“Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints” Opens At Williams College Museum Of Art

The exhibit is the first comprehensive survey of LeWitt’s printmaking practice and follows the trajectory of his career.

The exhibit is the first comprehensive survey of LeWitt’s printmaking practice and follows the trajectory of his career.

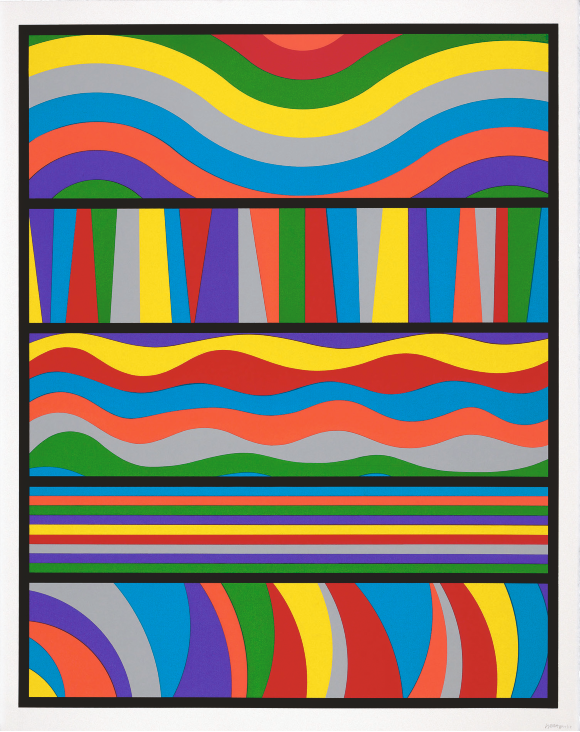

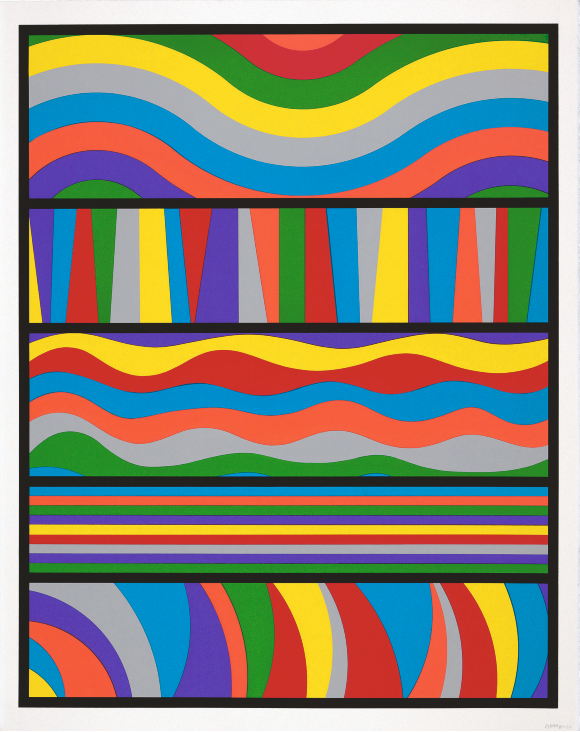

Sol LeWitt, Lincoln Center Print, 1998. Screenprint, image 35-1/2 x 28 inches. LeWitt Collection, Chester, CT

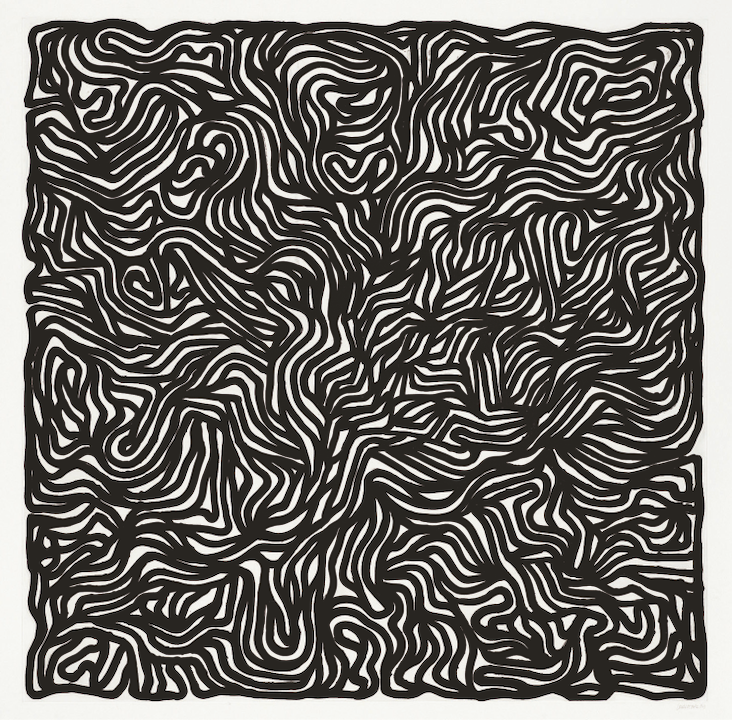

For someone who is familiar with the conceptual artist Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) only through his wall drawings at MASS MoCA, “Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints” currently on exhibit at Williams College Museum of Art in Williamstown, Massachusetts is a window into what the artist was doing before, during and after he was creating the instructions for the wall behemoths. For those, you have to stand back to take them in. At “Strict Beauty,” the inclination is to come close, to examine the intricate lines, arcs, circles and grids that make up so much of LeWitt’s output. The exhibit is also an exploration of the many mediums he worked in: lithographs, silkscreens, etchings, aquatints, woodcuts, and linocuts. Curated by David Areford in partnership with the New Britain Museum of American Art, the show contains more than 200 prints spanning LeWitt’s career.

