Rituals, Talismans, And Divination: Artists Search For Meaning In “Like Magic”

The artists in MASS MoCA’s latest exhibition combine technology and magic in ways that reflect a belief system.

The artists in MASS MoCA’s latest exhibition combine technology and magic in ways that reflect a belief system.

Cate O’Connell-Richards, “Flail Broom,” 2022, brass, red brass, wood, broomcorn, twine, hemp. Photo: Kaelan Burkett

I’m always fascinated to learn what people turn to for comfort, care, and existential meaning.

Religion — or the belief in a higher power — is a source of reassurance for many, and countless objects are used across practices to express and fortify that connection. A Catholic crucifix is a reminder of God’s love. Tibetan prayer flags contain Buddhist mantras that spread peace, compassion, and good fortune. Kippot, kufis, and Mormon temple garments are worn to convey piety. Beads are used in many religions to guide prayer, and gemstones themselves are thought to have healing properties. I remember placing an emerald and aquamarine crystal over my heart when I was pregnant with my daughter to ward off a brewing cold. (It worked. Rather, I awoke the next morning feeling fine, for whatever reason.)

It’s not these belief systems specifically but the practice of ritual itself that is investigated in MASS MoCA’s latest group exhibition, “Like Magic.” On the contrary, mainstream religious practices are mostly absent here. Instead, curator Alexandra Foradas gathered the work of ten contemporary artists who, she says, have structurally been denied power due to their race, sexuality, gender identity, indigeneity, or immigration status. Laws governing organized systems often demand uniformity, creating “othering” experiences for those who advocate against, or at the very least, question those systems.

“Magical” practices ensue.

Installation view of “Like Magic” at MASS MoCA, North Adams, Mass. Photo: Kaelan Burkett

Witchcraft may first come to mind for New Englanders. In the 17th century, witch hysteria fueled by sexism, racism, classism, and religious extremism led to the executions of more than a dozen people in colonial Massachusetts and Connecticut. “Like Magic” artist Cate O’Connell-Richards, a queer artist, jeweler, and broomsquire, takes control of this narrative by transforming the language and tools of witches into exquisitely crafted objects including rings, candlesticks, and harnesses outfitted with “witch-enhancements” meant to heighten a sexual experience.

Brooms, a ubiquitous object of labor also associated with witches’ magic, become weapons, spears, and totems to be reclaimed in new rituals. “Craft-informed artists deal a lot with process, and [we] have to find joy and meaning in that,” O’Connell-Richards says. “It’s not about an end point — it’s about working to become a more connected person.”

Mundane objects imbued with ritualistic meaning abound in “Like Magic.” Iran-born artist Gelare Khoshgozaran‘s luminous installation “U.S. Customs Demands to Know,” a collection of shipping boxes sent from Iran that were opened and searched by Customs and Border Protection officers, and Rose Salane’s powerful pairing of lost rings alongside photographs of artifacts stolen from and subsequently returned to the Pompeii archaeological site redefine and personalize the nature of sacredness. Grace Clark presents multiple works — including “Lean,” an arrangement of salvaged, whittled, broken, reshaped, and mended wood —that document her search for healing in life and solace from death; her piece “In a new light (Healing Dirt)” invites others to do the same.

“…I tried to open my hopeless heart to anything that could help me: maybe God, nature, my own public claim, or my belief,” Clark says in conversation with Foradas as published in the “Like Magic” gallery guide. “In that choice, I didn’t find a cure. But I did find, within myself, a little higher power.”

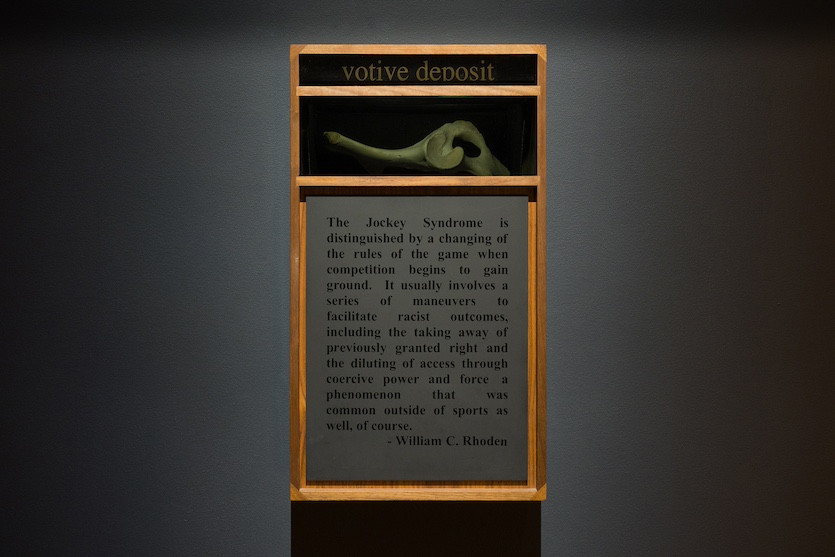

Nate Young, “Votive Deposit,” 2019, walnut, horse bone, plexiglass, gold leaf, spray paint, LED. Photo: Kaelan Burkett

Chicago-based artist Nate Young is also searching for healing and connection to his ancestors, but within a constant time loop of racial trauma. His meticulously built reliquaries enshrine — and, thus, protect, honor, and elevate —the bones of the horse his enslaved great-grandfather rode to freedom on and later killed for his own protection. The literal darkness that envelopes these objects transforms the gallery into a chapel-like space, with a pitch-black installation in the middle of the room serving as the confessional, depriving you of all senses except for what you can think, hear, and feel.

As in many religions and religious practices, performance is an important component to the themes in “Like Magic” as well as the personal belief systems of several participating artists. Singing, dancing, listening, chanting, reading, praying, walking, and touching are highly emotional expressions of faith, particularly in times of uncertainty or need.

New York City-based filmmaker Tourmaline and multidisciplinary artist Simone Bailey each present performance as video documentations that position the viewer as audience. Tourmaline’s short film “Atlantic is a Sea of Bones” and Bailey’s “Hometraining” video installation use pageantry to make new meaning of the past, specifically as it relates to Black Americans and enslaved Africans.

Installation view of Petra Szilagyi, “Bless Your Hard Drive,” 2021–2023. Mixed media. Courtesy of the artist. Made with MASS MoCA. Photo: Kaelan Burkett

Artists Raven Chacon, Petra Szilagyi, and Johanna Hedva, on the other hand, invite the viewer to become the performer in their work. Chacon’s musical scores provide us with unique sets of instructions —informed both by Navajo traditions and conceptual art —that challenge the conventions of how and what we learn. Szilagyi invites us to “pray however to whatever” inside their cob hut and Hedva asks us to both read and listen to their short story “Who Listens and Learns.” Both of these nonbinary artists explore the magic and mysticism of binary code, the internet, and artificial intelligence —which could become our new God.

“Like Magic” is on view in MASS MoCA’s building 4.2 now through August 2025.