“Marilyn Uncovered” — The Bert Stern Family Collection At Sohn Fine Art

The gallery debuts the family collection of Bert Stern's last photographs of Marilyn Monroe prior to her death.

The gallery debuts the family collection of Bert Stern's last photographs of Marilyn Monroe prior to her death.

"People had a habit of looking at me as if I were some kind of mirror instead of a person."

--Marilyn Monroe

Artists have been captivated by Marilyn Monroe's presence since U.S. Army photographer David Conover took a picture of an 18-year-old Norma Jeane Mortenson while on assignment in a California munitions factory in 1944. Artworks inspired by Monroe seek to make sense of her complicated inner life, but prints of her sourced directly from film — a magical emulsion that captures reflected or enveloping light, leaving behind a shadow of space once occupied — are as close as one can get to seeing her in the flesh.

Such is the case with the exhibition “Marilyn Uncovered,” on view at Sohn Fine Art in Lenox, Massachusetts through September 30. Nestled quietly in the back of the gallery are 14 matted and framed prints of Monroe taken by acclaimed artist Bert Stern (1929-2013) who, like Conover, was once a photographer in the U.S. Army.

It’s difficult to look at these images without utterly devastating hindsight. Captured over the course of two weekends in mid-1962 at the Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles, the work was to become a multi-page fashion spread in Vogue magazine. Tragically, the actress died six weeks later, August 4, from a barbiturate overdose at her home in Brentwood, and the feature, which had already been sent to press, was canceled, re-edited, and released that September as a memorial.

"Crucifix II," 1962. Archival pigment print, edition 6/10, 24" x 24". Signed by artist. Image courtesy Sohn Fine Art.

Stern began his career as a commercial photographer before landing contracts like the one with Vogue, which allowed him to pitch the Monroe shoot to the art director. “He was actually in Rome, photographing Elizabeth Taylor on the set of ‘Cleopatra,’ when he got the got the call from Vogue [greenlighting the project],” says Trista Stern Wright, Stern’s eldest daughter.

