By Dan Shaw

Norman Rockwell’s paintings have become the all-American Rorschach Test. As scholars, collectors and museum-goers reconsider his cultural significance and uncover new layers of symbolism in his work, the artist who lived in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, for 25 years has become an Everyman, a hero to liberals and conservatives, blacks and whites, gays and straights, religious traditionalists and secular humanists. Deborah Solomon’s new, much-discussed biography, American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux), presents him as a latent homosexual, which has not sat well with a few members of Rockwell's family. Nevertheless, if one accepts her premise and then reexamines his catalogue raisonné, the subtext of the artist’s having lived in the closet with forbidden desires emerges as both heartbreaking and, paradoxically, inspiring. It also may explain the depth of feeling evident in his civil rights and social justice paintings of the 1960s. His oeuvre—including “Saying Grace [below]," which sold for $46 million at Sotheby’s on December 4, making it one of the ten most expensive American paintings ever bought at auction

—can be seen as more than a nostalgic evocation of everyday small-town rituals. His work can also be viewed as a chronicle of how homosexuals hid by necessity in the United States prior to 1969 and the dawning of the gay liberation movement. By shedding light on the homoeroticism in Rockwell’s work, Ms. Solomon has opened a Pandora's Box and helped me understand my longtime fascination with the artist. When I first visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, on the weekend after September 11, 2001, I had a visceral response to his paintings. I had wanted to do something patriotic, and his art made me feel proud to be an American in a way that I had never felt before and could not articulate at the time. Like nearly everyone who’s seen his work in person, I was awed by his technique, humor, attention to detail, and the big themes that the paintings often represented. But what impressed me most was his respect for his subjects. Even when he was lightly poking fun at people, his images were imbued with empathy.

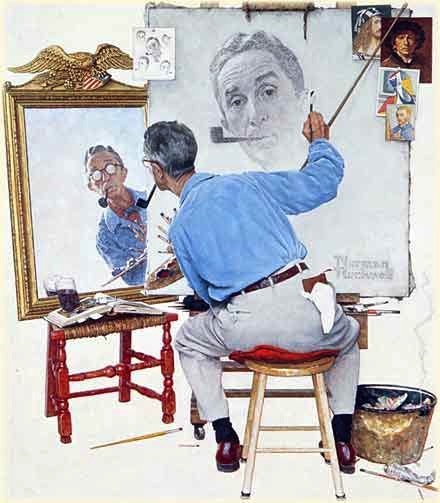

Rockwell was a sociologist with a paintbrush. His depiction of New England folkways was familiar to me from living in the Berkshires, which he called home from 1953 until his death in 1978. He idealized country life, but so do all ex-New Yorkers who live in the Rural Intelligence region. Solomon did not quite grasp this truth: She writes that he “invented the small town that is nowhere in particular," but the world he painted existed and still exists—and not just in Stockbridge. The interactions between ordinary people who look each other in the eye happens every day from Ancramdale and Austerlitz to Wassaic and Williamstown. I thought my feeling simpatico with Rockwell [self, portrait left] was due to our shared yearning for a simpler, kinder world. But then I heard Ms. Solomon speak at the museum in October and read her biography (written with the cooperation of his family). The book portrays Rockwell as an outsider trying to obey the norms and conventions of bourgeois society, which mirrored my own search for acceptance as a gay man in a heteronormative world.

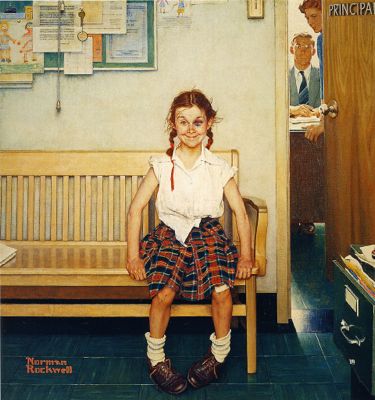

Rockwell’s men are unquestionably more compelling and attractive than his women. He told a reporter from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle: “I can’t draw a pretty girl, no matter how much I try. I’m afraid that they all look like old men." And he explained to the New York Herald Tribune: “If I try to do a picture of a girl with a low-cut dress on, full of allure, she just winds up looking the way you’d want your daughter to look—safe. Or if she’s an older woman she’ll never look like Marlene Dietrich. Every time, she’ll look as though she should be out in the kitchen, peeling potatoes. Sex appeal seems to be something I just can’t catch on a piece of canvas." Instead of femme fatales, some of his women resemble lesbian archetypes. “Rosie the Riveter," the 1943 painting of a patriotic worker in an aircraft factory during World War II, features a butch woman with muscular arms who sits with her legs spread like a man. “Girl with Black Eye" [above] is his 1953 portrait of a heroic tomboy. With scraped knees and unruly braids, she is smirking outside the principal’s office and clearly proud that she’s survived a fistfight.

