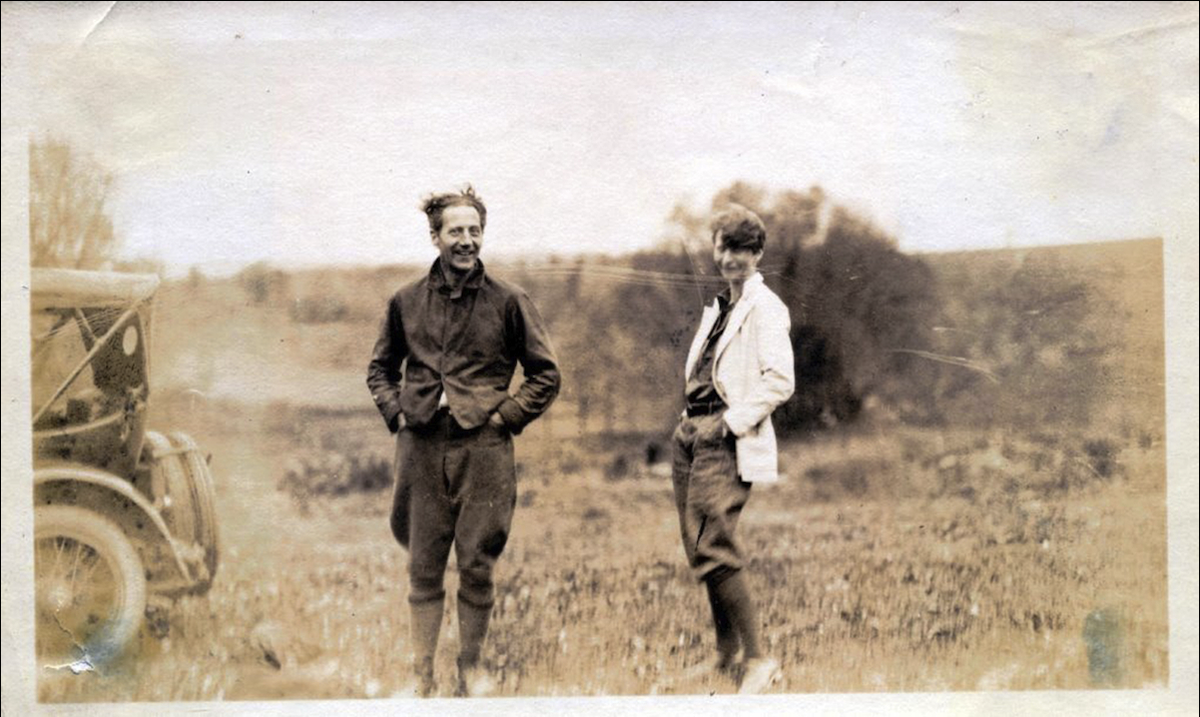

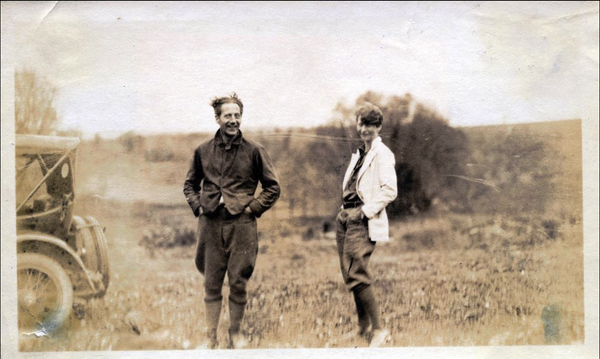

On May 21, 1925, Millay and her husband, Dutch businessman Eugen Boissevain, bought a run-down 435-acre dairy farm with abundant blueberry bushes for a mere $ 9,000, only two years after Millay won the Pulitzer Prize. They named it Steepletop, for the abundant steeplebush (Spirea tomentosa) that flourishes here. In a letter to her mother, Millay writes that the property was “one of the loveliest places in the world.”

