Artist Proposes Suicide Prevention Signs After Uptick in Deaths at Hudson River Bridge

Rhinebeck Norm Magnusson drafts more hopeful and poetic suicide-prevention signs for the Kingston–Rhinecliff Bridge.

Rhinebeck Norm Magnusson drafts more hopeful and poetic suicide-prevention signs for the Kingston–Rhinecliff Bridge.

A rendering of a proposed sign by Norm Magnusson.

- Norm MagnussonEditor’s Note: This story discusses suicide. If you or someone you know is in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 to connect with the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, or visit 988lifeline.org/chat to talk with someone right now.

Suicide in the United States has been stubbornly high. After two decades of rising rates, deaths by suicide topped roughly 49,000 in 2023—a record high. That scale, a death every 11 minutes by the Centers for Disease Control’s count, is the national backdrop to tragedies closer to home. In the Hudson Valley, the Kingston–Rhinecliff Bridge has become the focus of grief and anxiety after a series of deaths by jumping. Nationally, such cases account for only a small percentage of suicides, but when they cluster around a single landmark, the place acquires an outsized, tragic weight.

Into this fraught space has stepped Rhinebeck-based multi-hyphenate creative Norm Magnusson. Known for his faux historical markers that parody the look of official roadside plaques, Magnusson has proposed something much more earnest: new suicide-prevention signs for the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge. Where existing placards read “You are not alone” or “Help is available,” Magnusson suggests messages that are more evocative and less easy to dismiss.

“They have these signs say, you are not alone or help is available,” Magnusson says. “And every time I saw the one, especially, ‘you’re not alone,’ I was like, bullshit. If I were really struggling with suicidal ideation and had sort of the mental infirmities that led me to that message, ‘you were not alone’ would just read as complete and total bullshit to me.”

A rendering of a proposed sign by Norm Magnusson.

Instead, he began drafting lines that carried what he calls “an element of hope” and a touch of poetry, like: You haven’t met all the people who will care about you. “It’s hard to call bullshit on that because, who knows?” he says.

Some of the wording reflects personal conversations. His sister, a retired psychiatric ER nurse in Albuquerque, once told him that if a person in crisis could just be persuaded to take a breath and step back, that pause could be lifesaving. Her advice surfaces directly in his draft: “Stop. Take a breath. Reach out for help.”

Magnusson has not subjected his phrases to full clinical review, though he has shared them with acquaintances in suicide-prevention work. He did circulate them to a local elected official a couple of years ago, and recently revived the proposal when a task force on bridge suicides was convened. He knows the chances are slim. “It’s a super long shot,” he admits. But he hopes the exercise might at least prod authorities to rethink their language. “Maybe they’ll come up with stuff and maybe it’ll be a lot nicer and better, more effective in the end than what I came up with.”

