The Rural We: Madeleine Segall-Marx

The Hyde Park sculptor is inviting the public to her barn to view her 10-year, antiwar art project.

The Hyde Park sculptor is inviting the public to her barn to view her 10-year, antiwar art project.

Madeleine Segall-Marx has received more than 40 awards for sculpture, including ten Medals of Honor and the 2006 Dutchess County Executive's Art Award to an Individual Artist. She has completed three public works in New York City — in Greenwich Village for the Dept. of Parks and for Stuyvesant High School. She served as a board member and then as president of the National Association of Women Artists, the oldest and largest organization for professional fine artists who are women, where she initiated partnerships with the First Amendment Center, the National Coalition Against Censorship, the Feminist Majority, UNIFEM, and the New York Women's Agenda. On Sunday, Oct. 13 and Thursday, Oct. 17, the gallery Womenswork.Art will offer tours of WaveCrest in Hyde Park NY, the barn/studio and home of Segall-Marx and her sculptor husband. It’s a chance to experience Segall-Marx’s "The Singing Bowl: Voices of the Enemy,” her 10-year, antiwar visual art project, with the artist present. Based on the premise that “The enemy is one whose story we have not heard,” Segall-Marx has collected 25 personal stories from people caught in armed conflict. Each story, or voice, is represented by a visual artwork. Reservations can be made here.

My husband and I have been longtime SoHo residents but we’ve been spending more and more time in Hyde Park. We’ve been here for 33 years. We’re both sculptors and worked in bronze, so in the early days we’d go every other year to Italy to make work, then sell the work and use the money to make more work.

Once I hit midlife and my kids were sort of grown, I had the urge to make something that said something instead of just making objects. I’m very thrilled with form, color and material and that satisfies me, but I had an urge to say something. It took a while for me to figure out what I wanted to work on. I came across an article after 9/11 about the compassionate listening movement. The woman who started it was a Quaker. She was this little old lady who talked to everybody; she’d talk to these crazy world leaders, like Gaddafi.

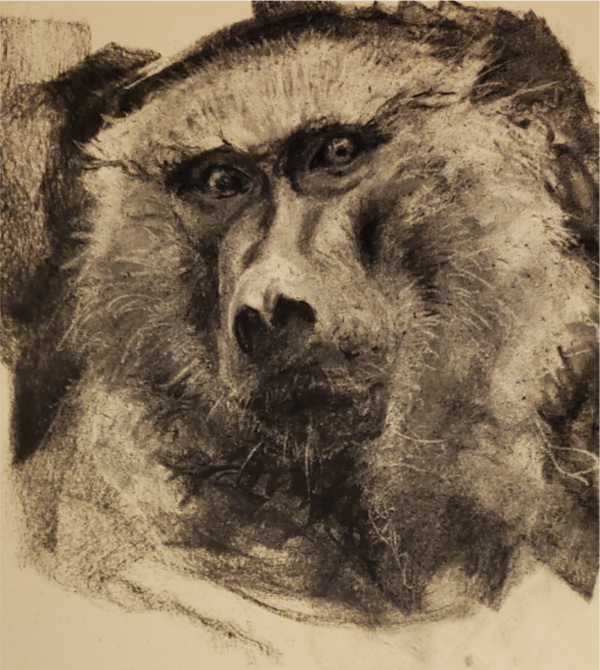

The idea had been knocking around in my mind, and for me that was a way to avoid war — listening. It’s crazy to shoot at someone who also brushes his teeth in the morning and smiles when his baby smiles. I crafted a project using visual art and personal stories from people who live or have lived in armed conflict. I had to tie the stories to something that people could see, and I thought of the most universal thing — food.

The project is not really about food, it’s just a device. When I got a story from a culture, then I took a recipe from that culture, and something from the recipe went into the artwork. Only three pieces have actual food in them: grain (kasha), peanut shells and rice. They still survive in my barn, somehow. It enables the viewer to play with the work a little bit more. When it’s set up as an exhibition, you can’t read it all, some stories are 25 pages long. They’re in the book, but they’re not all there on the wall. So explaining what I did and having them find the food engages them more. I was originally going to call it "A Random Feast," because the stories are quite different from each other in tone. Then I noticed that singing bowl tones sound like a lot of voices coming together.

I was planning on taking 2 years for the project; it took me 11. I really didn’t know where it would bring me, it was a journey. If I got a story from somewhere I wasn’t familiar with, like Russia and Chechnya, or Cambodia, I felt I had to read a couple of books before I got an idea of what to create. Friends helped me find stories. I have been in involved in an international human rights youth camp in Rhinebeck, and I got more than half of the stories through their connections. I got to know people and make friends, especially from Iraq and Nepal. I went to Nepal, it’s a poor community in a poor country, so that’s saying a lot. They had feasts and we went around to meetings with the heads of different villages, and the head was always a woman.

The guy who gave me a story from Iraq was a young filmmaker in his 30s and 2006-7 was a really dangerous time there. I knew he was in a lot of danger, and he asked me for help to get him out. I went to some lawyers to try to get him a visa, but Bush wasn’t letting in a single Iraqi, so I sent some money so they could go out of the country. He took actors, performers and artists and they went to Damascus because Jordan and Egypt had filled their quotas and weren’t taking any more Iraqis. Assad, at that time, was the good guy. I spent a month in Damascus and it was an eyeful how people live in tenuous situations. And they were not even the most tenuous, they had money, and they didn’t live in tents.

The project is 25 mostly large pieces. When I finished I put out the word across the country and got some interest from small museums, but it was so expensive to crate and move them, so now they are in the barn. As a place to visit, it’s an eyeful and it’s worth getting in your car and coming over. I can do a half hour tour or a five-hour tour on just the project itself: Who these people are, how I got the story. We’ll spend about an hour in the barn; I really need to describe what I’m doing beforehand, and then I can be there to describe why I did what I did. We have 5 acres, and we’re 2 sculptors, so there’s lots of other work around. Lately I’ve been collecting Hopi Indian kachina dolls, and I’ve got a collection that will knock your socks off.

I have a public work in Rhinebeck on the front lawn of Northern Dutchess Hospital which was inspired by my mom’s passing. She spent time in the hospital, and I thought that if I could create something new that could stay in the community, it would lessen my loss. She liked that idea. It’s a mythical creature, a newborn dragon, about 4x4 feet that went up in 2015. It has an Iraqi name. At the time, I was talking to a young Iraqi who was in hiding in Baghdad because his brother was a translator for the US Army. We spoke almost every day for about a year. He told me about a very Iraqi phrase that you say when there is a catastrophe. It that means “in it is something good.” Something has opened up so that something good could happen.