The Cost of a Child's Life: Grieving Hillsdale Parents Say They're Ignored by State Law and Governor Hochul

After a tragic and preventable loss, a local farm family is fighting for systemic reform.

After a tragic and preventable loss, a local farm family is fighting for systemic reform.

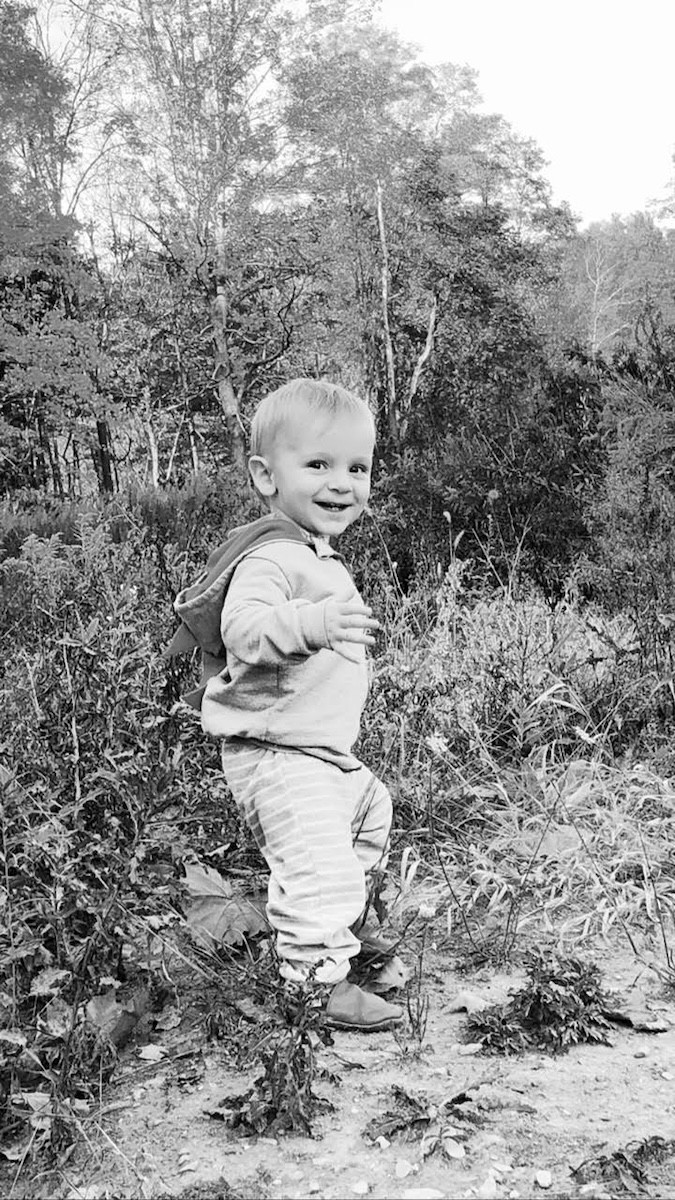

Micah and mom Keri-Sue McManus.

The past three years have been an agonizing journey for Keri and Dan McManus. In November 2022, their three-year-old son Micah died while they desperately sought the medical care he needed. His death, which they attribute to medical negligence, has set them on a new mission; justice for Micah and peace for themselves.

As they pursue a medical malpractice lawsuit against Albany Medical Center and individual healthcare providers, the McManus family, proprietors of Common Hands Farm in Hillsdale, is also fighting for the passage of the Grieving Families Act—a bill that would modernize New York’s wrongful death statute, allowing families to seek damages for emotional suffering rather than limiting compensation to economic losses.

The bereaved can receive compensation for the loss of a breadwinner in New York, but a child, or a stay at home parent, is worthless. Despite receiving overwhelming bipartisan support in the state legislature, the Grieving Families Act has been vetoed three times by Governor Kathy Hochul, including on December 21 of last year. New York and Alabama are the only states without such a statute. The McManuses say fighting for the bill has nothing to do with money, it’s about accountability and prevention.

Micah’s death was the culmination of what his parents describe as repeated failures of the healthcare providers. According to their attorney, Joseph Caiccio, Micah was brought to Albany Med multiple times with troubling symptoms following a bout with Covid-19, only to be misdiagnosed and discharged. Keri brought him to doctors six different times, her concerns even dismissed by the boy’s primary pediatrician. On November 30, 2022, at Albany Med for the third time, after hours of delayed intervention, he died from a pulmonary embolism caused by blood clots that had formed in his liver.

Today, holding back familiar tears, Keri recalls her frustration while pleading for her son’s care. She says she repeatedly sought tests that were ignored or dismissed. “I tried so hard to advocate for him,” she says. “I didn’t feel like anyone was listening to me. And after he died, the hospital never followed up. They never apologized. We were just gone from their sight.”

