Photographer Stephen Shore presents "Early Work" at Oblong Books

Shore's new book, "Early Work," takes us back to New York City in the early 1960s

Shore's new book, "Early Work," takes us back to New York City in the early 1960s

Stephen Shore has lived in the Hudson Valley for decades, but his new book, Early Work, takes us back to New York City in the early 1960s, when he was a teenager with a Leica and an unerring sense that photography would be his life. Most of these pictures, unseen for more than half a century, now surface as both a record of youth and an unexpected prelude to an influential career in American photography.

Shore insists he doesn’t remember taking most of them. “Two thirds of the pictures—when I saw prints of them, they were as new to me as they would be to you,” he says. What he does see, looking at them now, is the emergence of a sensibility. “From the very beginning, there is an understanding that a camera doesn’t point, it frames. There’s always an understanding of the importance of the frame in the picture, that what the photographer is doing is filling the frame.”

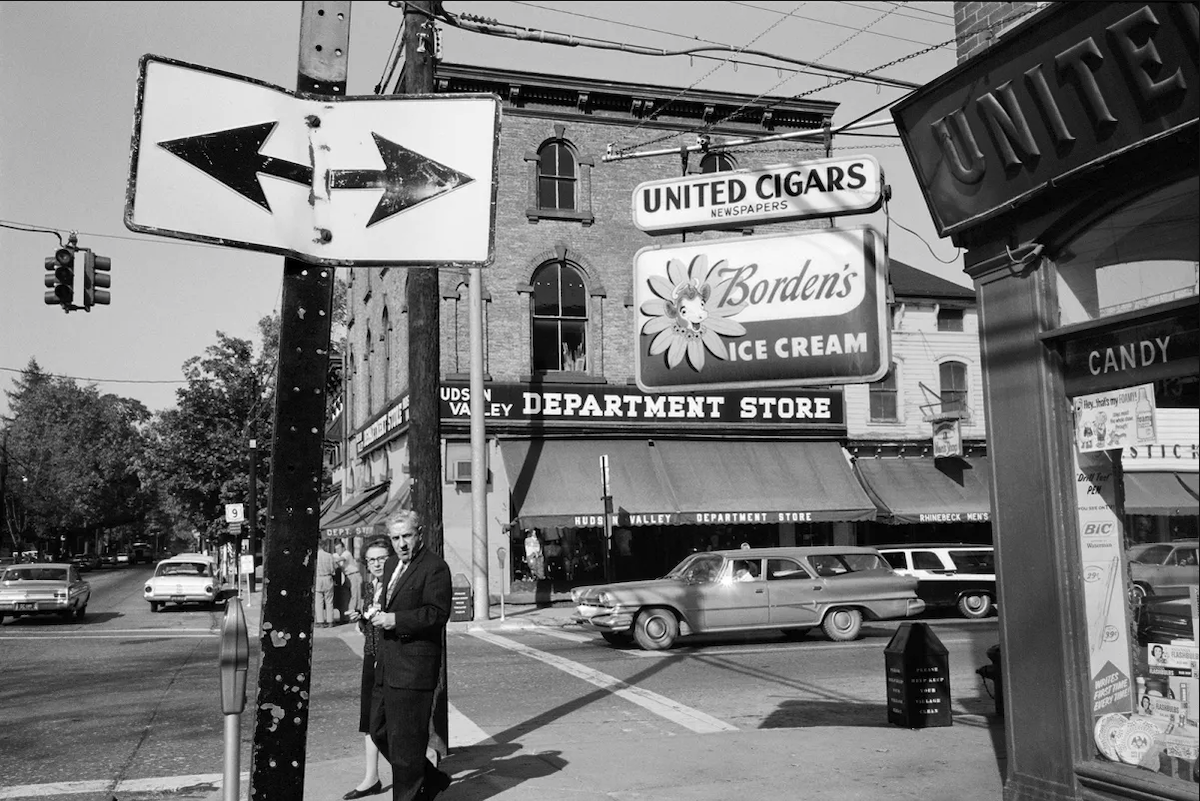

A photo from the early 1960s by Stephen Shore from his new book, Early Work. Shore's parents are pictured on the corner of Market Street and Route 9 in Rhinebeck. Credit: © Stephen Shore. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York and Sprüth Magers

That distinction—between pointing and framing—becomes the foundation of Shore’s work. Pointing, he explains, directs attention like a finger at a teapot. But in a photograph, “there is equal attention throughout the entire frame. What’s in the corner is as important as the teapot, even though the teapot is the subject.” It’s the equal distribution of attention across the rectangle that marks Shore’s style, from the black-and-white Early Work through his pioneering color exhibitions “American Surfaces” and “Uncommon Places” in the early 1970s, which transformed roadside diners and motel beds into the subject matter of high art.

