Vincent Valdez Confronts American Amnesia in Powerful Opening at MASS MoCA

Valdez delivers one of the most important artistic statements on American identity ever, in North Adams.

Valdez delivers one of the most important artistic statements on American identity ever, in North Adams.

Vincent Valdez, So Long, Mary Ann, 2019, oil on canvas, 63 x 96 inches, Collection of Mike Healy and Tim Walsh, Santa Barbara, CA, on view at MASS MoCA

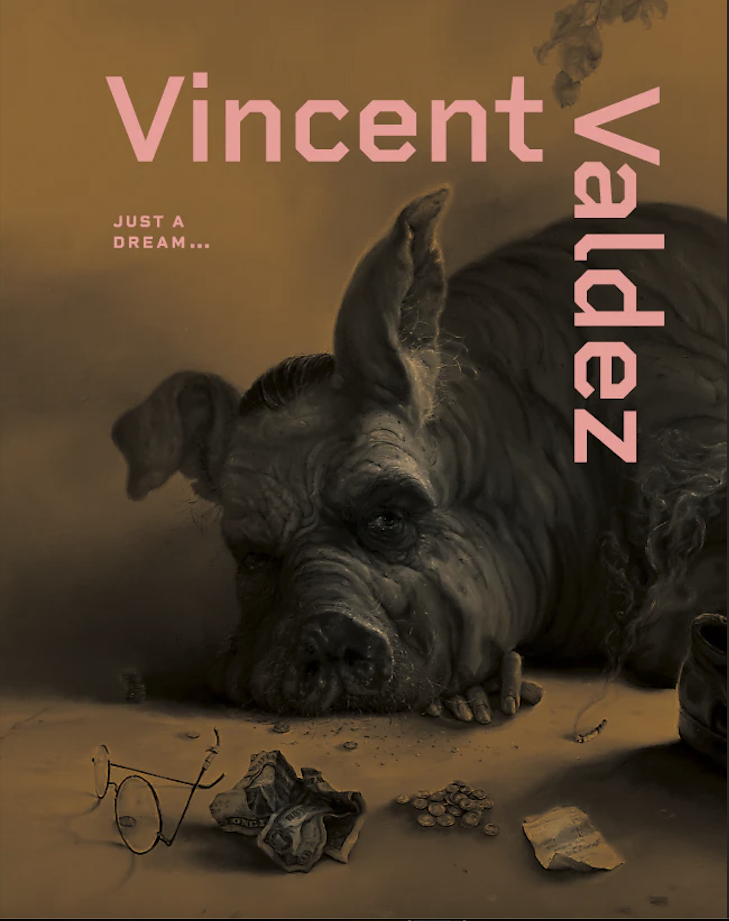

“It’s weird how when you see something scary, sometimes it makes you want to look more,” says a small boy to his father as they wander through the newest major exhibition at MASS MoCA in North Adams. His gentle words hung like an epigraph above “Just a Dream…,” the expansive retrospective of Los Angeles and Houston-based artist Vincent Valdez. Visceral, political, and brutally beautiful, the show spans nearly all of Valdez’s work to date—an urgent, unflinching body of art that confronts the American psyche with clarity and care. The show is a challenge and a plea for peace that we dare not look away from.

The work reflects national trauma—lynchings, murder, the KKK and systemic cultural erasure—but while Valdez looks back in anger he moves forward with a splintered optimism. “The very thing that you despise and that you regret and that... tears you apart, is the thing that drives you with such a powerful spiritual force that... it becomes your guiding hand through life,” he says during a conversation at the museum with writer Hanif Abdurraqib and co-curator Denise Markonish, this past Sunday morning.

Artist Vincent Valdez Discusses his early work, displayed in flat files in the gallery. Also pictured; Denise Markonish, co-curator.

The duality at the heart of Valdez’s work—the coexistence of violence and endurance—is one he connects to what he calls America’s “resiliency towards truth.” “Americans continue to remain so painfully trapped between myth and reality, past versus present,” he says. “Out of this denial of history comes a social amnesia.” Yet even as the country willfully forgets its sins, he says, “many of us still find the strength, and the resiliency, and the means to continue dreaming for a better future.”

The tension—between rage and hope—anchored Sunday’s artist talk. “How much more effectively could I love the people in my orbit,” Abdurraqib asks, “if I did not instead have to spend time putting myself up against the machinery of empire?”

Valdez agrees. “That’s the machine that I see,” he says. “This invisible machine that just keeps rolling forward every day.” He says he is fueled, in his rebellious act of truthtelling, by observing daily life—“people making tortillas in the back, sweeping the streets, walking to school, carrying their kids, walking their dogs.” Painting, for him, is not about representation alone. “What the real pursuit is for me is, how do you paint a moment in time? How can I capture the tensions, the anxieties, the uncertainties, the power of standing together, the power of daydreaming?”

In It Was a Very Good Year (1987/1988), 2024, a monumental 40-foot diptych, Valdez juxtaposes Michael Jordan’s famous 1988 free-throw line dunk with Lt. Colonel Oliver North’s raised hand during the Iran-Contra hearings. “Both of these individuals, these iconic moments in American history... within power structures of entertainment and spectacle... all of this becomes a mirage, blurred into one sort of faded memory,” he says. “I was attempting to capture not the way that those moments felt for me, being 10, 11 years old—I was trying to depict something much deeper.”

Vincent Valdez, Kill the Pachuco Bastard!, 2001. Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches. Collection of Cheech Marin and The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture of the Riverside Art Museum, California.

Pulling forms and lighting cues as much from comic books as his classical training, there’s a distinctive graphic pop to the texture of Valdez’s work that enhances his technical mastery. It seems as though you could press into the sweating neck muscles of black-and-white portraits of boxers, or hold the plump hand of his grandmother. Valdez paints exquisite hands. In So Long, Mary Ann, a portrait of a heavily tattooed Latino man, the subject’s clasped hands at the bottom of the frame exude as much, if not more, pathos than his eyes.

Despite the emotional gravity of his subject matter, Valdez insists on building positive connections. “It’s amazing when you can find other human beings in the world that share your language,” he says to Abdurraqib. “Because in moments like this, it can feel like it’s a very rare—and rarer—thing.”

As Sunday’s talk drew to a close, both men spoke of legacy—not as glory, but as responsibility. “It is safe to say that my work resonates like an alarm that rings nonstop in my head,” Valdez wrote in a message Markonish read aloud. “I must depict what I witness. This is my call to action. To get up and speak up.”

“Just a Dream…” is more than an exhibition. It’s a syllabus, an essential text for all those who pine for a more perfect union. MASS MoCA has done this region a great service by bringing Valdez here, so he can be witnessed and, most importantly remembered.

Vincent Valdez: Just a Dream… is co-organized by Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) and Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA).