Watch MASS MoCA Resident Artist Randi Malkin Steinberger Reimagine Lost Memories

The artist is in. Steinberger's process of creating is on display, as she builds her exhibition on site durring open hours.

The artist is in. Steinberger's process of creating is on display, as she builds her exhibition on site durring open hours.

Randi Malkin Steinberger in her Venice California Studio

- Olivia FougeirolFor artist Randi Malkin Steinberger, her current residency at MASS MoCA (on view now through June 29) isn't just a chance to create—it was an opportunity to recreate. Installed in a raw, light-filled space more commonly used for the giant former factory complex’s summer beer garden, Steinberger has transformed the handsome industrial room into a living collage of artistically enhanced found images titled “The Archive of Lost Memories,” an ever-evolving expression of how we collect, preserve, and forget.

“I purposely chose a space that isn’t directly connected to the museum,” Steinberger explains. “It hasn’t been used for this purpose before. But it has a lot of windows and light, and a lot of my work needs light—natural light.”

Photo by Jon Verney, courtesy of MASS MoCA.

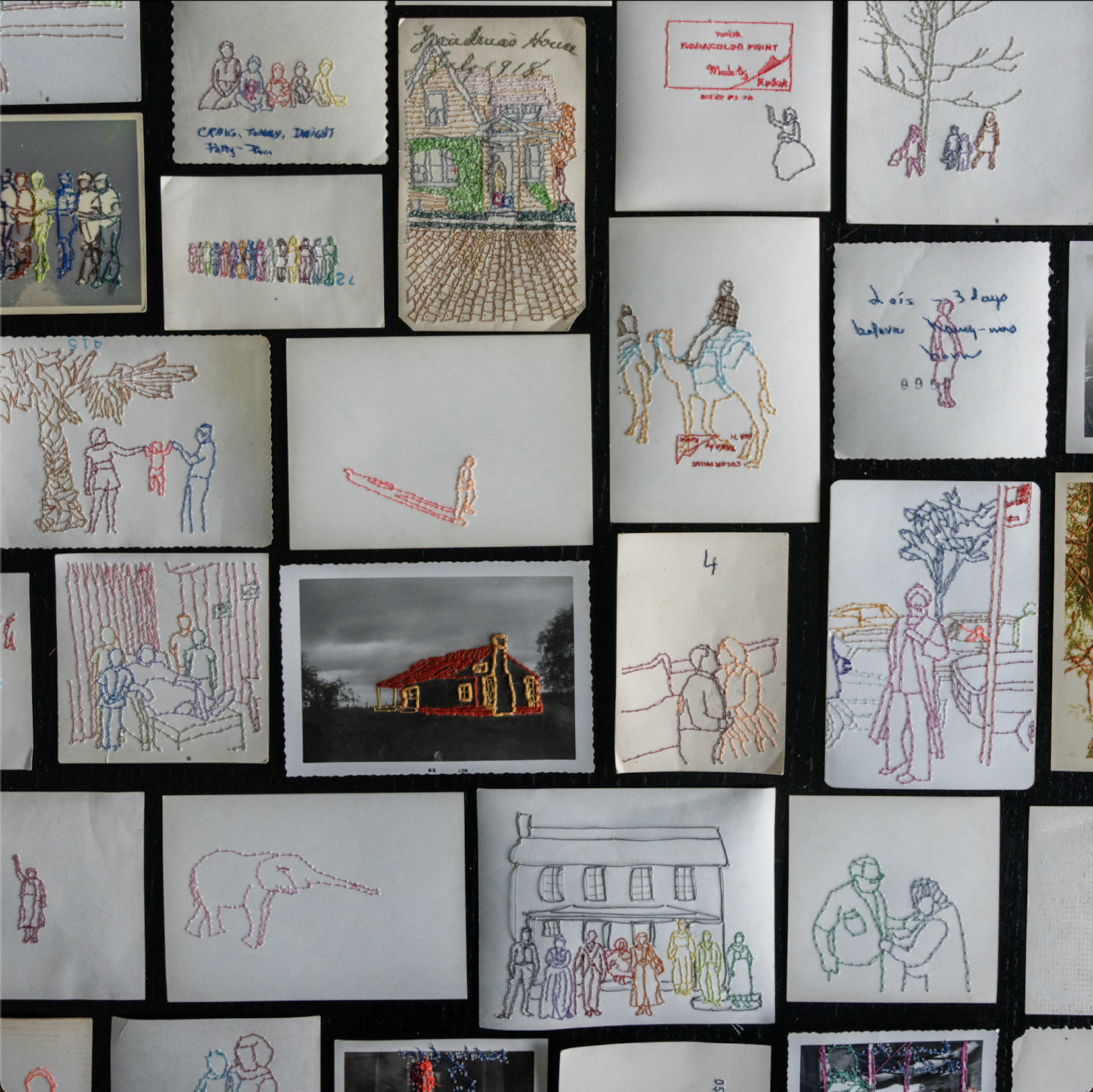

Inside the space, visitors encounter a curious assemblage of vintage photographs laced with mixed-media embellishments. Some have had the outlines of their figures stitched through with colorful thread and presented backwards, creating another ghostly level of thematic distance from the original moment captured long ago on film.

All is arranged on and around salvaged furniture, and hand-built display cases scavenged from MASS MoCA itself. “I thought it would be interesting to source all of the furniture and cases and chairs and work tables from the halls of the museum,” she says, “from things left over from factory days, to things from exhibitions in the past, to cases from the gift shop that weren’t being used. So in its own way, it’s kind of an archive of the building.”

The concept of archiving images and objects of personal, institutional, and forgotten significance is central to Steinberger’s project. The act of her process is also on display as she creates on site, during open hours. “What was proposed to me was to recreate my studio in Venice, California here,” she says. “My process is living and working with my art.”

Throughout the space, visitors can find delicate grids of photographs, some arranged into what she envisions as a kind of storyboard, others assembled by feeling, or pure visual resonance. The materials span decades: 20th-century family snapshots, vintage slides, and even 1980s Italian photobooth portraits that were ripped up and discarded, then reassembled by Steinberger by hand.