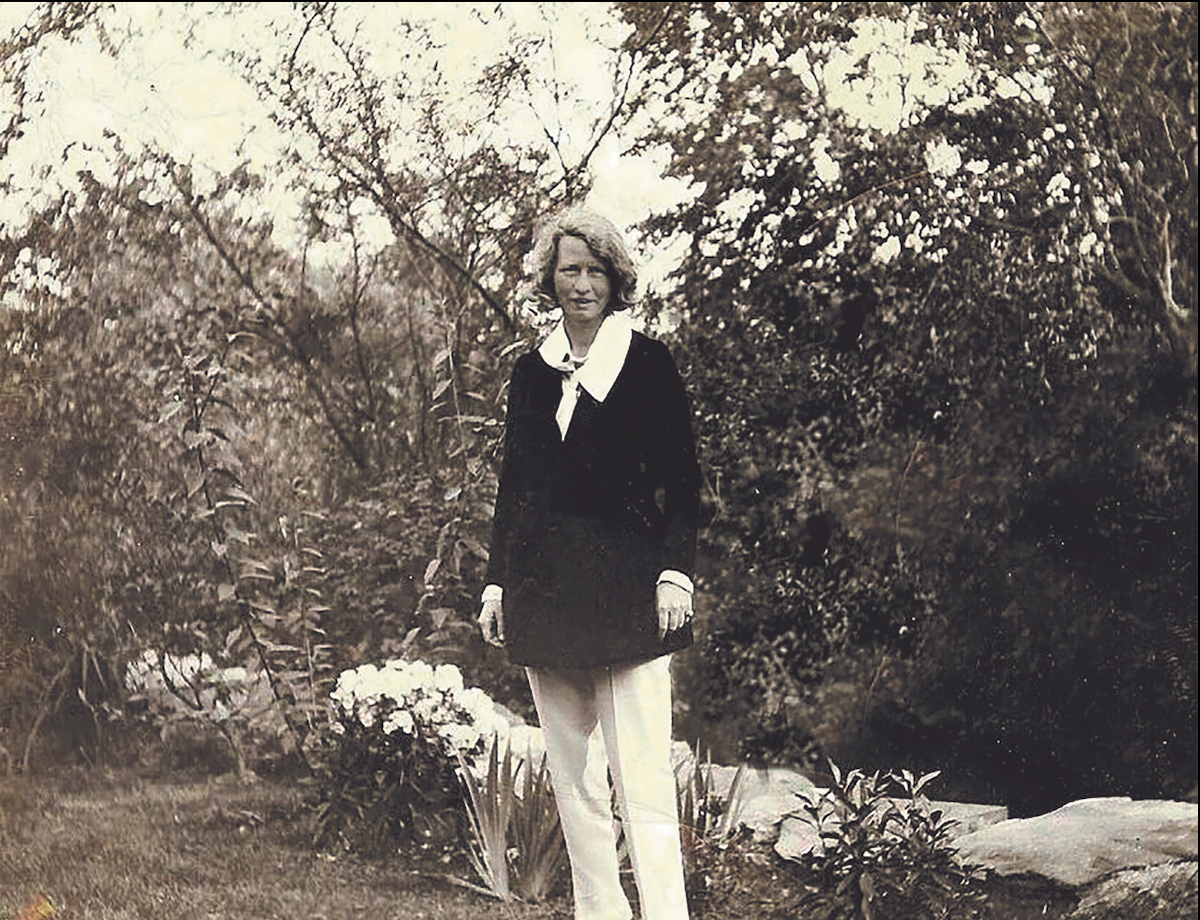

Millay was at the height of her fame then, a fame so blistering that today it would rival that of Taylor Swift. Steepletop was Millay’s refuge from the chaos of that public life. To be sure,Millay was the “It” girl of Greenwich Village, a genuine Jazz-Age icon. Audiences were compelled by her many contradictions: at once touted by the media as “a fragile child,” for her seeming frailty and small stature, but strong enough to attract, engage, and entertain enormous audiences as she recited her poetry at events all across the United States, surprising one and all with her command of language and her bright-red hair.

According to Nancy Milford’s biography Savage Beauty, Millay became the herald of theNew Woman. “She smoked in public when it was against the law for women to do so, she lived in Greenwich Village during the halcyon days of that starry bohemia, she slept with men and with women and wrote about it in lyrics and sonnets that blazed with wit and a sexual daring that captivated the nation.”

During Millay’s heyday in the 1920s and `30s, her poetry was widely read and deeply admired by both the public and critics, here in the US and in Europe. Adding to her fame were her electrifying performances, often given before packed audiences. On a visit to Los Angeles, she sold out the Hollywood Bowl three nights in a row. (The Taylor Swift comparison isn’t hyperbole after all.) By the mid-1930s, Millay was the most famous woman in America.

The nonprofit Millay Society maintains Steepletop, including Millay’s gravesite and an interpreted poetry trail. The group will launch a year-long celebration with Goddu’s talk in Spencertown. Goddu serves as the literary officer and secretary of the Millay Society Board. Goddu is the author of the 2016 book for readers ages 10 and up, A Girl Called Vincent: The Life of Poet Edna St.Vincent Millay.

She’ll discuss Millay’s childhood in Maine, her years at Vassar College and in Greenwich Village, and her groundbreaking poetry. “I’ll show photos of Steepletop and how Millay and her husband changed it, and what the Society has done to keep Millay’s legacy alive,” Goddu says. “Because of my book, I’ve done lots of school programs. My talk on Saturday will expand on those programs and include the adult details I usually have to leave out!”

