Local Immigrant Aid Organizations Prepare for Escalating ICE Enforcement

New Chester New York detention center plans alarm regional advocates.

New Chester New York detention center plans alarm regional advocates.

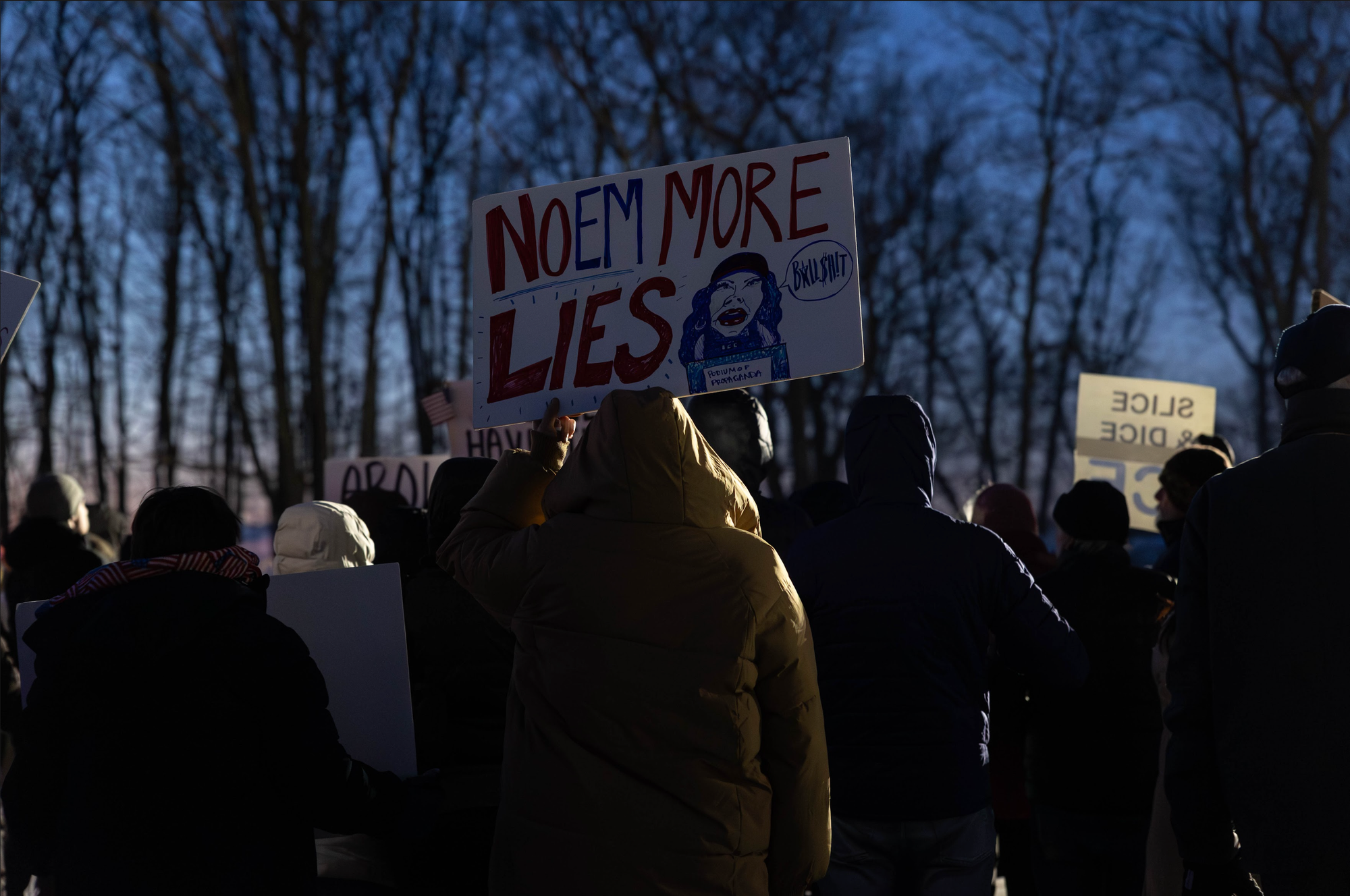

A protester at a rally against the proposed ICE detention center location in Chester New York. Photo by Tony Ramirez, CCSM multimedia organizer.

