The Pollinators Pavilion: A High-Tech Habitat And Artistic Lab For Solitary Bees

"We need to turn our thinking about artificial intelligence away from human interest and entertainment and to the earth.”

"We need to turn our thinking about artificial intelligence away from human interest and entertainment and to the earth.”

A rendering of the soon-to-be-completed Pollinators Pavilion

The decline in bee populations and the effect it is having on the ecosystem is a crisis of immense scale but, for most, it is a problem difficult to see and even more complicated to internalize. In addition, researchers have spent the vast majority of their resources studying the plight of agriculturally useful honeybees while little is still known about the behavior or advantageous potential of solitary bees, the stingerless species responsible for as much as 70 percent of global non-agricultural pollination.

Right now, in Livingston, New York, a technologically innovative installation called the Pollinators Pavilion is being constructed to house, and study the nesting behavior of, solitary bees. Despite the project’s scientific complexity, the unique asthetic presence of the Pavilion manages to make an arresting and unified statement about these little-understood pollinators, their value, and how our relationship with them can be reimagined.

Recalling the shape of a bee’s compound eye, the Pollinators Pavilion was designed by architect Ariane Lourie Harrison and the project is being curated and coordinated by celebrated local artist and founding director of The Frank Institute at CR10, Francine Hunter McGivern. The Pavilion is being constructed at CR10 in Germantown but will soon be erected on a rise in the hemp fields of Hudson Hemp at Old Mud Creek Farm in Livingston. The research farm is owned by Abby Rockefeller and run by Ben Dobson, an innovator in the practice of regenerative farming. In time for next year's solitary bee nesting season, Dobson intends to plant crops of medicinal herbs, flowers and other plants around the instilation to attract the 20-plus varieties of solitary bees native to the region.

“The essence of this idea to create a field station was instigated by the collapse of honeybee hives and thinking about how we have another native resource (solitary bees) not being harnessed, simply because we don’t have as much research,” Harrison said. “The curved grid of nesting sites allows us to study the specific preferences of different species of bees in a way that’s never been done before.”

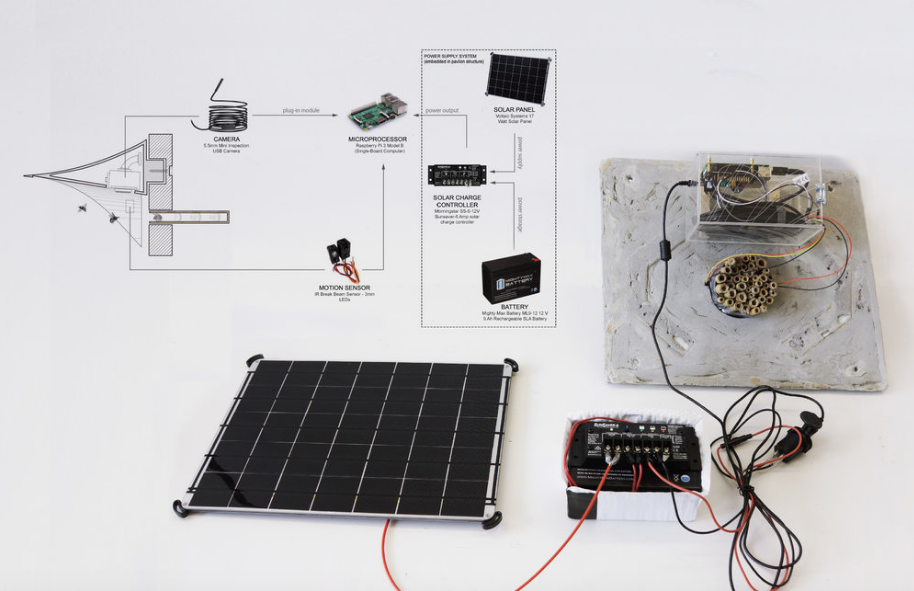

The Pollinators Pavilion provides inhabitation for 4,000 solitary bees in a structure of more than 300 cast concrete panels, fabricated at the Brooklyn Navy Yard workshop by project partner Ductal. The pointed form of each panel serves as both a rain canopy and a storage space for a solar-powered, tech-award-winning monitoring platform. Motion sensors at the base of the canopy, when triggered by movement, prompt a tiny endoscopic camera to photograph the insect. The images harvested by each panel feed into a database of a machine-learning system that seeks to identify the species without trapping or killing the bees.

“The monitoring system gives the Pollinators Pavilion its program as a new type field station,” said Harrison, who is also the coordinator of the Masters of Science programs in Architecture at Pratt Institute’s Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design. “As an educator, I am interested in new models of design research that intersect with and contribute to scientific research.”

The machine-learning database is designed to teach itself to identify and catalog individual bee species and their activity through advanced artificial intelligence. Working with Dr. Jerome Rozen, Curator Emeritus, Apoidea Collection at the American Museum of Natural History and Dr. Kevin Matteson, Director of Graduate Programs for Social and Ecological Change, Miami University, Ohio, the Pavilion has the ability to monitor these elusive bees at close range, using non-invasive methods, and promises to contribute significantly to solitary bee research.

“We hope to automate insect identification, see how many eggs hatch and which species proliferate in a system like this,” said Harrison. “There’s an increasing awareness that you can use these AI systems to monitor the earth.”

While the Pavilion will not be able to utalize its full capabilities until the beginning of next spring’s growing cycle and the bee’s nesting season, the completion of its construction will be celebrated at a soft opening at the farm Sunday, Aug. 11 at 3 p.m.

At CR10, where the Pavilion is currently coming together, McGivern sees huge potential for her nonprofit art space to connect directly with the Pavilion for future research, education and art installations. She said she's excited to use the data, visuals and sound recordings for artistic reinterpretation.

“The farm provides the right context for the Pavilion,” said Dobson, CEO of Hudson Hemp and General Manager of Old Mud Creek Farm. “It’s true art but it’s also advanced engineering, advanced science, and advanced architecture, designed to create a new vision of how we humans can relate to nature. The Pollinators Pavilion is a beautiful showcase that fits into our goal to rebuild the nature on this farm. This is an artistic statement about what can happen in a farming system like this.”

The Central research question of Harrison’s architecture firm, Harrison Atelier, is: “How can we build for more than one species?” She said they are attempting to challenge the preconceived notion of human-centric architecture and want to create a larger role for architecture in environmental activism.

“As a species, we should become aware of how little we know about the world around us,” said Harrison “There’s no going back. We have to accept the population density of our world. I’m actually optimistic about the way new technologies can solve these problems. We need to turn our thinking about artificial intelligence away from human interest and entertainment and to the earth.”