“Arlo Guthrie: Native Son” Exhibit Celebrates The First Family Of American Folk Music

If you’ve never been, now’s the time to get to the Guthrie Center to view the legendary Guthrie family's memorabilia.

If you’ve never been, now’s the time to get to the Guthrie Center to view the legendary Guthrie family's memorabilia.

I remember a few years back sitting down at a dinner party and telling the gathered that I’d just been lucky enough to meet the quintessential Berkshires celebrity. “You met Arlo!”, several of the gathered excitedly chimed in. I told them that no, it wasn’t Arlo. I was then asked if I’d met James Taylor. “Um, no,” I confessed. “Not James Taylor.”

Blank looks all around.

“Yo-Yo Ma,” I said. “I just met Yo-Yo Ma at Guido’s. Nice guy!”

Oh well, the chorus chimed in, nice guy Yo-Yo might be, but Arlo Guthrie is the quintessential Berkshires celebrity.

Chastened at the time for my misapprehension of the Berkshire celebrity pantheon, I nevertheless was recently delighted to be definitively corrected by “Arlo Guthrie: Native Son,” now on view at The Guthrie Center in Great Barrington. Curated by Arlo’s daughter Annie Guthrie, the exhibit is actually the first step in her vision to create a more extensive installation of memorabilia celebrating generations of the Guthries’ achievements as the first family of American folk music. Annie (herself a songwriter and performer) was Arlo’s road manager for decades, handling booking, travel arrangements, and other sundry and complex touring logistics. But with her father’s performing career now at an end, Annie has started to explore and catalogue the Arlo Guthrie Family Archive, now stored among three houses and a storage unit.

“I didn’t mean to become an expert on my father,” says Annie, “but I guess I’ve become one.” She grew up on the road with her three siblings (who in one year caused seven exasperated tutors to give up and quit, she remembers). As the young Guthries matured, they became part of the act. The charm of “Native Son” is the warm family feeling it evokes – and when you visit, it’s not impossible that you’ll encounter family members working to refurbish the building, the same former church where the two Thanksgiving dinners that couldn’t be beat immortalized in the song “Alice’s Restaurant” were served. There is also some cool memorabilia – props and stills of Arlo and Officer Obie – from the film version on view.

Certainly, there are artifacts that will give a charge to music fans – such as Arlo’s t-shirt and a bandmate’s ticket from the 1969 Woodstock festival. And anyone whose Thanksgiving would not be complete without listening to “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” (and perhaps some of the extrapolatory re-recordings Arlo produced over the years) will be thrilled to see not only an officer’s uniform donated by the Stockbridge Police Department, but also one of the 8x10 glossy pictures of the actual garbage Arlo and his pal tossed to the bottom of the 15-foot cliff. It’s in black and white and not color, some of you might be disappointed to find out.

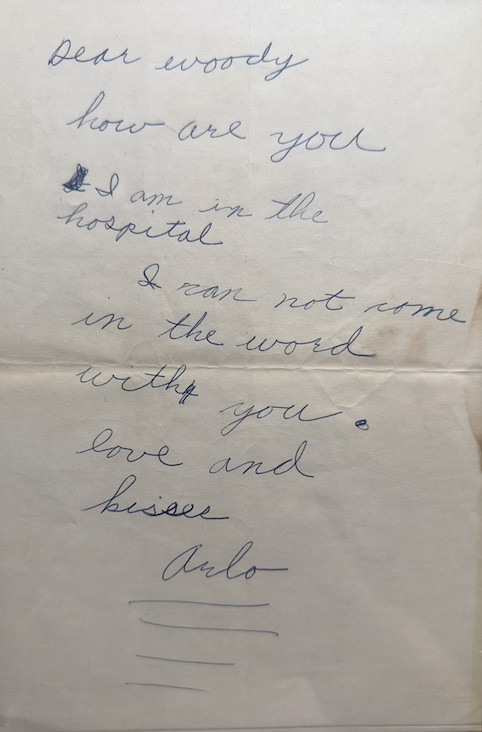

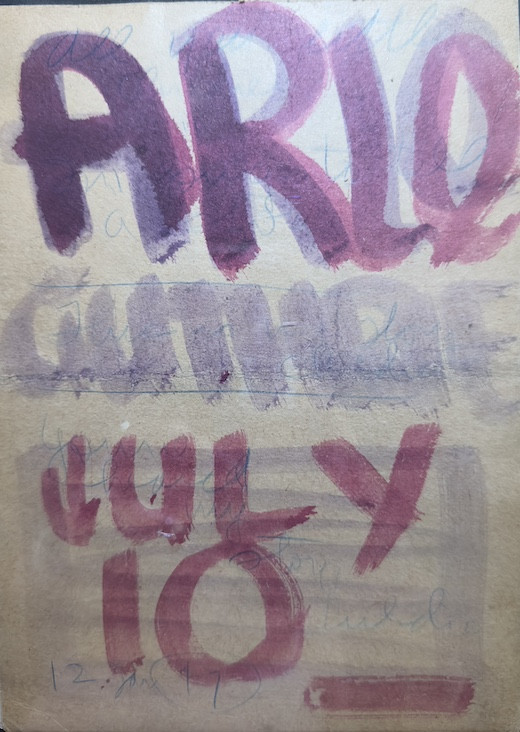

But what moved me the most were the intimate family treasures Annie Guthrie has shared. Her grandfather Woody was described in a 2019 NPR interview with Arlo’s sister Nora as “a deeply curious wanderer, who would go out for a pack of cigarettes and not come home for a week or two” – a characterization that does not exactly scream out “family man.” But in the “Native Son” exhibit, you can see an art booklet with a sweet notice hand-drawn by Woody announcing a birth on July 10, 1947. Next to it is a heartbreaking 1954 note from Arlo to his father, who was already hospitalized with Huntington’s Disease. “Dear Woody,” it says, in part. “How are you. I can not come in the word [sic] with you. Love and kisses, Arlo.” Next to his message is Arlo’s self-portrait of himself in tears.

“Native Son” also offers glimpses of a certain Guthrie family moxie that also seems to have endured over time. On view is a bar mitzvah message to Arlo from his maternal grandmother, the noted Yiddish poet Aliza Greenblatt – number 5 on the list instructs the young man to “do whatever possible today. You don’t know what tomorrow will bring.” One display case over is Arlo’s own list of house rules for his children from the mid-1980s that he has titled “The Law.” Among them:

When Dad is away, there will be no dancing on the tables

Never have fun on weekdays

Never say never.

Another sweet reminder of how Arlo and family sustain relationships is the copy of his 2004 children’s book Mooses Come Walking, illustrated by Alice Brock – remember Alice? Arlo wrote a song about Alice.

Overall, “Native Son” is a charming exhibit, whether or not you’re a folky or an Arlophile or even a Berkshirian. (Google tells me Berkshirite is not what you call people from the Berkshires – I am chastened again.) But I actually did get the chance to meet Arlo a few years back. He and I were standing together in a long line waiting for our prescriptions to be filled at the Walgreen’s on Elm Street in Pittsfield, an experience that feels like nothing so much as sitting on the Group W bench at the draft board building down on Whitehall Street in New York City. We talked about Thanksgiving and how I also make it a point to listen to his fall-of-the-Berlin Wall “I Can’t Help Falling in Love With You” story, and how, yes, the Metric System remains a scourge the world has yet to fully overcome (check out his 1987 performance of Pete Seeger’s “The Garden Song” if you don’t know what I’m talking about – you won’t be sorry).

What can I tell you? The quintessential Berkshire celebrity – nice guy!