Six Senses Looks to Change Narrative on Controversial Clinton Resort

The all-consuming civic concern has pitted neighbor against neighbor.

The all-consuming civic concern has pitted neighbor against neighbor.

For more than three years, the proposal by Six Senses, a global wellness-resort brand owned by the multinational hotel group IHG, to build a retreat center in the Town of Clinton has divided the Dutchess County community. What began as a localized land-use dispute has expanded into a broader political, legal, and philosophical fight over corporate trust, environmental stewardship, and the autonomy of small towns.

Now, after a series of lawsuits, a surprise intervention by the neighboring Town of Rhinebeck, and election maneuvering that complicated local races, Six Senses is attempting a reset of its public perception. The company has begun speaking more openly with the press, invited conversation with former opponents, and dispatched its former global CEO, Neil Jacobs, to explain why residents should believe the project aligns with the community’s values.

Opposition remains. Lawsuits remain. Mistrust remains. But the narrative has undeniably shifted, most notably because one of the project’s most influential early opponents, Dal LaMagna, now supports the development. LaMagna was one of the architects and primary funders of the grassroots Stop Six Senses campaign, now called Common Sense HV. “I’ve changed my position regarding Six Senses,” he says. “These are probably the best people to develop the property we could ask for.”

As with most Hudson Valley development battles, both sides offer persuasive arguments, and none of the questions have simple answers.

A Conflict Years in the Making

Six Senses purchased the 236-acre former equestrian center and quasi-legal event venue in Clinton in late 2022. The site includes an indoor riding arena, barns, residences, a dining building, and other structures. According to Mike Palumbo, an IHG executive overseeing the development, the company moved forward only after a Clinton zoning official, who later had to recuse himself from the process due to ties to the previous owner, confirmed that the property’s special-use permit designating it a conference center remained valid.

“We checked with the municipality, we met with the planning board,” Palumbo said during a recent tour. “The zoning person wrote us a letter saying the special-use permit was active.”

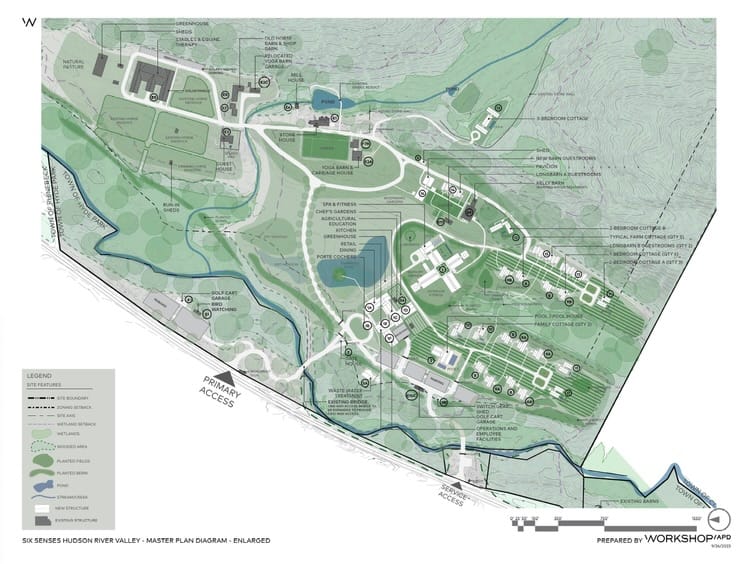

The proposed retreat center would expand the existing facility while, according to Six Senses, maintaining a low visual profile. Lodging would grow from 15 units to 65 dispersed accommodations integrated across the site. Plans include a roughly 21,000-square-foot wellness complex composed of several small buildings rather than one dominant structure. The dining facility would be enlarged to support programming rather than operate as a large public restaurant. Palumbo said the company purposely avoided vertical construction: “We’re trying to keep everything smaller.”

Programming is expected to include equine therapy, yoga, detox retreats, and other wellness offerings. Palumbo emphasized the property would not be an all-inclusive resort; guests would pay separately for meals and services, and the company expects many will venture into surrounding communities like Rhinebeck.

The current fight is rooted in a 2021 amendment to Clinton’s zoning code that created a narrow pathway for “conference centers”—hospitality uses permitted in certain rural/agricultural districts only if they provide a curriculum of classes and meet other criteria. Critics argue the provision created a loophole that allows hotels where they would otherwise be prohibited.

Real estate developer and Clinton resident Graham Trask, who lives part of the year near the project, has become one of the central organizers of the opposition. He says his experience battling a hotel in his South Carolina hometown shaped his perspective on Six Senses.

“While I’m a real estate developer, and while money is good and all that, I was not prepared to blow up our golden goose of a historic town to allow a Marriott hotel in the middle of it,” he said, noting parallels in Clinton: a lucrative hotel plan, a sensitive rural landscape, and pressure on local officials. Trask and his father are currently being sued for $120 million by that South Carolina hotel developer for alleged interference.

Trask is now president of Common Sense HV and helped launch Save Clinton, a town-focused group targeting the conference center law specifically. “The violation of the intent of our zoning law to, in effect, allow a hotel in our most sensitive and rural zoning districts is ridiculous,” he says. Calling the project a conference center he adds, “is such a crock. It makes me want to vomit.”

