Forge Project: A Native-Led Initiative On The Homelands Of The Muh-he-con-ne-ok

Based in Taghkanik, the organization supports Indigenous leaders in Native culture and activism.

Based in Taghkanik, the organization supports Indigenous leaders in Native culture and activism.

The buildings housing Forge Project in the Columbia County town of Taghkanic were designed by artist/ activist Ai Weiwei.

- Alon KoppelAfter earning a master’s degree in US history, Heather Bruegl, a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and a descendant of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, was unsure of what career path she wanted to take. On a visit to South Dakota with her husband, the pair stopped on the plains of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The reservation is the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre, where US Army soldiers killed nearly 300 Lakota people following a failed attempt to destroy the Lakota camp after years of land seizure and conflict.

Sitting there, Bruegl found her calling. “The breeze was blowing. I kind of felt like the ancestors were calling and telling me, ‘What you’re going to do is talk about us. You’re going to talk about our history, and the importance of Indigenous histories and being an Indigenous woman,’” she says. “From that moment on, I didn’t look back.” Bruegl has traveled as a lecturer and worked as the director of cultural affairs for the Stockbridge-Munsee band of Mohican Indians in Wisconsin.

Today, the Stockbridge-Munsee people no longer have land in the Northeast. They descended from the Mohicans, known ancestrally as the Muh-no-con-ne-ok peoples, and the Munsee peoples. The tribes lived in the Hudson Valley and the surrounding region, but were forced west by European settlers. They relocated to Wisconsin in the early 1800s and have a reservation in Shawano County.

Bruegl’s mother grew up on the Stockbridge-Munsee reservation, which the family visited throughout Bruegl’s childhood. They stayed at her uncle’s cabin on the banks of the Red River, which runs through the territory, and watched Indigenous ceremonies. “When I’m approaching the pow wow grounds and I hear the drums — that music, the drums, the dancing is medicine, it’s healing,” says Bruegl.

Last summer, Bruegl moved to the Columbia County town of Taghkanic and started working at the Forge Project as its director of education. Living on her ancestors’ homeland is fulfilling. “ “Knowing that my ancestors walked on this land here, and had homes and communities was really cool,” she says.

An Evolving Organization

In early 2021, philanthropist Becky Gochman bought the Tsai residence in Taghkanic. The two structures are the only ones in the US designed by the Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei. They were commissioned by Christopher Tsai, a collector of Weiwei’s work, and built in 2006.

The larger building, outfitted with a gray exterior, is the main residence. It resembles a two-story house with an open-concept floor plan. The second structure, a red Y-shaped building, functions as a guest house, housing a gallery and studio apartment. They overlook expansive fields surrounded by forests.

According to cofounder Zach Feuer, Gochman purchased the 38-acre property to house an initiative that would use art to positively impact the area. She asked Feuer, a local art curator, to help. After Feuer attended a talk that Bruegl gave on the Stockbridge-Munsee community’s Taghkanic origins, the pair chose to make Forge Project an initiative supporting Indigenous people, with Bruegl’s guidance.

Bruegl believes that a main focus for Forge should be to support underserved Indigenous leaders. “The idea of funneling resources toward those in Indian country and Indigenous artists who may need the extra lift obviously came to mind and was something that I thought could be very useful,” she says.

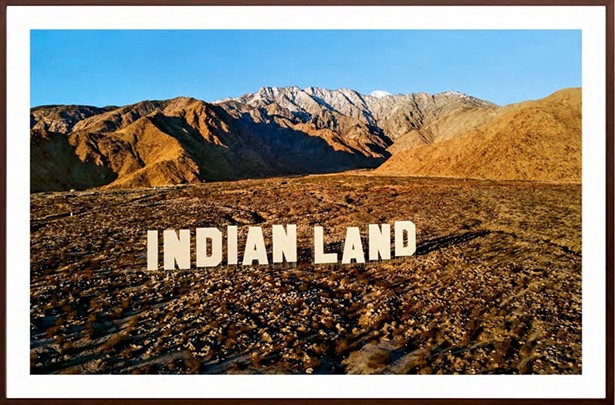

Nicholas Galanin's Never Forget is part of the Forge Project art collection.

As the three developed Forge, Candice Hopkins (Carcross/Tagish First Nation) joined as executive director. Hopkins wanted the initiative to expand public access and knowledge of Indigenous art, and to challenge longstanding systems of oppression. “I feel like the story of Native American art, in particular, has been left out of the development of American art,” says Hopkins. “What intrigued me about Forge was also its commitment to decolonial education. A lot of New York State is really the site of pretty massive displacement of Indigenous people, historically. So, what does it mean when folks start coming back?”

With Bruegl and Hopkins on board, Forge Project launched in August as a Native-led initiative supporting Indigenous leaders in several areas of culture and activism, including land justice, food sovereignty, and decolonial education. In addition to helping Native activists, they also educate the public on Indigenous life and history.

Working to Uplift and Educate

The initiative operates through four programs: a teaching farm created with Sky High Farm; educational programming; a lending art collection featuring Indigenous artists’ work; and a fellowship program benefitting Indigenous leaders from various disciplines.

Forge is developing the teaching farm with Sky High, an Ancramdale nonprofit that donates all of its food to food pantries, food banks, and other food access organizations around New York State. They will work with other organizations in Indigenous, Black, and migrant communities on addressing food security and supporting communities agriculturally.

Bruegl plans educational programs about Native American life. “A lot of the work that I do is rooted in historical context,” says Bruegl. Previous events include discussion of the epidemic of violence against Native American women, and how reports of it often don’t make headlines.

Forge’s lending art collection, made up of contemporary works by local and Native artists, also explores issues facing Indigenous people. Anyone interested in studying the artwork can borrow it. So far, Forge has loaned pieces to museums, galleries, and art organizations across the US, Canada, and Europe. Paintings, sculptures, and embroidered clothing items are installed throughout both buildings.

Much of the current work has activist themes. A print by Nicholas Galanin styles the phrase “Indian land” in the likeness of the Hollywood sign, reflecting themes of land justice. A drum with the words “land back,” painted by Corey Bulpitt, hangs in the residence’s entryway. “I always find that Native art has this lightness and humor and play, and that’s absolutely represented in the work at Forge,” Hopkins says.

The residency program financially supports Indigenous artists, educators, and leaders of other disciplines. “We have a lot of boots-on-the-ground Indigenous activists who are working really hard to bring awareness to issues in Indian country, but don’t always have the resources to do the work,” says Bruegl. Four fellows, each given a $25,000 stipend, stay at Forge and work on their practices. One of the fellows will always be from the Stockbridge-Munsee community to acknowledge the land that Forge rests on.

Creating a Different Kind of Future

Bruegl is planning lessons on decolonization in museums and other historical spaces, and children’s programming focused on Indigenous art. “I want people to be able to look at Forge and know that this is the place you can go to learn about really anything in Indian country,” she says.

The initiative supports activists’ voices in a time when Bruegl says they are demanding change. “The original inhabitants of this land are not going anywhere, and we’re not going to go quietly into that good night,” says Bruegl. “We’re here, we’re going to make a ruckus, we’re going to make you listen to us, and we’re honoring our ancestors and honoring ourselves.”

Upcoming Forge events

Sustainers of Culture and Life: Mohican Women’s Artistry and Food Cultivation in the Homelands

Wednesday, March 16, 2022, at 6 p.m. via Zoom

An Evening With the 2021 Forge Project Fellows

Friday, March 25, 2022, at 6 p.m. at Forge