The Rural We: John Frederick Walker

The Litchfield County author and artist is included in an exhibition at Craven Contemporary in Kent, Conn.

The Litchfield County author and artist is included in an exhibition at Craven Contemporary in Kent, Conn.

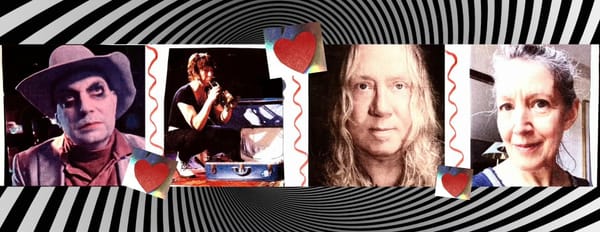

John Frederick Walker photo by Kat Manning

Litchfield County resident John Frederick Walker is as talented an author as he is an artist. He has written two books on natural history: “A Certain Curve of Horn,” about Angola’s giant sable antelope and “Ivory’s Ghosts: The White Gold of History and the Fate of Elephants.” His writing has also appeared in publications including The Washington Post, National Geographic News, and World Policy Journal. Walker’s art is represented in the Yale Art Gallery, the Brooklyn Museum, and the National Gallery. His work has been exhibited in solo and group shows nationally, and currently can be seen at Craven Contemporary in Kent, Conn. in the group show “New Nudes,” on view until mid-January, 2020. Walker and his wife, journalist and author Elin McCoy, have lived in Connecticut since 1985.

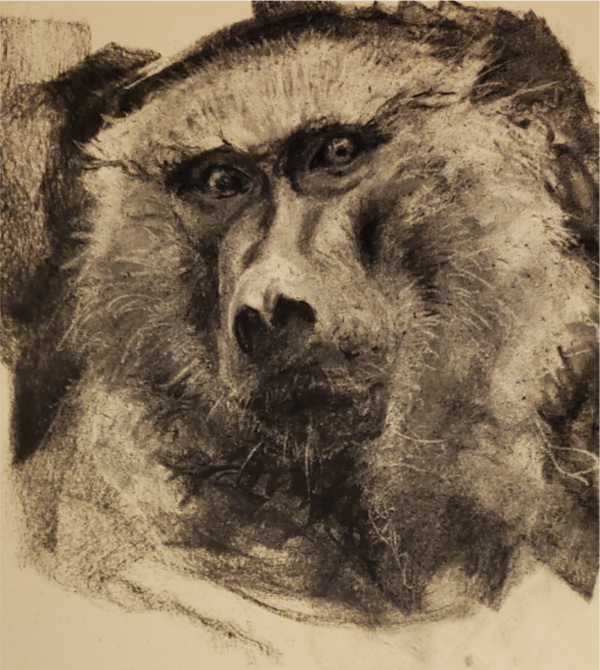

Andrew Craven and I first met at his former, pocket-sized gallery. He’s a collector at heart with a very sharp eye for relationships between the work of various artists. He’s a natural curator and puts on really unusual group shows, mini surveys of themes that interest him. Currently, artists are doing a lot more with the human figure than what’s traditionally shown on museum walls. His “New Nudes” idea — artists who treat the male and female body in new ways — means showing women artists who are reclaiming the female body, women painting women and men, men depicting men and so on. I have eight pieces in the show, and am delighted with the dialogue all the artists in the show are having with each other. To name just one, I find Mickalene Thomas’s collages of African American women a major rethink of black female beauty.