LaMagna, whose property shares a mile-long border with the Six Senses site, still insists the town must negotiate firm agreements on taxes, environmental conditions, helicopter bans, and trail access, but he now sees those agreements as achievable and preferable to years of litigation. His reversal has caused friction with neighbors who he says accuse him of being “paid off.” LaMagna, founder of the Tweezerman self-care brand and a longtime political activist, laughs off the notion. “I don’t need their money. I’m the Tweezerman.”

Environmental concerns continue to animate much of the organized opposition. Members of Common Sense HV have raised alarms about wetlands, wildlife habitat, water supply, noise, traffic, and the potential impact on Browns Pond.

The company argues that environmental review has been extensive. Palumbo says wetlands were professionally surveyed and mapped, and that the DEC confirmed buffer zones. “We’re not building within the buffer zones,” he says, adding that the project avoids the northern section of the property stretching toward Browns Pond.

LaMagna noted in his analysis that 153 acres of the property are enrolled in a state forest-conservation program, making development on that land cost-prohibitive. He emphasized that Browns Pond “will remain off-limits—no dock, guest access, or nearby construction,” and that only about 36 acres of the 236-acre parcel are slated for development.

The most contentious environmental issue, however, is the access road. The project sits almost entirely in Clinton, but the only viable entrance crosses a small section of Hyde Park. To avoid a dual-municipality approval process, Hyde Park passed Local Law 1, asserting a town cannot regulate land use on property outside its borders simply because an access point passes through it.

Common Sense HV is suing to overturn the law, arguing it was written to benefit Six Senses. In an unexpected move, the Town of Rhinebeck joined the lawsuit, as the property abuts that municipality as well. LaMagna has acknowledged that overturning the law could block Six Senses entirely. The case is pending in Dutchess County court.

Rhinebeck town board member Dana Peterson said the issue is of great importance to her town because making exceptions to allow spot zoning in the Hyde Park environmentally protected greenbelt district creates inroads for the type of un-thoughtful planning that allowed Hyde Park’s southern end to devolve into a series of strip malls to encroach further up towards Rhinebeck.

“When we do something major we take our time and make sure it follows the law and conforms with our comprehensive plan. Good thing’s come out of that.” Peterson said, noting that Rhinebeck has approved major lodging projects, but they sit within areas of appropriate zoning.

“I have nothing against high-end resorts,” she continues. “I think there are people who are against this project because of socioeconomic disgruntlement. That’s nothing to me. There just needs to be a thoughtful review. There needs to be a negotiation. If Clinton is going to make an exception for Six Senses they at least need to negotiate conditions and get something in return.”

This year, the Six Senses proposal moved from the planning board to the political arena when Save Clinton attempted to reshape the Town Board through endorsements of a Republican slate that pledged to repeal the conference center law. While margins tightened, the effort ultimately failed: Democratic Supervisor Michael Whitton and council member Eliot Werner retained their seats.

Rhinebeck’s involvement in the lawsuit has created political fallout there as well. This fall, according to sources with knowledge of the undertaking, Rhinebeck Area Chamber of Commerce president and owner of Market St. restaurant Luciano Valdivia and real estate broker Wendy Maitland—who represented the seller in the Six Senses transaction—began an anonymous campaign encouraging residents to write in Village Mayor Gary Bassett for Town Supervisor. Their target was incumbent Supervisor Elizabeth Spinzia who, along with the entire town board, supported Rhinebeck joining the lawsuit. The write-in effort did not affect the race but has caused intense tension in local political circles.

Six Senses management argues Rhinebeck businesses have legitimate economic interests at stake, as they are the closest commercial center to the project.

Another source of skepticism about Six Senses is corporate trust. In a town with no existing hotels, the prospect of a multinational hospitality conglomerate establishing a foothold can feel jarring.

Opponents question how they can trust a company that operates under IHG. They point to the Six Senses–branded residential tower rising in Dubai—the tallest of its kind—where human-rights groups allege the construction firm hired by IHG uses labor practices consistent with modern slavery. IHG has also faced criticism for developments in a western region of China where Uyghur Muslims have been subject to mass detention, forced relocation, and worse.

Jacobs, who led Six Senses for nearly three decades, addressed these concerns directly. Navigating worker-rights issues in Dubai, he says, is “complicated,” acknowledging that while Six Senses and IHG have been consistent leaders in lodging industry anti-slavery efforts, “we have limited control over construction practices,” he says. “I understand why people raise concerns.”

Still, Jacobs emphasized that the Clinton retreat reflects the brand’s core principles. “Look at the 29 hotels,” he says. “All are low-rise, low-density, and respectful of the land.” He noted that IHG grants Six Senses unusual operational independence. “We don’t want to be in any community where people don’t want us,” he said, though he also believes the company is legally entitled to proceed.

The Core Question

Strip away the legal filings, political intrigue, and international scrutiny, and the heart of the dispute becomes clear: Many residents see the Six Senses proposal, however carefully designed, as too drastic a change to the town’s fundamental rural character.

Supporters say the tax revenue and job creation could benefit Clinton without altering its identity. Opponents argue that once a multinational corporation is established, the potential for expansion or change in use remains real, regardless of current promises.

Jacobs notes that the company has abandoned projects in the past due to community opposition. One was in Brazil and another on an island off the South Carolina coast. But Jacobs believes it is unlikely Six Senses would leave Clinton, as he says the project is “approved under existing law.”

LaMagna summarized the quagmire. “People fear big corporations, and that’s a reasonable fear,” he says. “But I also think people can get locked into their positions. We need to find a way for the town to protect itself while also letting something good happen.”