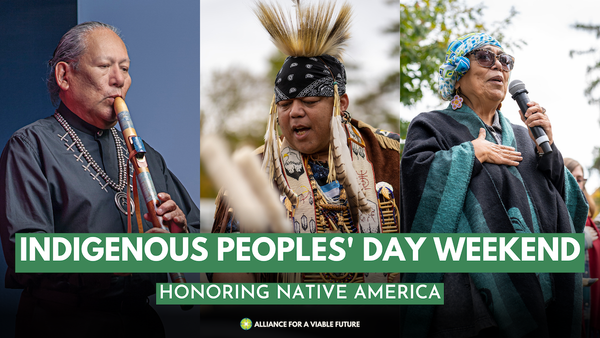

Tribal Nations Return To The Berkshires For Indigenous People’s Day Weekend

You're invited to a ceremonial concert and walk, and to meet representatives from the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans.

You're invited to a ceremonial concert and walk, and to meet representatives from the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans.

Photos courtesy Alliance for a Viable Future

Go to a live performance at a local performing arts space and you’ll likely hear the director offer a land acknowledgement. If you’ve been listening, you know that we live on the tribal land of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, who were forced in the 1830s to leave their native land. In a series of moves west, they eventually settled in Wisconsin, where the now-Stockbridge-Munsee Community is located on a reservation in the northeastern part of the state. That acknowledgement can bring us closer to the indigenous people who were the first to live on this land.

But here’s something that’s more tangible: Go to an event of the Berkshires’ celebration of Indigenous People’s Day Weekend, Oct. 6-9, in Great Barrington. Fifteen tribal nations, including the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans, will join a celebration of Native American culture on that weekend. On Friday, Oct. 6, the 2nd Annual “Honoring Native Americans” at the Mahaiwe will feature R. Carlos Nakai, the world’s premier performer of the Native American flute. Shawn Stevens, a celebrated Mohican storyteller, will open the program with stories of his people and a welcoming song. Cheryl Fairbanks, Esq., of the Tlingit-Tsimshian tribe in Alaska, who works in the area of Indian law as an attorney and on the tribal court of appeals, will talk about peacemaking in tribal communities.

Shawn Stevens, an enrolled member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans, an artist and musician, will perform and speak during Indigenous People's Day Weekend.

On Monday, Oct. 9, the community is invited to the family-friendly Indigenous People’s Day Ceremonial Walk on Main Street in Great Barrington. Starting at Giggle Park behind Town Hall at noon, it will honor the ancestral homelands of the Mohican people. Following introductions by the local and visiting indigenous council, community members can take a handful of tobacco and put it in a communal bowl while making a prayer. A walk up and down the sidewalks of Main Street will be followed by a stroll to the Housatonic River, where a memorial at Railroad Street in the past noted the spot where the Mohican people were forced to leave. There, walkers will make a prayer for the health of the river. Last year’s Ceremonial Walk drew hundreds of people.

These events are organized by Alliance for a Viable Future (AVF), founded by Lev Natan in 2018 “to focus on the collective healing process needed in our country but particularly here in order for us to have a viable future,” he says. AVF was the first organizer of Indigenous People’s Day in Great Barrington in 2020. Other goals include supporting climate solutions with like-minded organizations throughout the Northeast, and coordinating events for Indigenous People’s Day in every town and city throughout the northeast. AVF’s newest venture is the Mohican Homecoming Project, which offers fellowships for the Wisconsin Stockbridge Band of Mohican-Munsee individuals who wish to return to their ancestral homeland and build leadership skills to bring back to their community.

Last year was the first time AVF sponsored a delegation of Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians known as the "People of the water that are never still" to visit their ancestral homeland. For many, this was the first time that they visited the lands of their ancestors.

“The group, supported by other trial organizations and allies, planted a cedar tree at Kripalu with prayers and offerings,” recounts Natan. “Tears were shed.”

While many of the ceremonies and speeches are emotionally moving, it’s not all serious. At the walk on Sunday, kids — symbolically leading us into the future — get to stand in the front holding the sign. “It’s touching, fun, and chaotic,” says Natan.

The Mohican Delegation traveling from Wisconsin will be joined by tribal nations returning from last year, including Jake Singer, medicine man and sundance chief from the Dne Navajo Nation and others from the Tuscororo, Mohegan, Tiano, Ramapough Lenape, and Chicasaw nations.

“It’s particularly significant to have these ceremonies be public,” Natan says, “because Native Americans had not been allowed to practice their religion throughout most of the last century.”