With eyes on a new ICE detention facility in Orange County, New York, federal immigration agents have made clear their intentions to ramp up activities in the Northeast in the coming months, just in time for the return of economically vital migrant farm workers.

Community leaders say for all those concerned, preparedness is key. “Our community members have been facing this throughout both Trump administrations and even in the Biden administration,” says Bryan MacCormack, executive director of the Columbia County Sanctuary Movement (CCSM). “The killing of Americans by ICE in broad daylight in Minneapolis has opened a lot of eyes.”

MacCormack has been a leading voice in regional immigrant advocacy since co-founding CCSM in 2016. The Hudson based group provides resources and training on how to resist illegal actions by federal enforcement agencies.

Other groups organizing similar initiatives include Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson and Rural & Migrant Ministry in Dutchess County, both of which provide Know Your Rights education, community defense training, and emergency support for families affected by immigration enforcement. In Massachusetts, the Berkshire Immigrant Center (BIC) provides legal services, English classes, and accompaniment support, while BASIC (Berkshire Alliance to Support the Immigrant Community) mobilizes volunteers to maintain a county-wide response network. In northwest Connecticut, the Connecticut Immigrant & Refugee Coalition (CIRC) works with churches and community members in Litchfield County to ensure families know their rights and can access resources quickly if enforcement activity occurs.

“The proposed detention center in Chester is a huge issue right now, that will impact all of our communities, because it will drastically expand the detention capabilities,” MacCormack warns. “Where these detention centers are located increases the amount of ICE activity in those areas.”