The discomfort of being perceived as an effeminate male is a recurring theme, too. The 1930 painting “Gary Cooper as the Texan" [left] shows the movie star’s uneasiness as a makeup man applies lipstick to his rugged face. In “Boy with Carriage" from 1916, an adolescent dressed in a suit with a large-nippled baby bottle in his breast pocket is unhappily pushing a stroller. He’s being mocked by two boys in baseball uniforms; his irritation at having to babysit, which was then considered women’s work, is evident on his scowling face. The only way to extrapolate Rockwell’s feelings about sexuality and gender identity is from his paintings. Like most men of his era, he would have never dared express them in letters or journals for fear of possibly being exposed as a deviant (though Ms. Solomon found one diary entry where he described another man on a camping trip as “most fetching in his long flannels").

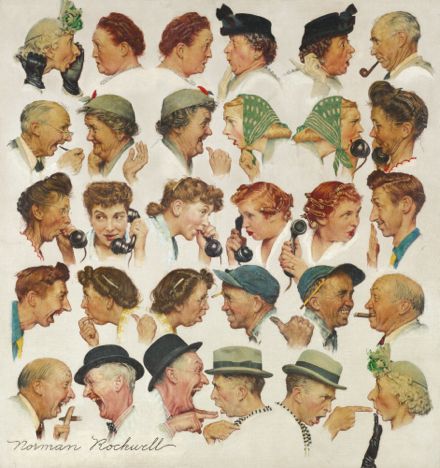

His 1948 painting “The Gossips" (which sold on December 4 at Sotheby’s for $8.5 million) reveals his keen understanding of rumormongering. Although the painting [right] is humorous, it discloses the perils of small-town life where you inevitably know what people are saying behind your back. Looking anew at Rockwell’s work through the prism of forbidden homosexuality, new narratives emerge. Although he had three wives and three children, Solomon portrays him as a loner looking for connection, the repressed gay man conforming to the mainstream. As queer theorists would say, he was hiding in plain sight. (So were other minorities, which is the subject of another new book, Hidden in Plain Sight: The Other People in Norman Rockwell’s America by Jane Allen Petrick, who will be giving a talk at the Norman Rockwell Museum on January 18 at 2 p.m.)

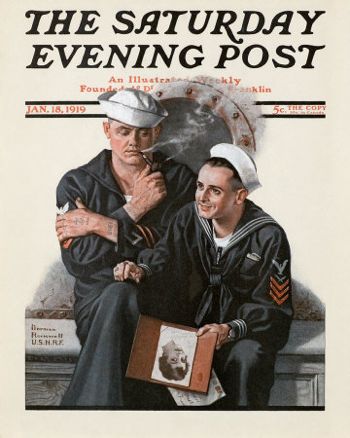

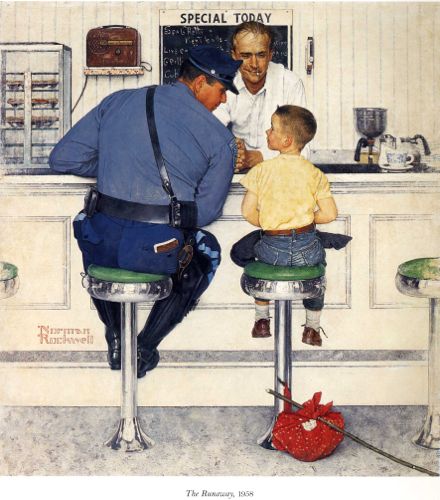

Solomon points out that one of his most reproduced Saturday Evening Post covers, “The Runaway" [left] from 1958, can be read in a variety of ways. It portrays a kindly policeman chatting with a runaway grade-school boy on the adjacent stool at a diner. As Solomon writes, the picture was seen at the time as a “touching tribute to American values." The policeman “represents the warm arm of the law, authority at its paternal best." However, her revisionist interpretation sees the cop “as a figure of tantalizing masculinity, a muscle man in a skintight uniform and boots" who “gazes intently into the boy’s eyes and tilts his upper body toward him." It’s an innocent and benign scene, but the subtext is unmistakable and familiar: I remember being a boy that age and looking at men longingly without quite knowing what those feelings stirring inside of me were. Whether consciously or unconsciously, Rockwell was divulging the unspoken undercurrents of the pre-sexual-revolution era. His 1919 Post cover “Sailor Dreaming of a Girlfriend" [top of page] depicts two sailors side by side with one resting his hand on the other’s knee. Despite its title, the men seem to be daydreaming about one another. Rockwell’s intuitive understanding of what it’s like to feel marginalized and alienated is clear in his civil rights paintings from the 1960s. These overtly political statements proclaim his empathy for African Americans and their striving for full equality and acceptance. If Rockwell indeed spent his life fearful of being outed and thus ostracized by family, friends and a nation who considered him a paragon of American virtue, then he would have implicitly felt solidarity with African Americans who were trying to integrate into an often hostile society.