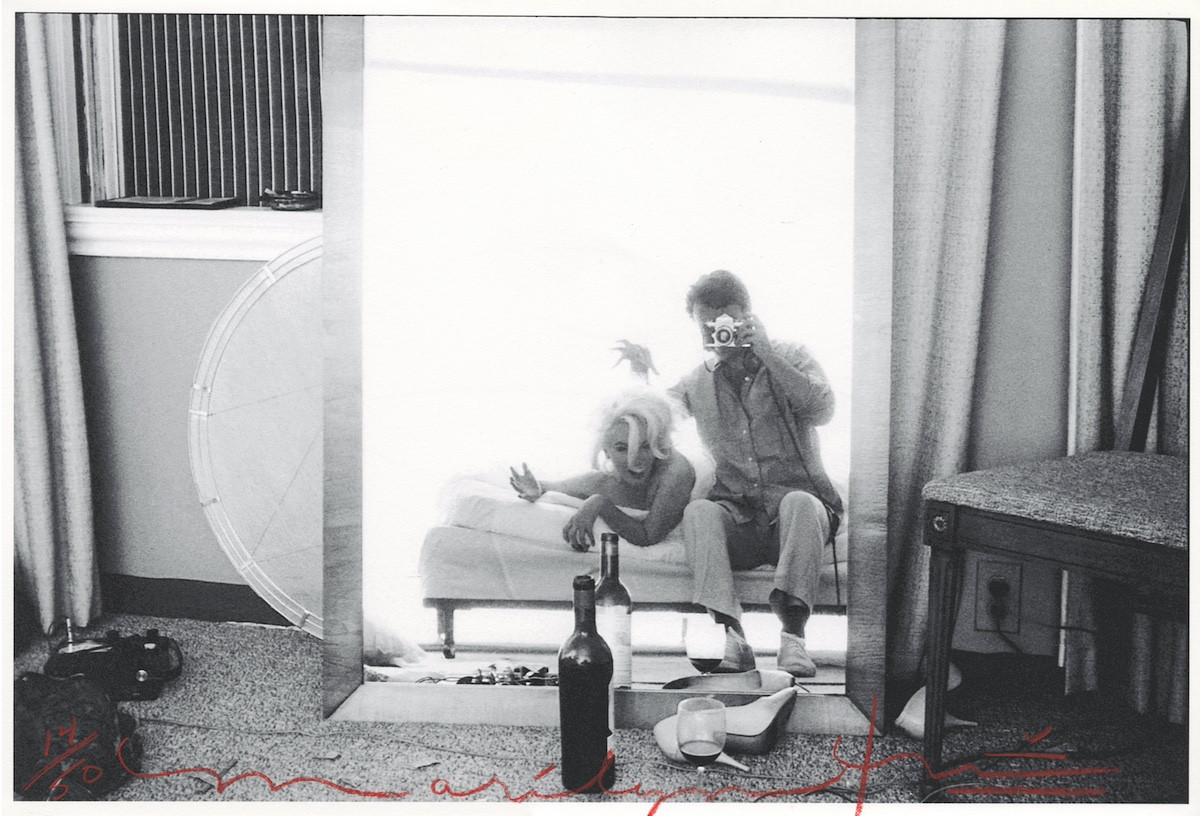

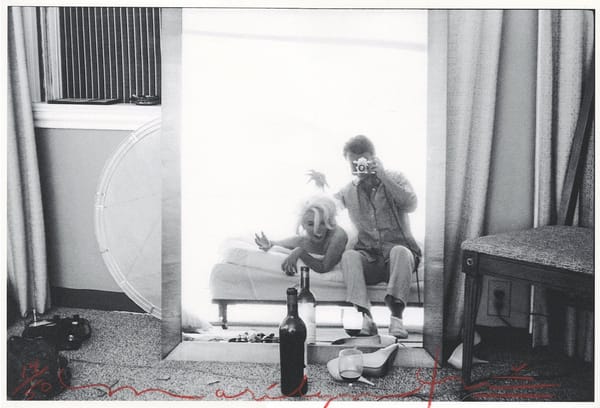

Just three years Monroe’s junior, Stern had a young family at the time of the infamous shoot. One photograph in the exhibition, “Marilyn and Bert in the Mirror,” is a reflected portrait of the artist and subject on a bed, backlit by a mountain of sunlight. Strewn around the mirror are pieces of photography gear and cables, high heels, a wine bottle, and a half empty glass of red wine; Monroe dangles hers over the bedside, laughing. It’s easy to imagine these two thirty-somethings discussing relationships, children (or Monroe’s brutal pregnancy losses), childhood, fame, age, and art once the alcohol calmed both their nerves.

“He liked to leave the details because he wanted to reveal her as a person,” explains Wright of the candid image. “When she got in from of the camera, she was just so unbelievable — she embodied the [experience] so fully.”

Only two images in the exhibition feature a fully clothed Monroe wearing what look like designer dresses — expected for a fashion editorial. The rest depict her clutching roses, sheer scarves, bed sheets, and beaded necklaces to her otherwise bare chest, skirting the line between vulnerability and exploitation. Known throughout her life as a sex symbol, Monroe was not one to shy away from exposing her body before a camera. She was a pin-up model in the 1940s, posed nude for photographer Tom Kelley to pay the bills, leveraged sexpot roles to propel her film career, and returned to nudity in the filming and still photography for her last, unfinished movie, "Something's Got to Give."

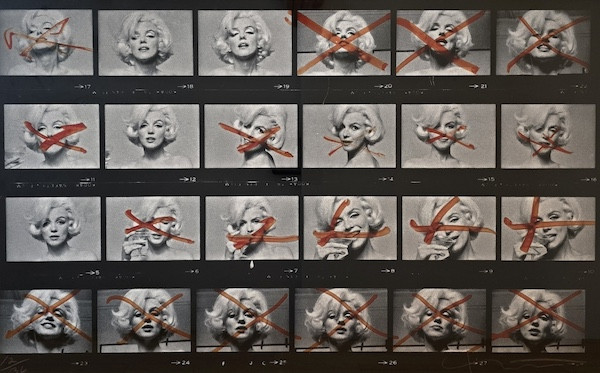

"All Marilyn's Markings," 1962. Archival pigment print, edition 12/36, 28.5" x 39" framed. Signed by artist. Image courtesy Sohn Fine Art.

As she honed her negotiating skills with studio executives, Monroe also exerted more influence over her printed image. She would review photographers’ proof sheets, or contact sheets, and cross out images she didn’t like with a red marker. One of Stern’s contact sheets — a series of 24 thumbnail portraits that animate Monroe like Muybridge’s galloping horse — is featured here. Another print, titled “Crucifix II,” is perhaps the most arresting image in the exhibition. Monroe’s own markings create a second veiled layer, inadvertently evoking violence, trauma, and martyrdom.

“Crucifix II” and other images in “Marilyn Uncovered” may be familiar to devoted Monroe fans. Stern published hundreds of previously unseen photographs from the shoot, known as “The Last Sitting,” in book form in 1982, and the complete set of over 2,500 photographs in 2000. But these grainy, mesmerizing prints have a power and resonance that reproductions simply do not.

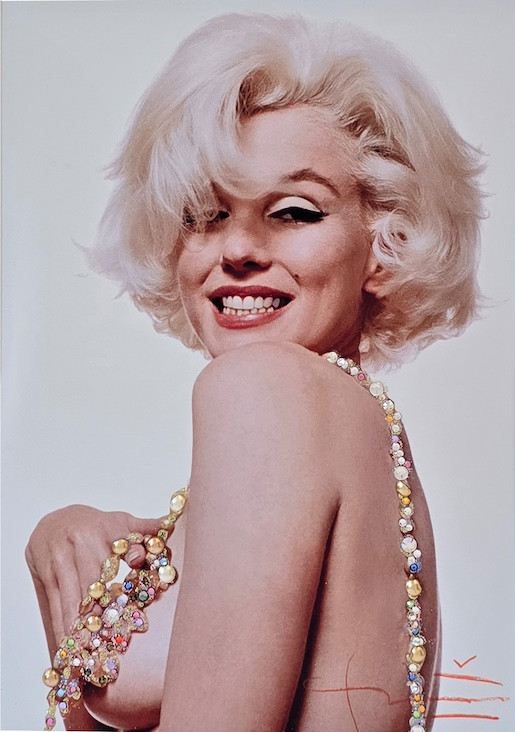

Additionally, half the works are embellished with crystals and jewels, a collaboration with Stern’s two former assistants, Lisa and Lynette Lavender. While more iconic than intimate, these “jewel-toned” prints, each a one-of-a-kind work of art, capture yet another facet of Monroe’s persona: the starlet.

“He definitely tried to put his own specific stamp on things,” says Wright of her father’s creative legacy. “He made [his photographs] unique and special.”

A reception celebrating “Marilyn Uncovered” as well as the summer exhibition “Alchemy of Light,” a four-person show of two roster artists and two invited artists whose work creates magic through light, chemicals, and metals, will be held at Sohn Fine Art on Saturday, August 17 from 4-7 p.m.