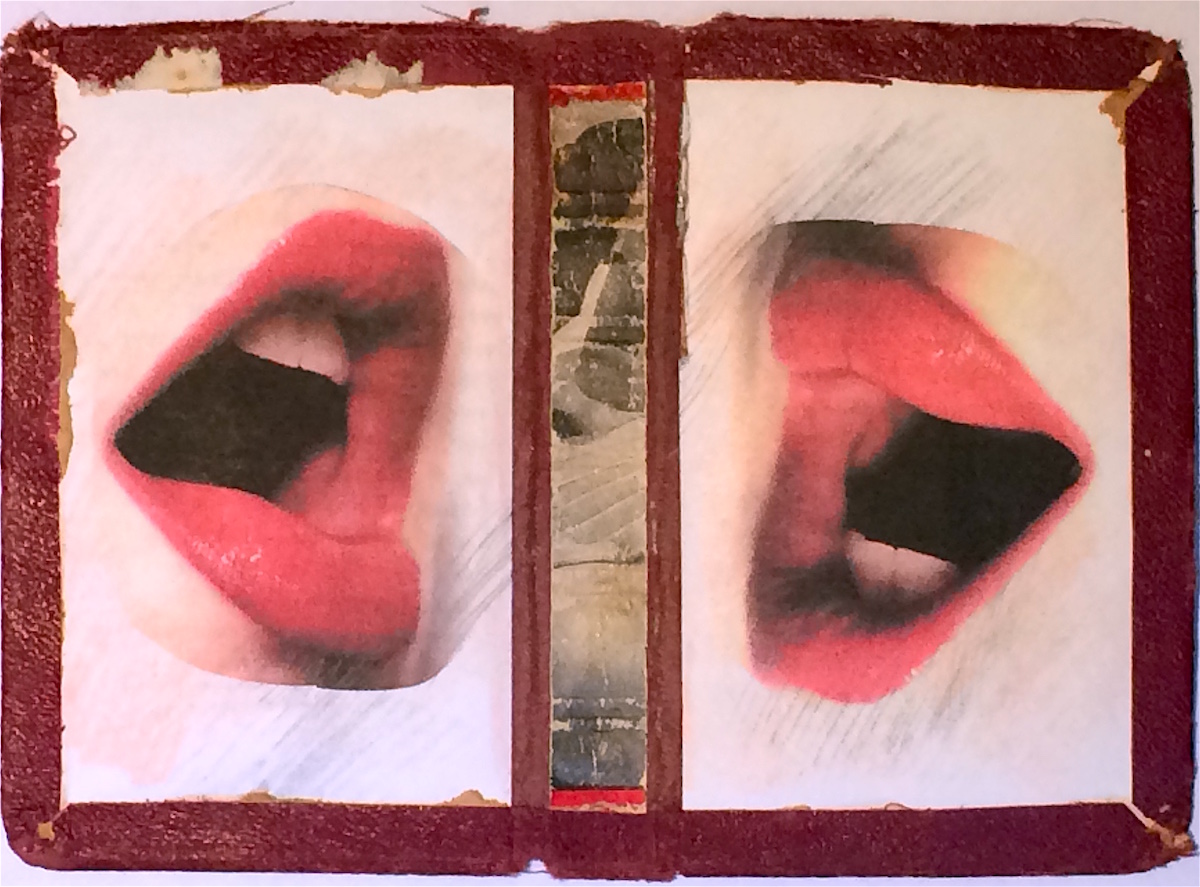

My own angle on the nude is the book. I’ve been making art all my life, with a lot of emphasis on minimalism and geometric works, and now do a lot with the book form. About 20 years ago I started scribbling on discarded journals and damaged books, wanting to capture the moment when a book is opened and reveals a fragment of what’s between its covers.

When viewers look at a locked open book, they know it used to contain content, and that triggers free association. They start reading it as if the content were there, even though they have no idea what was there. Many find an exposed, splayed book downright suggestive, finding sexual overtones even in ones that are abstract. I use the book is a framing device so you can see the subject and step back and consider it. One of my works in the show, “Three Graces,” uses an altered book with collage elements from an old manual of figure drawing which used a technical approach to de-eroticize the subject. But today these women arranged on graphed pages seem to be asking, “How do I measure up?”

Another piece of mine is “Susanna Ignoring the Elders,” based on the biblical story that’s a frequent subject in Western art. My version is an update in which Susanna could care less about what the elders think. It revisits their sexual hypocrisy as they stare across the pages at an image from an exhibitionist site of someone who seems to be saying, “Here I am, and I don’t care what you think.”