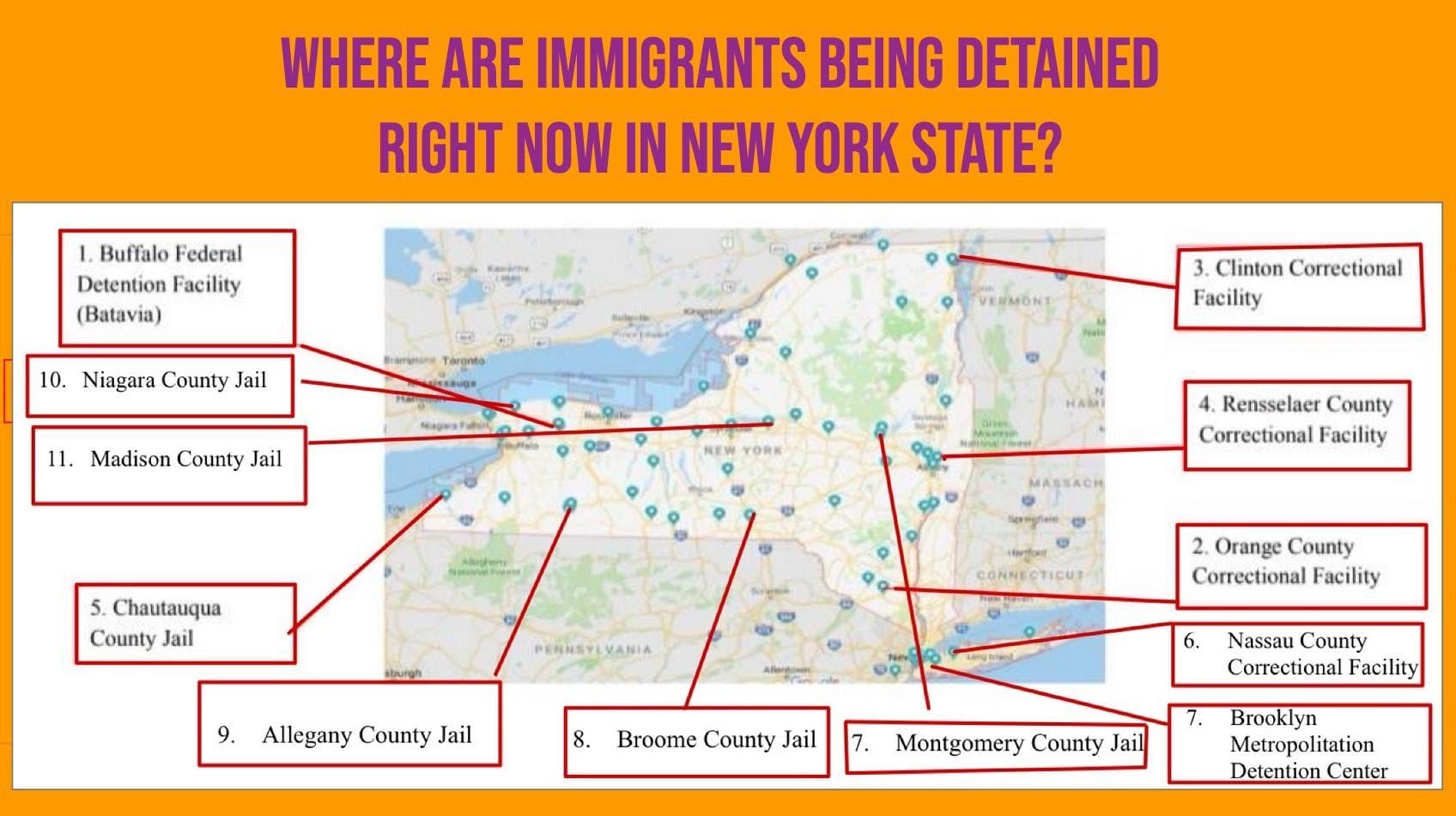

The plan, revealed in late 2025, would convert a warehouse in Chester into a massive processing center with up to 1,500 beds, making it the largest ICE facility in New York State. (By comparison, he notes, the existing federal detention center in Buffalo has about 600 beds.)

The Chester proposal has already sparked fierce local opposition. Community groups—including CCSM, local and state officials, and allies from across county lines—rallied near the site January 30, vowing to block the facility’s implementation.

“Vehicle raids have been the number one form of raids in our region,” MacCormack explains. “That’s been really under-reported.” Instead of targeting homes or workplaces with large operations, ICE agents are pulling people over on roads and highways. Many local detentions now begin with a simple traffic stop.

According to direct accounts and his own personal experiences, McCormack says officers have been profiling drivers by race and by their use of work vehicles – meaning someone driving a construction van, painter’s truck or landscaping vehicle is more likely to be stopped. Oftentimes, he says, these stops do not stem from any prior warrant and are conducted on U.S. citizens without cause. “They call it, ‘collateral arrests,’” MacCormack says.

He adds that these increasingly common vehicle-based tactics have introduced new dangers on roadways but is likely the result of the new reality that immigrants and allies have learned to exercise their rights during home raids—refusing to open doors without a warrant, for example.

“They call it 'Know Your Rights.' I call it 'How to escape arrest,'” Trump border czar Tom Homand said last year.

On the ground, the human impact of intensified ICE activity is already evident. Fear has contaminated daily life for many immigrant residents. “People are not going to work. They’re not sending their kids to school when there’s alleged [ICE] activity,” MacCormack says. Even unverified rumors of an ICE sighting are enough to empty job sites and classrooms. Agricultural employers have told farm workers to stay home on days when a raid is rumored. Parents are keeping children indoors.

The psychological toll of this uncertainty is growing. CCSM reports an increase in mental health issues among their members directly related to the stress of potential raids. The constant threat of being separated from one’s family, or a father or mother suddenly disappearing into detention, weighs heavily on adults and children alike. Not because it could happen, but because it is happening.

“The things that are going on in this country are basically what many of our members fled in their home country,” MacCormack says. Community volunteers working with immigrant families have witnessed spikes in anxiety, depression, and trauma-related symptoms. Local mental health counselors and church leaders have quietly mobilized to provide emotional support.

Amid the climate of fear, something powerful is happening in parallel: ordinary residents are stepping up to protect and reassure their neighbors. MacCormack calls the recent surge of community involvement “miraculous.” Volunteers have formed or joined rapid response networks that mobilize when an ICE sighting is reported.

“The amount of people who are courageously stepping up to defend their communities and do everything within their legal power to document and mitigate the impacts of ICE raids has been absolutely inspiring,” MacCormack says. These networks operate hotline numbers, verify reports of ICE activity, and dispatch trained observers to witness and videotape ICE interactions with immigrants.

Over the past few years, local groups like CCSM have hosted Know Your Rights workshops, free legal clinics, and family preparedness sessions in church basements and libraries throughout the region. These workshops teach immigrants what to do if ICE comes to the door or stops them on the street. One farmworker who attended a training said he now keeps a card by his door with phrases to invoke his rights if confronted. Others have memorized the number of the regional rapid response hotline.

MacCormack also credits allies from all backgrounds who have attended rapid response trainings and learned how to be legal observers, and volunteer for tasks like driving someone to an immigration check-in.

“We can’t be apathetic,” MacCormack says. “The more active and the more prepared you are, the less anxious and fearful you become. When they’ve taken the steps to prepare themselves for the worst, [families] feel more at ease”. It’s not a complete peace of mind, he adds, but it makes a big difference to replace the unknown with a plan.

CCSM and similar organizations also help citizens craft plans and practice what to do during an ICE encounter. “A lot of people want to be out there filming ICE, and they just don’t feel prepared for it,” MacCormack says. “But not everybody has to be responding to active raids. There are so many other ways that people can get involved in the movement,”

Columbia County Sanctuary Movement

Grassroots advocacy and support group based in Hudson, organizing rapid response teams, legal clinics, and family preparedness planning for immigrants in Columbia County and surrounding areas.

Poughkeepsie-based social justice organization that coordinates immigrant defense efforts (including an ICE rapid response hotline) and provides community Know-Your-Rights workshops in Dutchess and other Mid-Hudson counties.

A nonprofit with an office in Dutchess County dedicated to supporting farmworkers and rural immigrant families. RMM offers educational programs, legal referrals, and emergency assistance, and advocates for farmworker rights across the Hudson Valley.

Provides legal services, English classes, and resource referrals to immigrants in the Berkshires. BIC also conducts “Know Your Rights” trainings and has a network of volunteer responders for local ICE activity.

Berkshire Alliance to Support the Immigrant Community

A coalition of Berkshire-area organizations and volunteers that maintain rapid response resources and assist immigrant families during crises. BASIC offers community education on immigration issues and coordinates support across various towns.

Connecticut Immigrant & Refugee Coalition

Statewide coalition based in Hartford that works with local congregations and service providers in northwest Connecticut. CIRC promotes immigrants’ rights, offers guidance on legal resources, and can connect Litchfield County residents with nearby sanctuary churches or aid groups.

A national advocacy organization (based in New York) that offers clear “Know Your Rights” materials and runs an ICE Watch program tracking enforcement tactics. IDP’s guides can help you understand how to respond if you witness ICE activity, and they advocate for fairer immigration enforcement policies.

A national coalition dedicated to exposing and ending the harms of immigration detention. They provide updates on detention centers and toolkits on how communities can campaign against local detention expansion.

The largest immigrant youth-led network in the country, UWD offers grassroots advocacy tools and emergency response training. Their text message alert system and community defense guides are useful for anyone looking to support immigrants’ rights and fight anti-immigrant policies with positive action.