During a press preview to tour of the exhibit, Areford, Professor of Art History at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, assured the group that although LeWitt’s geometric ourvre would have you believe the artist was cool, intellectual and detached, he was anything but. He was, however, full of contradictions. The ehibition opens with works from 1949, a collection of LeWitt’s earliest prints figures and scenes of urban life. As an art student at Syracuse University in the mid 1940s, LeWitt was introduced to printmaking — in particular, lithography. His style was a mix of realistic and sometimes expressionistic, and it was these early works that brought him his first official artistic recognition. Winning a large cash award from the Tiffany Foundation allowed him to drop out of an MFA program and take his long-awaited, lifechanging trip to Europe. Upon his return, he began his artistic life in New York City.

Sol LeWitt, Whirls and Twirls (Color), 2005. Linocut, image 15-7/8 x 47 inches. New Britain Museum of Art

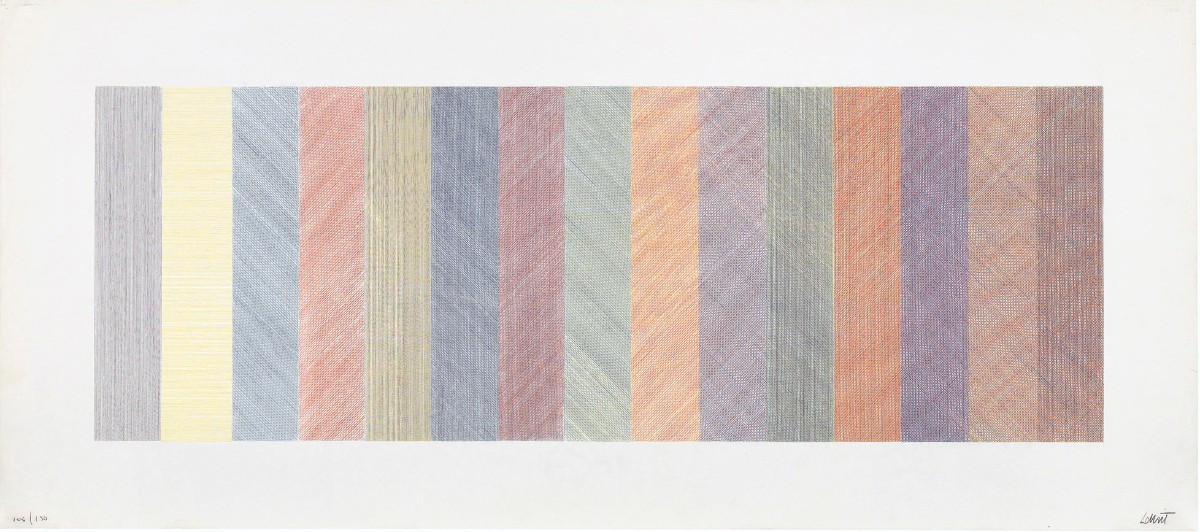

Here is where he developed his distinct geometric and linear formal language, the recognizable Sol LeWitt. In his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967) — regarded as the “first manifesto of conceptual art” — he championed an art in which “ the idea or concept is the most important aspect.” He would rely on a preset plan, with the motivating idea being that the production of the image would ultimately realized by others, i.e., drafters and printmakers. By 1971, with his “Bands of Color in Four Directors & All Combinations,” a set of 16 color etchings, he had developed his signature motif and genetic structure for nearly all of his art. Like he did in so many of his future works, LeWitt provided the initial etchings, and then turned them over to a master printer, who proceeded with the mechanical process of producing the prints.

The exhibit follows LeWitt’s trajectory and exploration in four thematic sections, moving from “Lines, Arcs, Circles, and Grids,” to “Bands and Colors, “From Geometric Figures to Complex Forms,” and “Wavy, Curvy, Loopy Doopy, and in All Directions.” By the 1990s, says Areford, the artist had loosened up his own rules. LeWitt’s fixed lines and bands, devoid of descriptive or expressive character, have been replaced by bright colors and wavy, zigzaggy bands. LeWitt loved classical music, particularly Bach and Mozart, and his poster for Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival was a turning point; the movement and rhythm of the bands reflect a visual musicality that evokes a response that’s more visceral than ones for the disciplined lines of his earlier work.

During his final 15 years, LeWitt’s works turned bold and sensuous, hence the “wavy, curly, loop doopy” (his words) images. These are the most painterly of his prints, says Areford, created through a complex silk-screening method involving quarter or half turns of each print matrix. The result is an intricate weave of layers, colors and brushstrokes that beg for proximal viewing.

According to the Williams College Museum of Art, “Strict Beauty” is the first comprehensive survey of the conceptual artist’s printmaking practice. Many of his early lithographs have never been publicly seen until now. While we have experienced LeWitt’s distinct geometric and linear language painted on the walls of MASS MoCA, it is a treat to follow his development of that language in prints up close and personal.

“Strict Beauty: Sol LeWitt Prints” runs through June 11.