“I guess I always viewed it as grids,” she says of how she lays out images in interconnected ways. “Lots of things happen symmetrically, but nothing is perfect.”

That tension between order and spontaneity carries through her storytelling style, influenced by a practice early in her career of extracting stills from Super 8 films. “An individual image just doesn’t really do it for me,” she says. “It makes sense when there’s multiples put together.”

Photo by Jon Verney, courtesy of MASS MoCA.

Steinberger’s relationship with found photography is guided by instinct and self-imposed rules. She buys in bulk, only rarely making exceptions for one-off treasures like ancient tintypes. “The first thing that excites me is when I find photos that I feel like I would have taken myself,” she says. “In a way, I feel like I kind of view it like I took it—because I’m choosing it.”

This emotional proximity extends to the viewer as well. “It’s very accessible,” Steinberger says. “Even though they’re memories of people I don’t even know. I see the effect on visitors—triggering their own memories… or kids coming in who have never actually touched a real photograph.”

Some elements of her installation will remain in place after the residency ends in June, incorporated into the site’s repurposing as a summer beer garden. Panels of colored slides that act like stained glass will be left in the windows, and suspended sculptures will be moved higher, above head level. “The memories will live on and have a new life within the beer garden,” she says. “So that’s kind of fun.”

Though new to MASS MoCA, Steinberger had long hoped to work there. “I’ve always just really wanted to come,” she says. “I lived in Italy for 10 years, and a couple of my friends were assistants for Sol LeWitt, so I’ve always just known about the ‘temple to Sol’ here. I feel so lucky.”

The timing of her visit has also been meaningful. After 30 years in California, she’s inspired by the changing seasons. “I arrived here in winter and snow. if I look at the trees now—stare at them—I feel like I can see the leaves actually just popping out right in front of my eye,” she says.

For an artist who describes herself as shy, the experience of being “on view” has been unexpectedly rewarding. “It’s been a push for me to be able to do that,” she says. “But I really enjoyed talking to the people. It teaches me a lot.”

In the beginning, she jokes, “I felt like a zoo animal back here.” But she became more comfortable with it than she expected. “People aren’t coming back and staring. It’s more like they want to interact and talk. It’s been a pleasure.”

And ultimately, that interaction—that shared reflection on memory and connection, has added a powerful new level of intimacy to Steinberger’s work.