While Steepletop usually opens to the public only a few times a season, the Society's board intends to change that in the centennial year. “The whole point is to introduce Steepletop to people who have never been,” Goddu says. Among the new faces Goddu hopes to attract include volunteers to populate upcoming spring clean-up days, which are scheduled for Sunday, April 27, May 18, June 1, and June 8, all from 9:30am to 12:30pm.

Visitors will be invited to explore Steepletop’s gardens, pool, poetry trail, writer’s cabin, and the rest of the acreage on self-guided tours one weekend (both Saturday and Sunday) every month from June through October. They are June 14-15, July 12-13, August 9-10, September 13-14, and October 11-12. “We will have musical performances on four of the five weekends,” Goddu says, “and a plein-air painter for the other.” Tickets are $10 per person. Docent-led tours of the Millay house are also available, but must be reserved in advance.

A tour of Steepletop.

“I discovered Millay when I was 12 years old,” Goddu says. “And I count myself as one of those inspired by her poetry. Her sonnets are ground-breaking because she used this classical form to express very modern feminist sentiments. At the time Millay wrote them, they were shocking.” Goddu’s favorites are the love sonnets. “There was always a Millay sonnet to accompany my every life experience.”

Tim Hawley, a Millay scholar and former docent at Steepletop, echoes Goddu, and says Millay’s mark on the public has been profound and long-lasting, indeed. “As part of my tour I’d read a Millay poem and often look up to see tears streaming down the face of a visitor or two.”

Immediately after purchasing the farm, Millay and Eugen removed the Victorian-era adornments from the farmhouse and began making essential upgrades and improvements. In a letter to her mother, Millay said she was as likely “to pick up a screwdriver as a pen,” as her work on the house was so encompassing. The couple also farmed the land and ran a dairy, employing numerous local workers during the Depression.

They loved to entertain, too, and they held many parties at Steepletop over the years. Millay and Eugen even designed a dedicated outdoor area for entertaining that includes themed gardens, a clay tennis court, a spring-fed swimming pool, pergola, and cocktail bar. “They had infamous parties, some that were clothing optional,” says Goddu. “Millay famously said, ‘The flowers were watered with gin.’” That’s not hyperbole, either—according to one former docent, piles and piles of empty Dixie Belle Gin bottles have been found on the farm.

For the next 25 years, Millay continued her literary career at Steepletop, writing a number of her best-known and much-loved poems in the humble cabin a stone’s throw from the farmhouse. Millay died at Steepletop in 1950 at the age of 58, and is buried on the property.

Its beauty and literary legacy aside, The Millay society is also a protector of Steepletop’s ecology. Its mix of farm fields, northern hardwood forest, and wetlands is the largest private property surrounded by the Harvey Mountain State Forest and part of a contiguous 4,000-plus acre block of state land where important native species thrive, including rare butterflies, multiple bird species, transient moose, bobcats, and fishers. Millay was an accomplished amateur naturalist and could identify all the birds, wildflowers, mushrooms, and other growing things at Steepletop,” Hawley says. “She was particularly knowledgeable about medicinal plants, thanks to her mother’s instruction.”

A study by Hawthorn Valley’s Farmscape Ecology Program reported in 2020 on the biological inventories it had conducted over the prior decade. The report revealed 268 plant species found at Steepletop, of which 192 were native. They also inventoried an ancient forest here (defined as a forest that has never been clear-cut), primarily of oak and maple.

In January 2025, a conservation easement many years in the making was finalized to permanently protect Steepletop. “This is an important milestone for The Millay Society,” says Vincent Barnett, its current president. Partner organizations, including Scenic Hudson, the NYS Department of Conservation, the Land Trust Alliance, and the new Forest Conservation Easements for Land Trusts, ensure that Steepletop became a part of an important belt of forests and farmland in Columbia County that supports wildlife habitat, species diversity and strengthens the ecology overall, according to Seth McKee, Executive Director of the Scenic Hudson Land Trust. “The protection of Steepletop means future generations may now experience the same beautiful unfragmented, forested and agricultural landscape that inspired Millay,” he says.

The Austerlitz Historical Society (AHS) has a living-history project about Millay in the works, set to open in the fall. Austerlitz resident and AHS Board Member Tim Hawley seeks to contact any resident of the area who has a first- or second-hand anecdote about Millay’s life in Austerlitz.

Nancy Kern, for example, remembers being a student at the one-room school in the hamlet of Austerlitz when her teacher called the class to the window one winter’s day as Millay went cruising by in a horse-drawn sleigh.

For the full slate of events and information on how to take part visit the Millay Society’s website.