On a bright day in the early 1960s, a teenage Shore photographed his parents on the corner of Market Street and Route 9 in downtown Rhinebeck. The frame captures them paused at the crosswalk beneath a clutter of commercial signage—United Cigars, Borden’s Ice Cream, Hudson Valley Department Store—while a pair of classic cars cruise past. The image feels both ordinary and uncanny, a slice of small-town life now fossilized in silver gelatin.

For Shore, rediscovering the picture more than 60 years later was startling. His studio manager, Laura Steele, had unearthed it while scanning old negatives. “When I look at that picture, I’m looking at the signs, I’m looking at the relationship of signs to buildings, and I’m seeing that I’m positioning myself so that if I were to step a foot to the right, it would fall apart. If I took a foot to the left, it would fall apart. And this is exactly the kind of thinking that I explored in depth later, in the 1970s.”

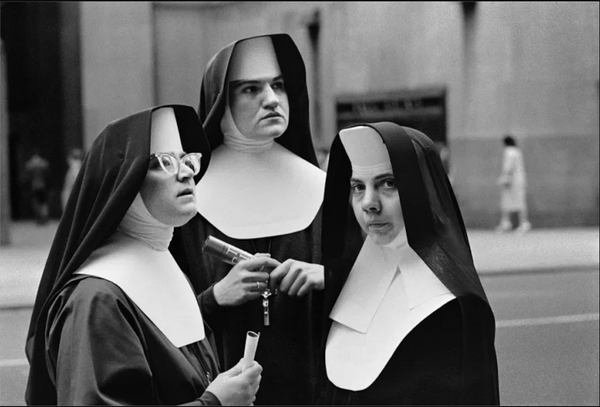

A photo from Stephen Shore’s Early Work, featuring photos taken from 1960-1965.

Chance, memory, and vision braid throughout Shore’s career. At age 10, a neighbor gave him a copy of Walker Evans’s American Photographs. Soon after, Edward Steichen bought three of his prints for the Museum of Modern Art when Shore was 14. By 17, he was haunting the Factory with Andy Warhol, photographing an art world in full swing. Shore’s later work—deadpan color studies of America’s vernacular landscapes—secured his place alongside William Eggleston and Joel Sternfeld as one of the photographers who legitimized color in fine art

Yet Shore resists easy mythmaking. He is candid about the strangeness of revisiting work he barely remembers making. He is equally frank about teaching at Bard College, where has been the program director of the Photography Program since 1982. (Shore lives in Tivoli.) As an instructor, he has seen students arrive with a vision that can’t be taught. “Every year there are some students—I will see instantly that there is a real depth to their vision. It’s magic.”

That innate spark still puzzles him. “As soon as I went into my makeshift darkroom when I was six, I knew that I was a photographer,” he says. “But I don’t know where it comes from.”

Even as he looks back, Shore is also looking forward. Our conversation detoured into artificial intelligence, which he has been experimenting with as a research tool. Shore described feeding the AI assistant Claude with critics’ writings and his own, asking it to analyze photographs. “It is amazing,” he says. “I use it as a research tool. Sometimes it’s clear to me it is thinking. It is not repeating what other people are saying. It’s making connections.”

A photo from Stephen Shore’s Early Work, featuring photos taken from 1960-1965.

But when it comes to AI-generated art, Shore is skeptical: “When I see art produced by AI, it reminds me of a third-rate art fair,” he says. “The work in the booths looks just like art. If you didn’t know any better, you would think it is art. If you want to put something over your couch, it looks like art. If you’re decorating a corporate office, you could put it up. But there is something else that happens in art. There is an aliveness there. There is a tapping of something deep in human nature that some works of art transmit. And I have yet to see that in anything AI has produced.”

The aliveness of Shore’s work—whether in a Rhinebeck street corner or gritty New York City scenes—is what makes it endure. Early Work gives us the startling image of a fully formed eye emerging in adolescence, already attuned to the relationships within the frame, already alive to the gap between the world and its translation into a photograph. A reminder that vision can arrive early, whole, and insistent.

Stephen Shore will discuss Early Work at Oblong Books in Rhinebeck on September 11 at 6pm. Admission is free. Pre-registration is recommended.