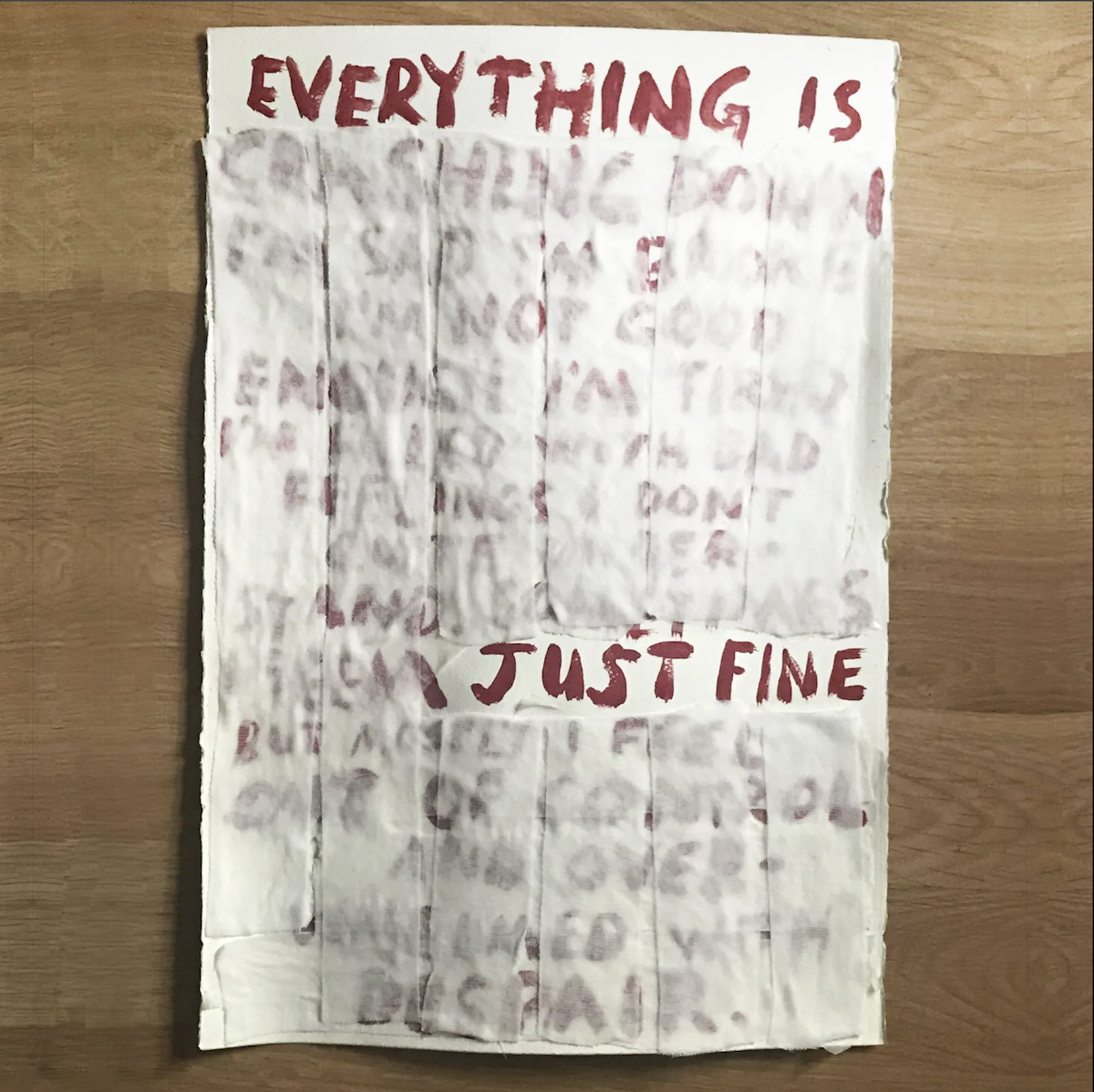

Norm Magnusson’s "Everything Is Just Fine," a mixed-media piece on men’s mental health, layers painted bandages over hidden phrases of despair to reveal how people often mask their true struggles.

The realities of bridge safety are sobering. Barriers are the most effective deterrent. When the Golden Gate Bridge finally installed stainless-steel nets in January 2024, suicides there dropped by nearly three-quarters. But barriers are expensive. Local estimates for a fence on the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge have run as high as $20 million—politically and fiscally daunting. “A fence is probably the most effective thing, right? It’s not going to be pretty, it’s going to be expensive,” Magnusson says. “Well, what price do you put on these lives? A fence would be great, but changing the verbiage on these signs is going to cost like five grand or something. It’s a very inexpensive and possibly positive fix.”

Magnusson’s proposal draws on decades of experience with language in public space. A professional copywriter since the early 1990s, he is perhaps best known in the art world for his “On This Site Stood” series, in which he cast aluminum signs in the official style of New York State historical markers but filled them with commentary on healthcare, climate change, and democracy. The works have appeared in museums and public installations from the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum to rest stops along I-75, sometimes fooling passersby into thinking they were state-sanctioned. They reveal his fascination with how public signage can shape collective memory and perception.

A rendering of a proposed sign by Norm Magnusson.

But the bridge project is different. “This seems more civic-minded than arts-minded to me,” he said. He admits it may not save everyone, but he hopes the new phrases might make someone pause. “Would different kinds of signs diminish the numbers of people jumping? That’s the hope,” Magnusson says. “Would these signs get people to stop and pause more than what’s there now? I feel really strongly that they would.”

For Magnusson, the project is less an artistic statement than a personal necessity. “It’s bad for me personally to not try to make things better when I see a way that they could be better,” he says. In that sense, the proposal is less quixotic than it first appears. Against a problem as vast and devastating as suicide, it is, quite literally, better to light one candle than curse the darkness.

If you or someone you know is struggling, immediate help is available. Call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, or visit 988lifeline.org for chat options and resources. Locally, county mental-health departments and crisis centers can provide referrals and emergency support.