An harrowing and comprehensive article on the McManuses ordeal was published in The Guardian last year. In the United Kingdom and other countries with socialized healthcare there is an independent investigation done during wrongful death claims, something the McManus family believe should be adopted here as well. Dan says Micah was immediately forgotten by the hospital. When relatives went to retrieve his body the day after his passing, there was a long moment of confusion when staff weren't sure where Micah was.

Albany Med has been under significant scrutiny for years for some of the longest wait times in the country and staffing shortages. Nurses and other staff continue to advocate for improvements. “We support the hospital workers that are fighting for better conditions there,” Keri says. “But we were there and so many people had the ability to help us but they didn’t.”

In the aftermath the family returned to the farm and got back to work. Along with running Common Hands, its popular CSA and farmers’ market stands, Dan is also a skilled stone mason. They also went back to being parents to their younger daughter, and Keri had another child last April, a baby girl. But the trauma of losing Micah, in a way they believe could have been avoided if providers had just listened to them, remains a shadow over their lives. You can see it in their eyes. “He was just so good.” Keri says, welling up again. “Even now, It still doesn’t feel real.”

On the second Sunday of each month The McManuses hold a death cafe at the farm where people dealing with loss come together to share their stories and try to heal together.

Advocates for the passage of the Grieving Families Act, like those at the Trial Lawyers Association say the repeated vetoes of the bill can be attributed, in part, to significant lobbying efforts by influential medical and insurance industry groups. The Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA), a powerful entity representing over 280 hospitals and health systems, has been a vocal opponent of the bill. GNYHA argues that expanding the scope of wrongful death claims to include emotional damages would lead to increased liability costs, which could, in turn, result in higher insurance premiums and financial strain on healthcare facilities—an argument echoed by Hochul in her veto.

“While well intentioned, these changes would likely have resulted in higher costs to patients and consumers, as well as other unintended consequences,” says Hochul in her post veto memo. The governor’s office did not return multiple requests for comment. “For the third year in a row the legislature has passed a bill that continues to pose significant risks to consumers, without many of the changes I expressed openness to in previous rounds of negotiations."

Critics, who are already working on reintroducing the bill, argue that this reasoning is based on a false premise. “If 48 other states have figured this out, why is New York incapable of doing the same?” asks Sabrina Rezzy of the Trial Lawyers Association. She points out that the actuarial predictions used to justify Hochul’s decision were conducted by firms directly tied to the insurance industry. “The same firms predicted that past wrongful death reforms would cause massive premium increases—and they were wrong. In Illinois, for example, after similar reforms, premiums remained stable or even decreased.”

The political influence of the medical and insurance industries over Governor Hochul’s administration is another area of concern. According to reports GNYHA donated $942,000 to a New York Democratic Party account supporting Governor Hochul's campaign. Additionally, analysis of campaign finance records show Fidelis Care's Political Action Committee contributed $69,700—the maximum allowable amount—to her campaign. Executives from Centers Health Care and Medical Answering Services have collectively donated more than $150,000.

The Trial Lawyers association gives its fare share of money to political campaigns as well however, including to the Grieving Families Act’s Sponsor State Senator Brad Hoylman-Sigal. According to Board of Elections records, Hoylman-Sigal has received at least $136,000 from law firms, legal interests, and super PACs linked to the New York State Trial Lawyers Association since taking office in 2012. Nearly half of this money has come within the last three years.

Additionally, since 2017, the New York State Democratic Assembly Campaign Committee and the The New York State Democratic Senate Campaign Committee have jointly received over $1.7 million dollars from the same sources. The State Democratic and Republican Senate Campaign Committees have jointly received over $1.2 million dollars from these PACs and interests as well.

Keri says the political gamesmanship means nothing to her. She sent certified letters and videos to the governor begging her to sign the bill and received no reply. The mother is blunt in her assessment. “The Governor had the chance to fix this, but she chose not to,” she says. “And she wouldn’t meet with us before making her decision.”

Dan echoes this frustration. “These same insurance companies operate in states where this law is in place. They’ve adjusted just fine. The only reason they fight this is because they don’t want to be held accountable. And Hochul is letting them get away with it.”

The McManus family and their supporters believe the governor’s pattern of vetoing the bill—timing it during the holiday season each year to avoid public scrutiny—is a sign of bad faith.

The McManuses have become reluctant advocates, sharing their painful story in hopes of compelling change. Their advocacy work is emotionally draining, but Keri believes it’s necessary. “It’s hard to put yourself out there when you’re talking about the worst thing that’s ever happened to you,” she says. “But if we don’t, nothing will change.”

For Dan, the fight has also been a way to honor Micah’s memory. “We’re farmers,” he says. “We build things, we grow things. This is just another kind of work—work that we never wanted to do, but work that has to be done.”