AgriCulture bloggers Peter Davies and Mark Scherzer are the owners of Turkana Farms in Germantown, NY. This week Peter writes.

It is with a great sigh of relief that Mark and I find ourselves the day after Thanksgiving restoring order to the house and farm. The intensely deadline oriented nature of the holiday — meaning that everyone must have a fresh turkey on the same day — creates a lot of stress and a great burst of energy here at Turkana. Since April we have enjoyed seeing our Bourbon Reds, Narragansetts, Spanish Blacks, and Holland Whites pass through their various stages of growth and development; incessantly active and vivacious, gorgeous, despite their grotesque heads, entertaining us until the end with their colorful feather displays. It was hard to imagine as the time came to “send them to market” that they had arrived from the hatchery as day-old poults, all fitting into a single, small cardboard box. Their final day began at 5 a.m. on Monday, when Mark and I arose, hastily breakfasted, and trooped in the dark up to the barn to meet the truck/trailer we had hired for transporting the turkeys across the river to the slaughter house. Our farm helper, Eli, arrived as we were opening the doors to the turkey sleeping annex. As we had planned, our hundred or so birds were still sleeping, roosting in orderly rows on their perches. Taking them by surprise in the dark we have found is the least stressful (for them and us) way of moving them from their sleeping shed to the trailer. At first, the gathering was relatively easy — like picking oversized fruit — as we reached up grasped them by the legs and carried them upside down to the trailer. I was glad I could not really see them, nor they me, as after caring for them for five months, I always feel on this day that I have somehow betrayed them. Only the last twenty or so, coming to life as the day dawned, required a helter skelter, fluttering, madcap chase to entrap them.

Once they were loaded, and the trailer door slammed shut, I felt the usual sadness (“poor things” is the refrain that goes through my mind). And also I felt a kind of gratitude that I would not have to accompany them to the slaughter house. In the past, until a few years ago, I did accompany our turkeys on their final journey, and helped move them from the trailer to the killing floor, but never enjoyed being a witness. After their early departure on Monday, I did not see them until later that afternoon when they came back to the farm, gutted and dressed, neatly encased in plastic bags, packed tightly in large storage cases filled with ice. I could not help thinking of the storage cases as coffins and the garage, which we had set up for distribution, as the morgue. I did not rush in to examine them but could only half heartedly ask Mark, “Well, how do they look?” And with that question a subtle change had begun to take place in my reaction to them, a change that never ceases to amaze me. With that question they have somehow begun to become something else; a food commodity, not the lively sentient beings I had cared for. I had spent the afternoon preparing the tags identifying the customer to whom they now belonged, but now it was time to affix them to the individual turkeys. As [I accompanied Mark as] the turkeys were organized for the distribution I found myself examining the turkeys in what was becoming a purely objective way: I was pleased at the weights they had reached, how pure, and white their skin was, and at how neatly they had been plucked. It came to me that I was seeing them the way most purchasers first see their turkeys at the supermarket, as a food commodity completely divorced from its former existence. As our customers arrived at the farm to claim them, I found my feelings towards the turkeys changing once again: I could not help feeling a certain amount of pride that, once again, we had managed to produce such an excellent product, and felt full confidence that our customers would be more than pleased, that the turkey would be the high point of their holiday meal. . On Thanksgiving morning, it was time to turn to the turkey we had reserved for ourselves. I no longer felt any qualms as I lifted our beautiful bird from the refrigerator and began preparing it for the oven. Stripped of its feathers and no longer filled with life it seemed strangely anonymous. I reached into its vent and pulled out the giblets, liver, and neck and set them aside for gravy and stuffing making. As I slid my hand between the skin and flesh of the bird to smear the emulsion of butter, garlic powder, and herbs, my only concern was that in the process I did not tear the skin. In my mind the bird had now metamorphosed into the future centerpiece of our Thanksgiving feast. The final stage of metamorphosis took place once the bird was slid into the highly heated oven, and its ghostly white skin gradually turned a golden brown. The transformation was not just visual but olfactory as well, as delicious odors, a combination of roasting bird and herbs permeated the kitchen. The ghostly appearance and mild, dull odor of the bird as it rested in its ice filled coffin was, from this moment on, quickly fading from my memory.

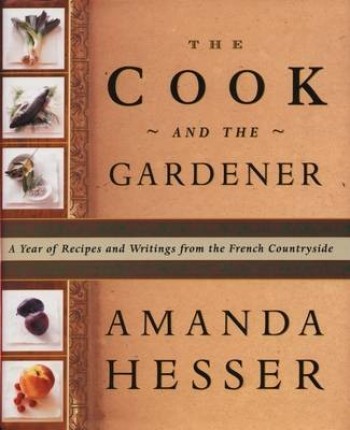

Our turkey’s apotheosis took place when it was ceremoniously placed at the center of our table surrounded by dishes made up as much as possible from vegetables raised on the farm. While the roasted turkey was obviously the piece de resistance, we built around this an assemblage that included a potato, celeriac, onion, carrot, and garlic mash. Our main vegetable, following a wonderful Burgundian recipe from The Cook and the Gardener, was a delicious mix of red cabbage, apples, shallots, and herbs braised for hours in red wine. Our stuffing, a concoction of my own, included (besides turkey innards) chopped fennel, mushrooms, pecans, parsley, crunchy croutons, and, of course, butter. Mark’s pumpkin pie, made from one of our roasted Long Island cheese pumpkins, waited in the wings. It was, however, the turkey that commanded our real attention. As I did my best at ceremoniously carving it, I could not help letting into my consciousness the sense that the way the knife was currently carving up the succulent flesh was so different from the working of the knife in the killing room. But my watering mouth soon overcame any such stirrings in my brain. And Mark and I quickly pulled up our chairs, toasted our thanks, took up our knives and forks, and. with great gusto, set to it. The meat we found was incredibly moist, rich with a subtlety of flavors, and had a lovely texture. The turkey had once again become something else: a delicious mix of gustatory, olfactory, and visual sensations. We looked up at each other mirroring each other’s pleasure, and seemed to have independently arrived at the same conclusion: In all the ten years we had been tasting our own turkeys, this was the best ever. Neither of us had any reservations. Whether it was something to do with how we raised the bird or something to do with how it was prepared, or both, we could not determine, and probably never will. Regardless, the turkey has now entered our memory, and will serve as a future benchmark for all our turkeys. It had become a beautiful memory. True, when I now pass through the empty, desolate turkey compound I still feel saddened by their absence, but I know, yes, I am certain, that they will come again, that in April a small cardboard box will arrive at the post office cheeping with life. And that the whole process will begin again.