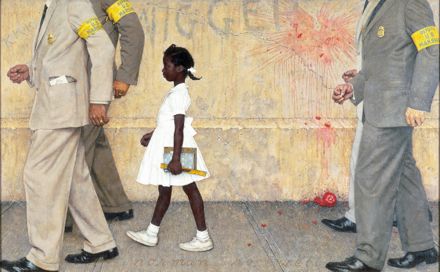

One of his two late masterpieces is the 1964 painting [right] that appeared in Look magazine and was inspired by Ruby Bridges, the six-year-old girl who was the first African American to attend an all-white school in New Orleans in 1960. She is shown walking to school with pride and courage, escorted by four U.S. Marshalls. There’s evidence that rotten tomatoes have been thrown her way and splattered on the wall behind her where the N word has been scrawled. Ms. Solomon calls it “the defining image of the civil rights struggle." Its pathos is undeniable, and when I saw it for the first time it brought tears to me eyes. Interestingly, the painting is called “The Problem We All Live With." Was Rockwell merely suggesting that racism was a social issue for the entire country? Or was he implying that every individual lives with a fear about being bullied, ridiculed or hated? Did he identify with the African American girl who needed bodyguards just to go to school like everybody else? Ruby Bridges, c’est moi?

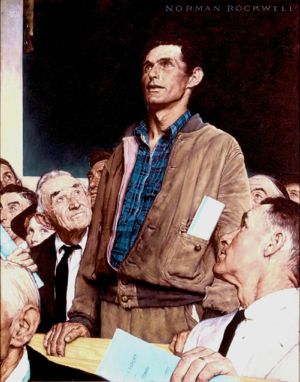

Certainly, a boy or girl who identified as gay in 1964 would have been treated just as cruelly. After all, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not include any mention of sexual orientation. Gay rights were a nonissue then, and it’s possible that Rockwell was projecting his own fears and hopes onto Ruby Bridges. From a queer perspective, Rockwell’s 1943 “Freedom of Speech" [left] takes on new significance, too. Ms. Solomon suggests that the swarthy, working class man (as evidenced by his clothes) who’s not wearing a wedding ring and standing up to speak surrounded by WASP men in jackets and ties could be an immigrant, a literal outsider. While the painting ostensibly celebrates the inclusive, democratic spirit of a New England town meeting, it can also be read as a gay man’s wish to stand up and be heard: The freedom to be.

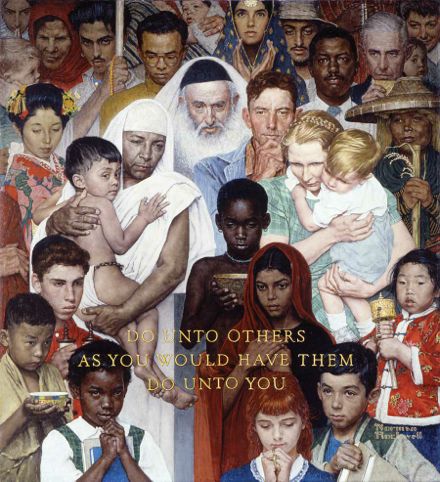

Rockwell’s other late masterpiece is the “Golden Rule" [right] from 1960. He imagines an egalitarian world where all people are accepted for who they are. (A mosaic copy of the painting is displayed at the United Nations.) Predating by decades Bob Geldof’s “We are the World" music video and the United Colors of Benetton campaign, “Golden Rule" is a utopian, multicultural tableau where people of all races and ethnicities live in harmony. The words “Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You" are painted in gold right on the canvas. The phrase would be especially poignant for a man who lived in a society where the Golden Rule did not apply to homosexuals. Today, Rockwell can be seen as the accidental activist who advocated for equality the best way he could without jeopardizing his reputation, friends and family. Did he have any other choice? Ultimately, he was more than an extraordinarily gifted and influential artist. He was a great humanitarian, too. Dan Shaw, the co-founder of Rural Intelligence, is a regular contributor to The New York Times. He is writing a book on life in the closet.